2025 sees the 30th anniversary of the establishment of Historic England’s Register of Historic Battlefields. It lists 47 English battlefields from the Battle of Maldon in AD 991 to the Battle of Sedgemoor in 1685.

Eight battlefields from the intermittent period of civil war and rebellion between 1455 and 1487, known as the Wars of the Roses, are included on the Register:

Although these sites of conflict include some of the most recognisable names in English history, their history and what happened there is often obscured by later myths and legends.

The Victorians were the chief culprits here, often romanticising the battles and their landscapes. For example, the story that the Lancastrian queen, Margaret of Anjou, had a local blacksmith reverse the shoes on her horse to make good her escape from the Battle of Blore Heath originated in the 19th century and was popularised in Victorian history books.

Perhaps the most widely known and persistent myths relating to the battles of the Wars of the Roses are those that originated with the Tudors. For the dynasty that came to the English throne after the defeat and death of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, the wars held special significance.

They were an example of what happened when overambitious nobles, such as Richard, 3rd Duke of York, or his son, Richard III, took advantage of weak kings.

Henry VII, the first Tudor king, put an end to the civil wars by marrying Elizabeth of York (the daughter of Edward IV) and uniting the red rose of Lancaster and white rose of York.

The most influential Tudor myth-maker was, of course, William Shakespeare. His 3-part work covering the reign of Henry VI and his historical masterpiece, ‘Richard III’, presented a distorted Tudor view of the Wars of the Roses.

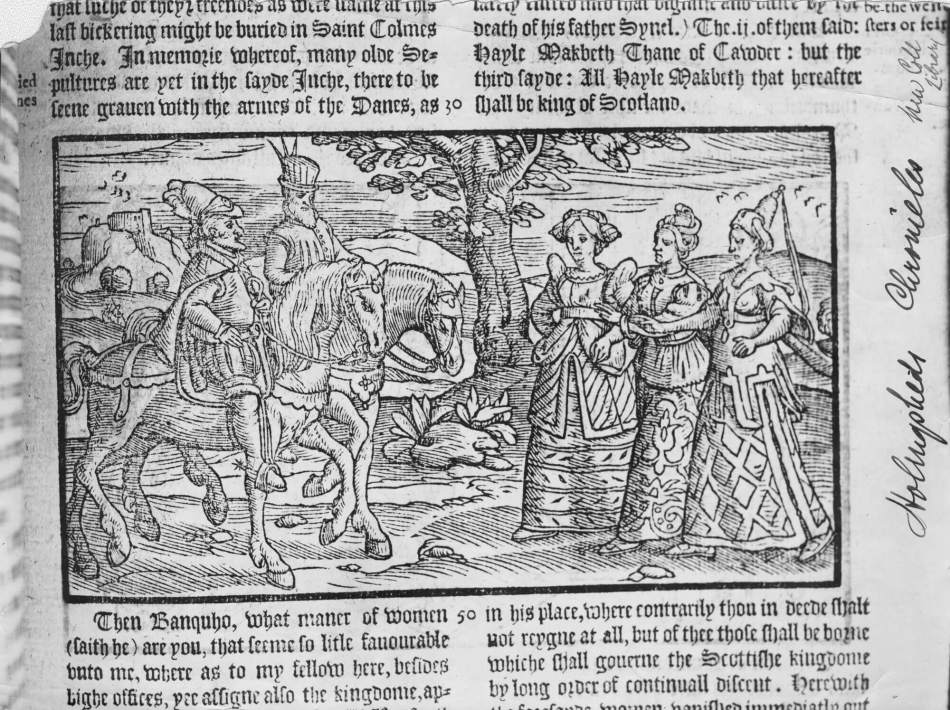

Shakespeare’s primary source was Raphael Holinshed’s chronicle, published in 1577. Shakespeare almost certainly knew and read an earlier chronicle, first published in 1548, by Edward Hall entitled ‘The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancastre and Yorke.’

Hall, in turn, used the work of the Italian historian Polydore Vergil, who began work on his ‘Anglica Historia’ in 1505 at the request of Henry VII. Together, these men embellished existing accounts and invented stories of the battles of the Wars of the Roses that still often dominate our understanding today.

One of the most persistent myths that runs throughout this Tudor history of the wars was the role given to Henry VI’s queen, Margaret of Anjou. Her enemies at the time portrayed her as the political leader of the Lancastrian party, but the Tudor writers took this one step further, assigning her a prominent role as a military commander.

