by Jonathon Catlin

This is Part II of Jonathon Catlin’s interview with Federico Marcon about his latest book, Fascism: History of a Word (University of Chicago Press, 2025). Following their discussion in Part I about the semantic origins and transformations of the term, Marcon’s semiotics-inspired methodology, and the importance of examining this concept on a global scale, this part explores the book’s relation to the “Fascism Debate” of recent years, its debts to Frankfurt School critical theory and other forms of historical semantics, and ultimately the role of conceptual historians in furnishing their readers with a conceptual and epistemological toolkit to historicize and clarify contemporary discourse for themselves.

Jonathon Catlin: I appreciated the way you position your book vis-a-vis the so-called “fascism debate” that engaged many historians following the resurgence of global far-right populism in the last decade. As I explored on this blog and elsewhere years ago, shortly after Donald Trump’s rise in American politics, liberals like Timothy Snyder, Ruth Ben-Ghiat, and Federico Finchelstein readily employed a generic concept of fascism while intellectuals on the left like Corey Robin, Samuel Moyn, and Daniel Bessner criticized this usage because it served to exoticize Trump and distract from the continuities his movement represented with America’s domestic radical right. You stay out of this normative dispute, instead clarifying what is at stake in such contestations of the term. You ultimately sympathize with Theodor W. Adorno, who claimed in 1959, “I consider the survival of National Socialism within democracy to be potentially more menacing than the survival of fascist tendencies against democracy” (90). As he put it elsewhere, “one might refer to the fascist movements as the wounds, the scars of a democracy that, to this day, has not yet lived up to its own concept” (9). You similarly argue that across all these historical eras the term’s “usage as an ideal type, widespread since the postwar era, hides the parasitic dependency that its historical forms had on the institutions of liberal democracy” (22). After all, both Mussolini and Hitler did not seize power in violent coups but rather were handed it by elites and parliamentary maneuvers; and both claimed to be enacting “true” democracy by doing away with ineffective parliamentarism (see Müller, Contesting Democracy, 116–17). I’d like to push you a bit to elaborate on your stance in the fascism debate. How would you describe this inherent potential for fascism within democracy?

Federico Marcon: In a sense, this book is my response to the “Fascism debate.” As I said before, what bothered me the most from that debate was its rushed nature, suggesting that the situation was perceived to be so urgent that it could not afford any rigorous, self-reflexive analysis of the terms of the debate itself. So, even though I found some of the interventions quite compelling—Bessner in particular, but also Herzog and Geroulanos, Robin, your own, and many others—the use of “fascism” in that debate was in its most generic fashion. The debate, that is, was conceptually regulated by the adequacy of the given definition of “fascism” (or of the checklist of features that “fascism” was conceived of containing) with the resurgence of authoritarian postures today. I saw at least two problems in that reasoning. The first is that the adoption of “fascism” as an appropriate interpretant of the present political situation aimed less at developing a sharp analysis of the causes and dynamics of authoritarianism within today’s socioeconomic circumstances than at emphasizing the crisis of democratic institutions and ideals. That is, its illocutionary use aimed at signaling an impending danger, so that “fascism” operated largely as a “scare word” in the Orwellian sense of simply pointing to anything that liberal democracy is not. Second, in most interventions “fascism” operated as an abstraction, as an ideal type, largely following the definitions given by Griffith, Payne and other proponents of the “fascist minimum” mentioned before. So, the political, cultural, ideological or institutional aspects of Italian Fascism and German National Socialism were mentioned more as illustrations of what the abstract political form “fascism” was assumed to be, rather than as straightforward comparisons, which would imply more thorough examinations of the similarities and dissimilarities of the societies and circumstances that favored the emergence of those regimes.

What I think is the risk of this application of “fascism” as an abstract political type, even if not necessarily in the reductive mode of the “fascist minimum,” is its hypostatization as a discrete and recognizable political form that is distinct from and antagonistic to the liberal institutions it confronts. What a proper comparative analysis would show, however, is that Italian Fascism and German National Socialism grew within and developed into regimes that remained largely parasitical upon the preexisting institutions of liberal democracy; they never dismantled the mode of capitalist production, market economy, and private property; and they utilized, by refunctioning them, even the terminology and legal apparatuses of previous liberal regimes. In the book I borrow (and modify) Benedetto Croce’s metaphor of fascism as disease (an unfortunate metaphor) to insist that Mussolini’s and Hitler’s regimes were not invading pathogens (as the hypostatization of the ideal-type “fascism” suggests) but rather neoplastic diseases. We cannot legitimately say that there wasn’t the time to create their own institutions, since Mussolini had uncontested power for twenty years! The revolution Mussolini advocated was a mere simulacrum, as its regime strengthened the preexisting hierarchical divisions of Italian society and the unequal distribution of wealth. That is why for me the Adorno’s quote that you mentioned above is so important in drawing our attention to the always present potential for the institutions of liberal, capitalist democracies to become authoritarian and illiberal. The use of “fascism” as a distinct political form, to me, hides and hinders the recognition of the authoritarian potential inherent in liberal capitalist democracies, which can become authoritarian in many different ways, some of which completely distinct from the historical precedent of Fascism and Nazism because responding to different historical, cultural, and social circumstances.

