by Jeffrey Kluger

Named by Time Magazine as one of the most anticipated books of fall 2025, Gemini by Jeffrey Kluger reveals the thrilling, untold story of the pioneering Gemini program that was instrumental in getting Americans on the moon. Read on for a featured, introductory excerpt!

Like every man who had ever orbited the earth before them, Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin knew their lives depended on their retrorockets. The very purpose of the rockets was in the retro part of their name—to accelerate their spacecraft not forward but, in effect, backward, slowing the ship down and bleeding off speed, which was essential if Lovell and Aldrin were going to live another day after the ninety-four hours they’d already spent in space.

Orbiting the earth, after all, is effectively an act of falling around the earth—flying high enough and fast enough that even as your spacecraft speeds forward and downward, the surface of the planet curves away from you, meaning that while you fall and fall and fall and fall, you never, ever reach the ground. Like the moon, you become a stable satellite of the earth, staying aloft long after your water and air and power give out. So while Lovell and Aldrin had happily gone to space aboard their Gemini 12 spacecraft—the last of the Gemini program’s ten manned missions—they very much looked forward to turning their ship rump forward, firing their four retro-rocket motors, and subtracting enough speed from their 17,500-mile-per-hour velocity that gravity would have its way with them and they would begin a controlled plunge through the atmosphere.

On the afternoon of November 15, 1966, the men began the homecoming maneuver, facing their ship backward and bracing for the lifesaving engine burn.

“We are now one minute and eighteen seconds to retrofire,” announced Paul Haney, the voice of NASA, to the millions of Americans following the maneuver on live television. Eighteen seconds later, he added, “One minute on my mark. Mark!” Then, “Thirty seconds, mark!”

And finally, “Ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, one, retrofire!”

In the spacecraft, Lovell and Aldrin felt four hard bumps and heard four loud bangs as the engines lit, slamming them with more than ten thousand pounds of thrust squarely in their backs.

“Retrofire!” Lovell, the commander, echoed.

“Holding it steady,” Aldrin answered.

The engines fired for just five seconds, but the physics and the arithmetic governing the maneuver meant that that was enough to send the astronauts on a controlled high dive through the steadily thickening air, which would cause temperatures of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit to bloom across the heat shield at the bottom of their capsule. Less than half an hour later, they splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean, seven hundred miles southeast of Cape Kennedy in Florida, within sight of the prime rescue vessel, the USS Wasp.

“Son of a gun!” Aldrin exclaimed as the spacecraft slammed into the choppy Atlantic waters.

“Boy! Boy! Boy!” Lovell responded.

“Gemini 12, Houston,” called astronaut Pete Conrad, the capsule communicator in mission control, as TV cameras picked up the sight of the spacecraft. “Smile! You’re on the tube!”

For the historical record, Lovell did smile and Aldrin did smile and America smiled too. Because with the successful splashdown of Gemini 12, the twenty-month Gemini program, which had seen the US launching men into space at the rate of one mission every eight weeks, during a stretch in which the much-feared Soviet Union had not succeeded in sending any cosmonauts aloft at all, had come to its triumphant end. In that twenty months, NASA and America had learned how to walk in space, to fly long-duration missions in space, to navigate in space, to rendezvous and dock with another vehicle in space—in short, to do every little thing it would be necessary to do if the US were going to meet the pledge the martyred president John Kennedy had made more than five years before: to have American boots on the moon before the end of the decade.

The gripping and glittery tale of the Gemini program—one defined by its successes, yes, but also by its tragedies and losses and deaths and near deaths—has never been fully told before. Americans know well the story of the Mercury program, when such Mount Rushmore names as John Glenn and Al Shepard and Gus Grissom and Wally Schirra made the nation’s first journeys in space. And the nation surely knows of the Apollo program, when human beings first ventured moonward.

But we know less about the story of the Gemini program—which gave us the likes of Lovell and Aldrin and Conrad and Neil Armstrong. That is not as it should be.

Over the arc of the last three generations, the adeptness of Gemini, the capabilities of Gemini, the mechanical genius of Gemini, not to mention the sublime skills of the men who piloted the Geminis, have had an outsize and often unappreciated impact on geopolitics, technology, and the fundamental science of space travel itself. It was the Gemini, certainly, that gave the US the cosmic edge over the Soviet Union in the original space race, contributing to a cascading series of economic, engineering, and political victories that helped bring the original Cold War to a peaceful end, with the West ascendant and the former Soviet Union consigned to history.