Vergil wrote that she commanded the Lancastrian army at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460, where the Duke of York was killed. In fact, Margaret was in Scotland when the duke was captured and killed near the town. Vergil also suggests Margaret was in command of the Lancastrian forces at Tewkesbury, when in reality, she was sheltering in a nearby religious house.

From these earlier inventions, Shakespeare developed his characterisation of Margaret as a revengeful and tyrannical ‘She-Wolf.’

In terms of the current Registered Battlefields, no battle was as misrepresented by the Tudor historians as Towton. The Battle of Towton, fought on Palm Sunday, 29 March 1461, was the decisive battle of the first stage of the Wars of the Roses. It secured the throne for the young Yorkist king, Edward IV.

It is often acclaimed as the most significant and bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil, and it is typically portrayed as having taken place during a snowstorm. There is, however, a limited amount of contemporary evidence to support either of these claims. Both may be Tudor inventions or, at the least, embellishments of the facts.

The story that the Lancastrian archers shot their arrows into a blinding snowstorm and that the Yorkist commander, William, Lord Fauconberg, had cleverly placed his men just out of range originated in Edward Hall’s chronicle. Hall justified his claims about the respective armies’ size by claiming to have seen a muster roll.

Yet, if the Yorkist army was indeed 48,660 men strong, it would probably have been the largest army assembled by any Christian king in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Another myth that probably originated with Hall, and which was picked up by Shakespeare, was that of John, Lord Clifford. Hall explained how Clifford had murdered York’s son, the Earl of Rutland, in 1460 in revenge for the duke’s murder of his own father 6 years earlier at the Battle of St Albans. Clifford plays a prominent role in Hall’s account of Towton, which is not supported by contemporary sources.

In Shakespeare’s ‘Henry VI, Part 3’, the character ‘Bloody Clifford’ murders the innocent Rutland and the Duke of York before the Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III) defeats him at Towton. Shakespeare, we know, never let the facts get in the way of a good story, as Richard would have been only aged 8 (and with his mother in the Low Countries) when the Battle of Towton was fought.

Shakespeare, of course, saved some of his most notable misrepresentations of the battles of the Wars of the Roses for his favourite villain, Richard III. Richard fought bravely at both the battles of Barnet, where he was injured, and Tewkesbury, commanding portions of the victorious Yorkist armies for his brother, Edward IV.

In his writing, Shakespeare ignores Richard’s role at Barnet but has him join with his brothers in stabbing Margaret of Anjou’s son, Prince Edward, to death at Tewkesbury, before rushing off to the Tower of London to murder Henry VI.

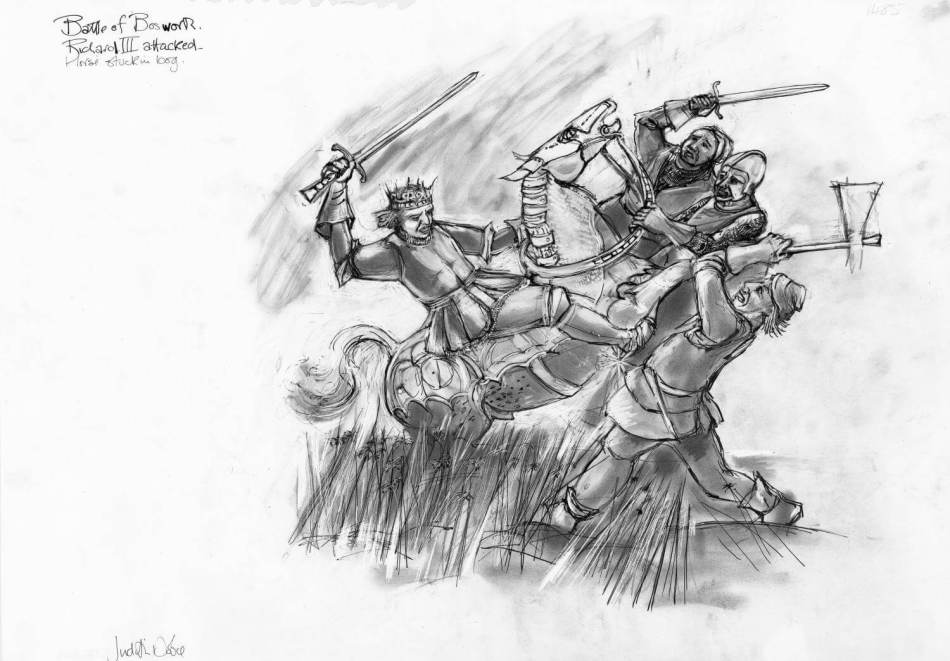

Richard’s death at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 was the climax of Shakespeare’s play about the last Plantagenet king. Even Richard’s fiercest enemies, such as Polydore Vergil, agreed that Richard died fighting ‘manfully, in the thicket press of his enemies.’