JC: Staying with our friend Teddie Adorno, your book takes an oblique approach to one of the central social and political questions of the twentieth century: “people’s voluntary abdication of the modern emancipatory ideals of freedom, equality, and solidarity” (6). But rather than addressing this problem through social theory, like Adorno, your “book conceives of a political dilemma of twentieth-century history in epistemological terms” (7). Can you say more about how your aim of breaking what Adorno called the “spell” (Bann) of fascism relates to the general social dilemmas that preoccupied antifascist thinkers like the Frankfurt School and Antonio Gramsci?

FM: The book never directly tackles this issue, but it truly is the core question behind all research on interwar authoritarianism and its revamp today. Still, it remains on the horizon throughout the entire book, which rather investigates the heuristic affordances of the term “fascism,” which is the name conventionally given to that befuddling phenomenon of modernity. In a sense, the model reader that the book painstakingly builds step by step is one that takes upon themselves the burden of answering that dilemma. The book provides the reader with an analytical toolkit and with a thorough understanding of the semiosic and epistemological effects of the conceptual apparatus of that toolkit. I make this strategy of the book clear in the Preface, when I write that “I avoid the rhetoric of persuasion” (xiii).

This is the real utopian, untimely, and, if you want, naïve move of the entire project: i.e., its pedagogical approach. It intends, perhaps too subtly, to invite a framing of the entire project that places at its center a pedagogical goal: the accretion of the reader’s competence on how the system of signification works (the encyclopedia, as Eco called it, the structure and modifications of which are always and necessarily social) in mediating the mutual making of the mind, society, and the world. The history of the formation and consolidation of the semantic markers of “fascism” and the reconstruction of the historical circumstances that accompanied that semantic process aim at furnishing the reader with a conceptual and epistemological toolkit for them to tackle that question. That is what I learned from Adorno regarding breaking the “spell” (Bann) of concepts, and it is also a way to remain faithful to the Enlightenment project and its emancipatory mission, a common feature in Adorno’s philosophy, Umberto Eco’s semiotics, and Pablo Freire’s political pedagogy.

The book is certainly difficult in the sense that it demands a lot of its readers, yet it does not require any prior knowledge: all the technical jargon it uses and the philosophical conceptions it refers to are explained in the main text or in the footnotes. As a consequence of this approach, I imply what I think is the social condition of scholars today, and the relatively marginal role we play in today’s world. I address this only in the Conclusions chapter, when I propose “a new semiotic guerrilla” where the role of intellectuals is simply to help “take care of semiosis—of meaning making—and its proper functioning (…): to care for its capacity for truth-telling as well as its polysemic potential, universal accessibility, and effects in society and the world” (306).

JC: As someone working in the tradition of conceptual history inspired by Reinhart Koselleck, I want to ask you about two contrary impulses in your book that similarly shape my own work: critical dismantling, but also semantic reconstruction—in other words, disassembling and reassembling a given concept. On the one hand, you acknowledge the claim that through overuse, especially as a pejorative “‘boo’ word,” fascism has been “emptied by its semantic uses, which have consumed and exhausted it” (3). As a corrective, you write, “This book wants to regenerate the significance of ‘fascism’ by tearing apart the history of its usages and meanings and putting it back together with renewed analytical cogency” (3). Relatedly, you claim that fascism “operated as a historical agent” insofar as it mobilized fascists and antifascists (5), but you also warn of “the hypostatizing effect of concepts,” in which by positing fascism as an object of study the Cold War historians pursuing a generic concept of fascism succumbed to the “reifying effect” of assuming the existence of their object of inquiry (17). How do you balance these competing impulses, in order to recognize the agency of concepts but avoid the “spell”-like fallacy of hypostatizing them? Can one perhaps speak of a dialecticin your method of critique combined with semantic reconstruction?