It was the Gemini program that provided the glimmers of good—indeed, often dazzling—news during some of the darkest periods in America, in the midst of the bloody and riven 1960s, bringing not just the public but politicians together in the shared goal of making America the dominant power off the planet.

It was the Gemini program, too, that helped give rise to the global cooperation in space that exists today with NASA, the European Space Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, and more than fifteen nations collaborating not just aboard the International Space Station but in the new Artemis program, which aims to have boots back on the moon by the end of the 2020s. Every docking a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft makes with the space station, every space walk any astronaut from any nation takes, every step an Apollo astronaut took on the lunar surface, every one of the 135 space shuttle missions, every scientific experiment conducted aboard any active spacecraft flows directly and indirectly from lessons learned more than half a century ago when the very first Geminis with their very first astronauts made their very first flights into the void.

America and the world have overlooked Gemini too long, have forgotten its achievements too easily, have wrongly assigned it to the spot of forgotten middle sibling in the Mercury-Gemini-Apollo troika. But Gemini was one of the most thrilling and harrowing and uplifting exercises ever attempted in the history of space travel. I and others have told the story of the Mercury program. I and others have told the story of the Apollo program. With this book, I aim to tell an equally powerful story of the Gemini program and, in doing so, help complete the historical record.

PROLOGUE

Space Walk at the Brink: June 5, 1966

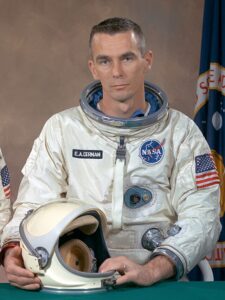

The last thing Tom Stafford wanted to do was cut Gene Cernan loose in space. Stafford liked Cernan; he had trained hard with Cernan. For more than a year, the two of them had worked together to get ready for their three-day flight of Gemini 9, and now, in early June 1966, they were actually aloft. But the business of cutting Cernan loose was all at once a very real possibility.

Stafford, the commander of the mission, was inside the spacecraft, buckled into his left-hand seat. Cernan, the junior pilot, was outside, dangling—actually spinning, tumbling, and flailing—at the end of a long umbilical cord, completely unable to control his movements, much less make his way back to the small open hatch on his side of the spacecraft and maneuver himself inside.

It was Deke Slayton, the head of the astronaut office, who first raised the possibility of what Stafford should do in a situation like this—and for Gemini 9, the warning seemed especially important, since the flight had been snakebit from the start. Just four months earlier, two good men—rookie astronauts both—had died a fiery death trying to get the mission off the ground. The next month, two other good men—Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott—had nearly lost their lives when their Gemini 8 spacecraft spun out of control 186 miles above the earth’s surface. Now it was Gemini 9’s turn, and NASA’s run of bad luck seemed to be continuing.

Twice, at the end of May, Stafford and Cernan had suited up and climbed into their spacecraft in preparation for liftoff, and both times, technical problems had caused the launch attempt to be scrubbed. It was before the second of those attempts, when Stafford and Cernan were still in their long johns, preparing to climb into their pressure suits, that Slayton appeared in the suit-up room. Completely ignoring Cernan—not even making eye contact with the rookie astronaut—he addressed Stafford.

“Tom,” he said, “I need to have a few words with you in private.”

Cernan looked at Stafford with a questioning expression, and Stafford merely shrugged in response. That hardly appeased Cernan. Yes, he was a first-timer in space, while Stafford had flown just six months before on the successful flight of Gemini 6. But the two men were now one crew, and anything that was said to the commander ought to be said to the pilot as well. That wasn’t what Slayton wanted, however. He escorted Stafford out of the room and in quiet tones laid down what was NASA’s life-and-death law.

Only once before, on the flight of Gemini 4 just a year earlier, had an American astronaut walked in space, and that had been merely a twenty-minute float outside the cabin door, with pilot Ed White slightly maneuvering himself this way and that with a handheld zip gun before hurrying back inside and sealing the hatch. Cernan’s space walk would be much more ambitious, lasting hours, with the astronaut climbing all over the spacecraft to deposit and collect experiment packages before making his way to the rear end of the ship where an astronaut maneuvering unit—an air force–built jet pack known as the AMU for short—was stowed. Cernan would be expected to climb into the backpack and fly free in space, connected to the ship only by a long, thin, nylon tether.