Shakespeare’s Richard, however, is a coward, crying “A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse” more than once as he tries to escape the battlefield. Rather than being surrounded and cut down, Richard is killed by his nemesis, Henry of Richmond, the future Henry VII, in single combat.

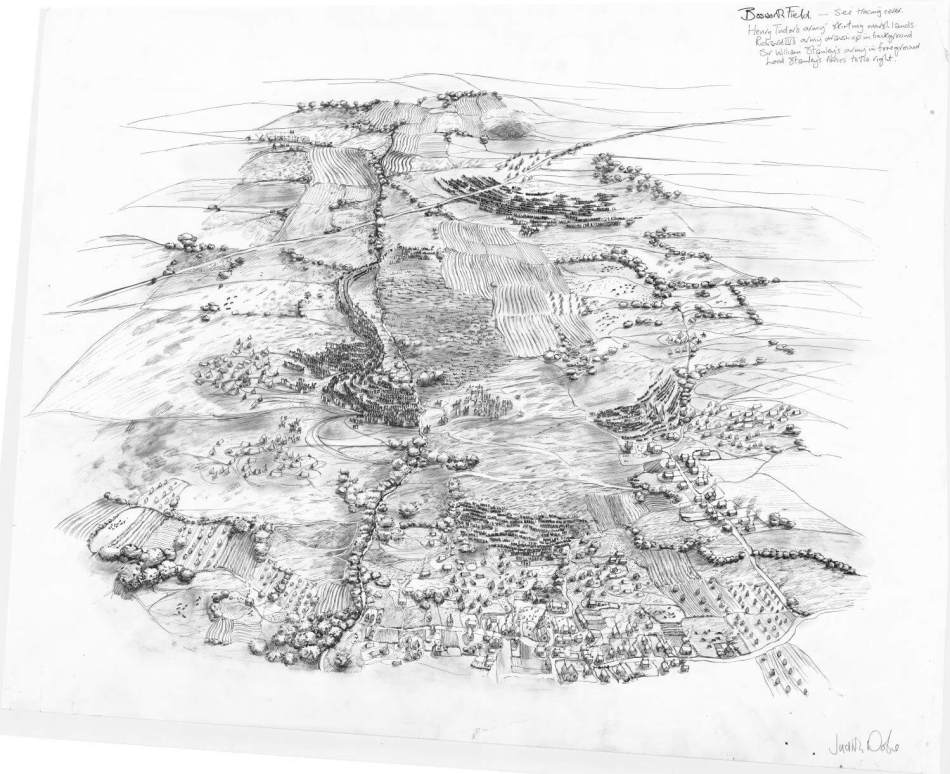

Recent research by Mike Jones, Glenn Foard, Anne Curry, and others has debunked the Tudor myth of Bosworth. Richard’s actions in the battle are now recognised as those of a brave and chivalric knight staking his kingship and reputation on the ‘wager of battle.’

But why did Shakespeare write about Richard III in such a negative way? Shakespeare wrote many of his history plays in the 1590s, during the reign of Elizabeth I, the granddaughter of Henry VII. Also, some of Shakespeare’s important patrons had family connections to the Tudors, such as Ferdinando Stanley, a direct descendant of Thomas Stanley, who famously switched allegiance to Henry at the Battle of Bosworth. Therefore, it would have been surprising for him to portray Richard in a positive light and risk political repercussions.

The historic battlefields of the Wars of the Roses are now recognised as important sites of memory and myth. Battlefield archaeology can tell us a great deal about how battles may have been fought, but it is equally important to understand how these landscapes were memorialised.

The Battlefields Trust’s Wars of the Roses Memorial Database is a crowd-sourced, open-access database that captures the memorials, stories, and myths associated with the Registered Battlefields of the Wars of the Roses and other sites linked to the 15th-century civil wars.

The rich and complex history of these landscapes is as much about myth and memory as it is about recovering the facts of what happened over 5 centuries ago.

Written by Dr David Grummitt, historian at The Open University and member of the advisory panel for The Battlefields Trust.

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Register of Historic Battlefields in England, The Battlefields Trust is offering opportunities in September 2025 to explore England’s battlefields, including those involved in the Wars of the Roses at Northampton, Edgcote and Tewkesbury, in a series of free, expert-led walks. Details of how to book a ticket for the Big Battlefield Walks Weekends can be found here.

Discover your historic local heritage

Hidden local histories are all around us. Find a place near you on the Local Heritage Hub.

Further reading