FM: The history of ideas more semiotico that I propose in this book is not incompatible with conceptual history, but it wants to complement and expand some of its heuristic reach by placing at the center of its theoretical explorations the processes of consolidation (conventionalization) of the interpretants of words (Begriffe,in semiotics “sign-vehicles”) through acts of sign production and interpretation. These interpretants, the cultural units that sign-vehicles conventionally signify, are not natural, universal, or primitive in a Chomskian sense. Rather, the structured ensemble of denotative and connotative markers that constitutes them results from processes of conventionalization within a historical society. The organized system of signification of a culture, what Eco called “encyclopedia,” appears to be fixed and stable, but in truth it is given stability by communicative acts that repeat and reiterate the registered meanings (denotative and connotative) of the terms. That said, these markers are historically subjected to transformation and modification, resulting from changing social, political, and cultural circumstances that render the referential utilization of some key concepts less felicitous. Initially, new semantic markers form through new, unconventional, reformist, antagonistic, or aberrant semiosic use of terms. Most of these aberrant uses are lost and forgotten, but a few succeed in becoming conventionalized, and thus enter the encyclopedia, expanding the semantic structure of the cultural unit with new denotations and/or connotations.

In the case of new terms like “fascism” or of modification of others that in particular historical moments have played a pivotal role in social, intellectual, and cultural transformations (e.g., “revolution,” “subjective/objective,” “liberty,” “nature,” etc.), the consolidation of the new semantic markers takes time, during which denotations and connotations are unstable, they can quickly transform, they circulate only within small social groups, and they can be subjected to erasures, censorship, hybridizations, etc. Most new usages of terms are destined to disappear, but some succeed in entering the encyclopedia in virtue of their repetition and recurrence, or the acknowledgement of their referential usefulness. This is a very superficial and vague description of a complex mechanism, so I invite readers to go back to Fascism: A History of the Word or, even better, to Eco’s A Theory of Semiotics (1976). What in the book I call the disassembling or breaking apart of words is precisely the reconstruction of the historical processes of consolidation or disappearance of particular semantic markers; the aim is to prevent these meanings from becoming naturalized, taken as universal, and thus determining our knowledge of past phenomena and events. Begriffsgeschichte does this only partially. A conceptual history more semiotico like the one I try to do in my book offers clear analytical advantages (I list these on page 19): among these, it avoids the hypostatization of semantic structures (a sort of referential fallacy, Adorno’s “spell”) and does not rely on the naturalization of the semantic system (the question of universals or primitives), nor on the “intentional intervention of semantic demiurges (be they God, ‘great historical figures,’ or white male philosophers)” (ibid.), as I put it, tongue in cheek, in the book.

In the long run, what conventionalizes the semantic structure of our words is the total sum of semiosic acts within a historical community (that historically can be as small as a village or as large as the entire world, especially for those words, like “fascism,” that travelled globally), and conventionalization is simply the result of repetition, adhering to interpretive habits which that community perceived as having referential advantages. If I can again quote from the introduction, I’d only add that “in producing signs, communicating, producing and interpreting texts of various kind, we all contribute to reinforcing” the received semantic markers of terms and to “setting up the conditions for transforming the systems of signification” behind ideas or concepts that are deemed to have transformative potential in a particular historical moment. This is what I mean by the eventual reassembling of words (in this case, “fascism”) in order to have potentially felicitous effects in the world. And this is why I decided to end the book with the somewhat naïve expression that “the means of linguistic production must ultimately be collectively owned by all.” Our social duty as scholars, I believe, is to take good care of the proper, precise use of language, because it is through it that knowledge of and potential transformation of the world, the mind, and society occur.

JC: You write that your ultimate goal is semantic clarity about our world: “In a sense, the fight against fascism really begins with our emancipation from the spell of its language” (xiv). You do not see yourself as an interpretive judge, but rather as playing a small part in “the shared ownership of the means of linguistic production.” Because meanings “derive from the total sum of the collective interventions in communicative acts,” you “do not believe that one scholar can impose restrictions, limits, or legitimation on the way we use words.” Rather than prescribe or proscribe correct or incorrect uses of fascism, you more modestly lay out “the heuristic advantages and disadvantages as well as the political consequences of its use.” By contrast, I am sometimes frustrated by arguments like Jan-Werner Müller’s that “there can’t be such a thing as left-wing populism by definition” (93) because “populists are always antipluralist: populists claim that they, and only they, represent the people” (20) and similarly that there’s no such thing as “illiberal democracy” despite many people using these phrases in these ways. You suggest that we scholars don’t possess the authority to serve as normative language police in this way. What kind of interventions can and should we historians be making in our discursive contexts?