The entire exercise posed enormous risks, and Slayton was well aware of the mortal math involved in that.

Up to now, NASA had launched twelve crews of men into space—six aboard the one-man Mercury spacecraft, and six more so far on the first six Gemini flights, from Gemini 3 to Gemini 8—and all twelve of those crews had come home safely. NASA wanted to keep those numbers as close to perfect as possible. Sending two men into space aboard Gemini 9 and bringing two men home was the objective, of course. But if something happened to Cernan when he was free-floating outside—if he became incapacitated, unconscious, or was otherwise beyond rescue—Slayton would not stand for Stafford playing the hero, remaining in space with the cabin door open and dying along with his crewmate. In such a situation, Stafford was to disconnect the umbilical cord that linked his junior astronaut to the spacecraft, seal the hatch, and come home alone, leaving Cernan, a thirty-two-year-old naval aviator, to become nothing more than a lifeless satellite of the earth.

Cut him loose, Slayton said to Stafford. If it comes to that, cut him loose.

Stafford nodded his understanding, left Slayton, and returned to the suit-up room.

“What was that all about?” Cernan asked.

“Everything’s fine, Geno,” Stafford answered. “No big deal.”

But now, one week later, with the third attempt of the Gemini 9 launch having at last succeeded and the crew in orbit 194 miles above the earth, it was a very big deal indeed—with Cernan in very big trouble.

Certainly, Gene Cernan was accustomed to taking chances—especially when he was a younger man, living the hot-rod aviator life that every rookie naval pilot lived. Nine years earlier, in 1957, he was practicing bombing runs at Naval Air Station Miramar in San Diego, California. The drill called for him to buckle into the cockpit of his FJ-4B Fury with a dummy warhead strapped to the bottom of the jet.

His target was a 40-foot space on the ground, barely wider than the Fury’s 39.1-foot wingspan, marked on either side by 10-foot wooden poles driven into the earth. The goal: Approach the target at 300 knots—or 354 miles per hour—drop the simulated bomb near the ground, and then haul ass up and away at 500 knots—or 575 miles per hour—escaping the imaginary blast the dummy explosive would have unleashed if it had been real.

Cernan had flown the maneuver countless times, always successfully, but on one especially exuberant day, he decided to take his chances—flying faster and lower and more hotdoggedly than he ever had before.

His reasoning was simple: In a real shooting war, the faster and lower he flew, the less chance the Soviet enemy would have of spotting him on radar. So Cernan took off, and Cernan flew low and Cernan flew fast—so low and so fast that when he approached that 40-foot space, his 39.1-foot-wide airplane clipped one of the wooden poles, shaking and jolting the plane and emitting a loud cracking sound. The plane still flew, and Cernan managed to land it safely, but the moment he did, the ground crew rushed out to meet him. One of the plane’s gun turrets was filled with a solid cylinder of wood that had been jammed into it from the post. Worse, the plane had been torn open along its starboard side, with a long gash running from the nose all the way down to the wing. A little more ripping, a little more tearing, a little more violence from the hot dog flying, and Cernan would not have made it home at all that day. Later, he and his squadron mates joked about it over beers, but it was a shaken Cernan who drank and laughed that night. It was the last time the young flier would ever depart from flight rules and strict training protocols.

In preparing for his space walk, Cernan maintained that playit-straight attitude, spending scores of hours training in NASA’s weightlessness-simulating jet—a KC-135 cargo plane nicknamed the “vomit comet” because it would take trainee astronauts on flights that amounted to a long series of roller-coaster-like parabolic loops, with twenty seconds or so of zero-g occurring at the top of each parabola.

The drill involved practicing a spacewalking task in the twenty seconds of weightlessness you got, waiting out the next minute of full gravity as the plane dove to the bottom of its trajectory and climbed back up, then continuing your zero-g rehearsals in the next twenty seconds of over-the-top free float. It was a slow and painstaking way to learn to maneuver in weightlessness—and plenty of men did not make it through the day without the vomit part of the vomit comet name having its way with them. Cernan, once an aviator who liked taking risks, would be nowhere near as cavalier in practicing for what was only America’s second space walk—and its first truly ambitious one.