FM: I don’t think I can speak for “we historians,” but I can tell you what I believe our social responsibility is. Let me premise that with two methodological qualifications. First, what scholars can expect to achieve through their interventions depends on the sort of historical context they operate in. We are historical beings, and as historians I think we have the duty to historicize first and foremost us, our methodologies, our convictions, and our place within our society. Accordingly, it seems to me that we live in a historical moment where scholars’ voices are increasingly marginal, and where our work is constantly delegitimated. This is a huge question I can’t afford to tackle here in a few words. We must, at least, begin by acknowledging that, as intellectuals, we live in a dramatically different world from the one in which scholars that interrogated the social role of intellectuals like Antonio Gramsci, Theodor Adorno, Michel Foucault, even Pierre Bourdieu and probably Umberto Eco lived, and that our work has far less social traction than it used to have in the past. This is by no means an invitation to write like Dan Brown or like political agitators, or to abandon all and become a hermit or a cynical hedonist. Scholarly and agitational texts are semiotically different: they follow different scripts and different rhetorical strategies, and they are bound to different notions of truth-procedure. My book explicitly defends the right and duty of scholarly research. Second, whatever we think our role in society is (or should be), this must be congruent and coherent with the sort of society we would like to contribute to build: e.g., one cannot really criticize capitalism and then act as scholar only to maximize one’s marginal utility or one’s social and cultural capitals. There is no scholarly work, no matter how disinterested, that doesn’t have a surplus of political meaning. In the way we talk and describe social events of the past there are inevitably traces of what we believe society to be, simply because there is no natural way of organizing a society. This is why in chapter 12 I insist on the interpretive nature of historical knowledge, which can be contradictory while pursuing truth-procedures. And this is why I insist that we need to always disclose the theoretical guidelines we have followed in our argumentations.

Moving from these two premises, I believe that as a historian of ideas my responsibility is to help students and readers to acquire and understand the conceptual and theoretical means that guide my own research, so that they can follow, reconstruct, qualify, analyze, criticize, correct, or falsify the reasoning, evidential apparatus, and the claims I make. I have always loved José Ortega y Gasset’s maxim that “every time you teach, also teach to doubt what you teach.” My commitment to this idea of scholars’ role is congruent and coherent with my ideal of an emancipated society organized around the principles of freedom, equality, and solidarity. Intellectuals, as educators, should offer the toolkits and language for students and readers to understand the very process of knowledge production and its effect on us, on society, and on the world, so that they can use that understanding to become actively engaged in their own emancipation. I learned this from Freire and Gramsci, and Adorno and Eco gave me the theoretical instruments that have helped me at least try to live up to that ideal. I certainly tried to do it in this book.

Jonathon Catlin holds a Ph.D. from Princeton University and is a Postdoctoral Associate in the Humanities Center at the University of Rochester. He is currently writing a history of the concept of catastrophe in twentieth-century European thought. He has contributed to and edited for the JHI Blog since 2016. He is on X at @planetdenken and Bluesky at @joncatlin.bsky.social.

Edited by Jacob Saliba.

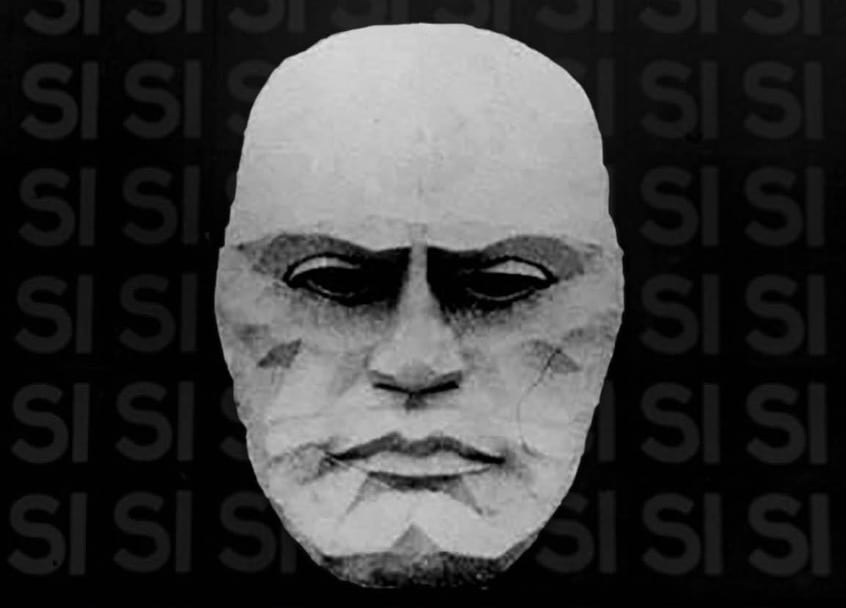

Featured image: Detail from the cover of Fascism: History of a Word, which shows Mussolini’s face on the facade of Palazzo Braschi in Rome, 1934.