On Sunday, June 5, 1966, at 5:30 a.m. Houston time, two days after launch, Cernan began his space walk, or what NASA preferred to call, in the agency’s arid argot, his extravehicular activity—or EVA. The precise timing of the EVA was in some respects arbitrary, since there actually was no morning or night in spaceflight; the astronauts circled the planet every ninety minutes, experiencing sixteen sunrises and sixteen sunsets per day. So to keep things tidy, they set their watches by the time it was in Houston, where mission control was located. If it was 5:30 a.m. in southeast Texas, it was 5:30 a.m. aboard Gemini 9.

Cernan would need a long time to prepare for his EVA. The ground crew equipped him with an eleven-page checklist that covered everything from donning a chest pack, which would provide him with oxygen, power, and communications; to unstowing the twenty-five-foot umbilical cord that would keep him safely attached to the Gemini spacecraft; to pressurizing the modified EVA space suits both he and Stafford were wearing. Gemini astronauts who were flying missions in which no EVA was taking place could afford to wear lighter suits, since the cabin itself was pressurized, surrounding them with artificial atmosphere. But once the hatch was opened and Cernan exited, both men would be exposed to the hard vacuum of space, and that required more robust suits—seven layers thick.

Even before pressurizing his suit, Cernan found the umbilical cord almost impossible to manage in the weightless environment of the spacecraft. The infernal thing floated and twisted and tangled itself, resisting all of Cernan’s efforts to keep it rolled and controlled.

“Canary,” Stafford radioed down to the Canary Island tracking station, “you can inform Houston we’ve got the big snake out of the black box.”

Once Cernan and Stafford inflated their suits, things became even more difficult, involving both the challenge of maneuvering the snake and the simple matter of moving at all. As the suits were inflated to a pressure of 3.5 pounds per square inch, they hardened and stiffened, making maneuvering in them almost impossible. It took all of an astronaut’s strength merely to bend an elbow or flex a knee. For Stafford, this would present little problem, as he would remain seated inside the spacecraft throughout the EVA. For Cernan, who was supposed to maneuver balletically around the Gemini 9 spacecraft, it would be a different matter entirely.

Stafford depressurized the cockpit, matching the vacuum inside to the vacuum outside so that the hatch would not blow open and fly free from interior air pressure when it was unlatched. Then Cernan reached up to the hatch’s handle and tried to open it, but it wouldn’t budge.

“Man, the hatch is stiff,” he informed both Stafford and the ground.

Using both hands, and already struggling against the bulk and unmaneuverability of the suit, he managed to push the handle inch by inch—millimeter by millimeter, it seemed—until at last the hatch opened and the trace amount of air that remained inside the spacecraft breathed itself out and away. Before Cernan even exited the ship, he and Stafford had to deal with the routine business of throwing out a bag of trash—mostly empty food wrappers—that they’d accumulated during the two days they’d spent in space so far. Stafford passed the bag to Cernan, who heaved it weightlessly outside the open hatch.

“Okay, we’ve gotten rid of the garbage,” Stafford told the ground.

Now Cernan tentatively raised himself up, placed his feet on his seat, and stood in the open hatch. He gaped at what he saw. The twin windows in the Gemini spacecraft measured only six inches by eight inches, affording the astronauts enough of a view to conduct some narrow photo reconnaissance of Earth and maneuver their spacecraft throughout their orbits. But that peephole field of vision was nothing compared to what Cernan now had. Gemini 9 was flying over Baja California, and Cernan could see the blue of the water against the green-brown spit of land and the rusty red surface of the desert southwest stretching in all directions.

“Hallelujah!” Cernan exclaimed. “Boy, is it beautiful out here, Tom.”

“It sure looks pretty,” Stafford said, taking in the minimal view his little window afforded him.

“I’ll grab my Hasselblad and take a picture of that,” Cernan said, photographing the scene with the camera attached to the front of his suit.

Cernan’s first jobs, before he even emerged fully from the spacecraft, were to attach a movie camera on an external mount to film the EVA and install a mirror to the exterior of the ship so that Stafford could see him as he maneuvered around the spacecraft and retrieved a micrometeorite experiment that had been attached to the Gemini to measure the impact of microscopic space dust.

That job done, Cernan emerged fully from the spacecraft and prepared to make his way along its flank to its aft end, where the AMU was stowed and waiting for him. The journey along the Gemini, which measured only eighteen feet and five inches from bow to stern, proved to be well-nigh impossible. NASA and Cernan may have had their own ideas about how to maneuver at the end of a twenty-five-foot umbilical cord—and Cernan’s training in the vomit comet might have left him thinking he knew what he was doing—but Isaac Newton had his ideas too, and those prevailed. Every physical action Cernan took produced an equal and opposite reaction in the snake; if Cernan moved out, the snake pulled him in; if Cernan moved left, the snake flung him right.

The out-of-control motion radiated down to the spacecraft itself, which began yawing and pitching in response to the force. Such unwanted motion would have normally called for Stafford to fire his thrusters and stabilize the ship, but he dared not do that with Cernan outside, where the thruster exhaust could burn through his suit.

Instead, it was up to Cernan to stabilize himself. He grabbed for Velcro patches NASA had attached to the exterior of the spacecraft to help him gain his purchase, but the whipsawing of the umbilical cord proved more powerful than the hold the Velcro could provide. He also reached for handholds that had been installed on the exterior of the ship, but they had been placed multiple feet apart—the thinking being that Cernan would have an easy glide alongside the spacecraft and the handholds would be necessary only in an emergency. Instead, he continued flopping around at the end of the umbilical cord, utterly helpless to control his own motions. “You’re kind of rocking the boat,” Stafford radioed to Cernan from within the jerking Gemini. He then glanced at the mirror Cernan had installed and was alarmed at what he saw. “Looks like you’re upside down and have all sorts of snake around you,” Stafford said.

“I can’t get where I want to go,” Cernan answered. “The snake is all over me. It’s pretty much a bear to get at these things because the handrails are so far back.”

Finally, through a combination of extreme exertion, Newtonian dynamics, and no small amount of sheer dumb luck, Cernan managed to swing in the direction of the spacecraft, slam into its flank, and grab hold of one of the handrails. Now, at last, he got some additional help.

Toward the back end of the craft, NASA had attached a long cable running the rest of the way to the end of the craft that Cernan could grab on to, hand over hand. That, too, was exhausting work, as he could move only a few inches at a time before stopping and gathering in the snake to prevent it from yanking him away from his tenuous hold on the cable.

Cernan had been outside for more than an hour now, enough to move from the daytime side of Earth, where the temperature on him and the spacecraft was a blistering 270 degrees Fahrenheit, to the nighttime side, where it was a frigid -270 degrees Fahrenheit, and back to the sunlit side. His space suit was designed to keep the heat and cold within a survivable range, but all it took was a few degrees above or below that limit to cause him to feel a sweltering heat or a chilling cold. Sweat now began to pour down his face and sting his eyes—though he was helpless to wipe them since he was sealed inside his suit and helmet. Worse, his visor began to fog up from the dampness of the sweat, obscuring his vision.

On the ground, at a console in Houston, flight surgeon Charles Berry read Cernan’s heart rate at 155 beats per minute, or about what it would be if he were running up 120 stairs each minute.

“How are you doing now, Gene?” Stafford asked.

“Okay,” Cernan answered. “I’m going to slow down and take a rest.”

Cernan allowed himself to catch his breath and, he hoped, slow his heart, and then inch by inch, his visor running with condensed moisture, made his way semi-blindly to the back end of the spacecraft, where the AMU, which the air force engineers still expected him to don and fly, waited for him. But when he reached the aft of the ship, he encountered a nasty—and potentially deadly—surprise. That end of the spacecraft had been the part that was attached to the Titan II rocket that had blasted the crew into space; when the rocket separated just before the Gemini capsule reached orbit, it left a sawtooth, razor-sharp spear of metal behind, an obstacle Cernan would have to climb around without slicing open his suit and suffering an instant and fatal depressurization.

He reported the problem to Stafford and then, ever so carefully, negotiated that knife edge. When he had gotten past it, he tumbled gratefully into a recessed area at the back of the ship, where, with all his exertion, he fought his rigid suit and bent it into a position that would allow him to sit. He looked to his right, where the AMU was stowed— and he sighed at what lay ahead.

Flying the AMU meant more than just donning the backpack, firing it up, and taking off. Attached to the unit was a thirty-five-item checklist, each step of which had to be completed, in sequence, for the thing to fly. The first chore was to switch on the lights attached to the unit so that he could read the checklist. He threw the proper switch and only one of the little lamps worked. Squinting through the dim illumination and his sweat-covered visor, he did his best to follow the checklist, but the work of strapping into the contraption and configuring its controls was exhausting, and Cernan began to pant. On Berry’s screen in Houston, the astronaut’s heart rate now read 180 beats per minute.

Next, according to plan, Cernan disconnected from the umbilical cord that attached him to the ship and clipped on instead to one that was connected to the AMU. Immediately, to the flight surgeon’s alarm, the signal from the astronaut to the ground flickered out. Cernan’s heart could accelerate to the level of cardiac arrest and the Houston doctor would never know it. And his heart was accelerating indeed as the unfiltered sun poured over him and the recessed metal skillet that was the rear of the spacecraft.

“We’re really cooking back here,” Cernan gasped.

From Stafford’s window, he could see that Gemini 9 was approaching another sunset. “Okay, Gene,” he said. “Nighttime coming your way shortly.”

But nighttime, Cernan suspected, would only present another problem, and he was right. No sooner did the spacecraft move into the shadowed part of the earth and the temperature drop to -270 degrees than the sweat that covered his visor froze over, blinding him completely.

Cernan leaned forward, rubbed his nose against the inside of the visor, and opened a tiny hole in the ice. He could see the lights of Australia beneath him.

“How are you doing, Geno?” Stafford asked.

“Really fogged up here,” Cernan said, continuing to work as well as he could through the AMU checklist. The same poor connection to the AMU that was preventing data from Cernan’s biomedical sensors from reaching the ground also now disrupted the communications between the two astronauts.

“Can you see anything, Geno?” Stafford asked. “Can you understand me? Geno? Geno? Yes or no?”

Cernan responded, but whatever he was saying was unintelligible.

Stafford contemplated his and his pilot’s options. Another daytime was soon approaching, which would cook Cernan again, followed by another nighttime, which would freeze his visor solid once more. Cernan could not maneuver with the main umbilical cord, much less, Stafford guessed, with the untested AMU, and every additional minute he remained outside was another minute of mortal danger.

That, for Stafford, was it. He knew Cernan and, after training with him for more than a year, understood the man’s mettle. Cernan would keep working back there, with his vision gone, his heartbeat triphammering, a razor-like piece of metal threatening to tear his suit open wide, the light and shadow of the day and night tormenting him, all the while trying to fly the air force’s cursed AMU if it killed him—which it might.

As commander of the ship, Stafford had the authority to make any decision that concerned the conduct of his mission and the welfare of his crew, even if the flight controllers on the ground didn’t agree. The EVA, he decided, was over.

“Okay,” he said, partly to Cernan and partly to the ground. “No-go. The link is terrible. Did you understand? Geno? Do you hear me? I said no-go. We’re aborting.”

Cernan did hear him. He released a long breath—both with relief and with trepidation. Aborting the EVA was easy enough. Making his way blindly back around the jagged metal shard, moving along the side of the Gemini—finding the handholds and Velcro and the ship’s aft cable without the benefit of vision, all the while battling to keep his heart rate under control—was no small matter. Then, too, there was the matter of folding himself back inside the tiny seat of his little spacecraft and getting the hatch closed while wearing a space suit that kept him as rigid as a mannequin. Gene Cernan had left Gemini 9 to walk in space.

If his suit tore or he became incapacitated or he could not reenter the ship at all, there was no guarantee that walk would ever end.

“I don’t think I’ll make it that way,” Cernan said, flicking his unseeing eyes back around the rear end of the ship toward the front. But that way, as both astronauts knew, was the only way. The comment was all Cernan said that sounded like surrender—but it was enough.

Stafford heard the transmission clearly and nodded silently and somberly. Inside his head, Slayton’s words echoed hauntingly. Cut him loose.

Start listening to an audio excerpt of Gemini!

Gemini copyright © 2025 by Jeffrey Kluger. All rights reserved.

Jeffrey Kluger is Editor at Large at Time, where he has written more than 45 cover stories. Coauthor of Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13, which was the basis for the movie Apollo 13, he is also the author of 13 other books including his latest book Gemini: Stepping Stone to the Moon, the Untold Story.

The post Featured Excerpt: Gemini appeared first on The History Reader.