Written by Nicky Hughes

Berthold Lubetkin, who co-founded the radical 1930s architectural practice, Tecton, was a leading figure in the development of Modernist architecture in Britain.

His architectural education coincided with the Russian Revolution in 1917 and he became immersed in the Constructivist movement, in which all the arts were brought together in the service of social progress.

Lubetkin’s influential designs include London Zoo’s Penguin Pool, works at Whipsnade and Dudley Zoos, as well as London’s Finsbury Health Centre, the Highpoint apartments, and social housing such as the Spa Green and Bevin Estates.

Lubetkin’s early influences

Lubetkin was born in 1901 into a middle-class family in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, then part of the Tsarist Russian empire.

As a teenage student of technical drawing, attending a private school in Moscow, he witnessed and participated in the life-changing tumult of the 1917 Russian Revolution, which overthrew the Tsarist monarchy. This experience informed his sense that a radical renewal of society was possible.

He moved first to Berlin in 1922, then to Warsaw, Poland, before settling in the artistic heart of Europe, Paris, for 6 years. His architectural studies during that period included modern building construction, as well as being tutored by Auguste Perret (1874 to 1954), a French pioneer in the architectural use of reinforced concrete.

Lubetkin also encountered leading figures of the European avant-garde, including the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier (1887 to 1965), a pioneer of the modern movement in architecture.

In 1928, he partnered with the young architect Jean Ginsberg (1905 to 1983) who he had met in Warsaw. He designed his first project for Ginsberg’s father, 25 Avenue de Versailles, which survives as Lubetkin’s only extant work from his Paris years.

Intending to return home to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) at some point to participate in the Soviet reconstruction programme, Lubetkin first participated in architectural competitions, as well as making a trade trip to London, where he was warmly received by leading figures in the British architectural establishment.

In 1931, Lubetkin decided to emigrate to London, perceiving Britain as an enlightened country ready for his Modernist, socially driven architectural ideas. He settled in Hampstead.

The founding of Tecton

In the 1930s, Hampstead in London was a focal point for many avant-garde artists and architects, including those fleeing from Nazi Germany.

The architects who found refuge in Britain pioneered a step change in terms of architectural design. They brought radical Modernist ideas and technical innovation, demonstrating the exciting freedoms and design possibilities of new building materials.

Lubetkin strongly believed in collaborative working and established the architectural practice, Tecton, when he arrived in the country. The 7 members included recent graduates from the Architectural Association School of Architecture, one of these was Margaret Church, who Lubetkin married in 1939.

The early architectural works of Tecton

In the early days of Tecton, there was not enough work to sustain the practice, so members took on various individual commissions instead.

One of Lubetkin’s initial commissions came from a speculative developer and was his first domestic project in Britain: a row of houses sandwiched within a suburban Victorian terrace. They were designed in an uncompromisingly modern idiom and constructed of reinforced concrete.

The Tecton group designed several relatively minor works in the 1930s, including private houses, but the practice was desperate for big projects.

Their break came from an unlikely quarter: London Zoo, which had recently acquired 2 young gorillas from the Congo, Mok and Moina.

Tecton’s zoological designs

Gorilla House, London Zoo

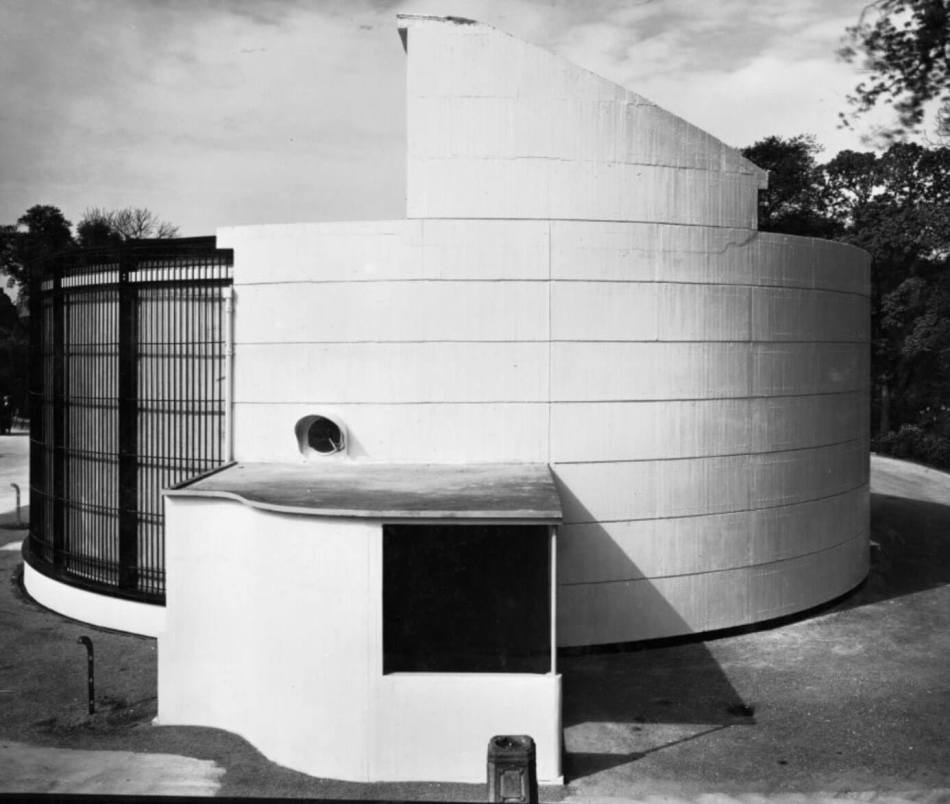

The purpose-built Gorilla House was Tecton’s first significant commission, secured via fortuitous connections, which included the zoo’s 2 principals, both being committed socialists.

Ove Arup (1895 to 1988), a pioneering structural engineer and specialist in reinforced concrete construction, worked with Tecton on all of their key work including the Gorilla House. Arup believed in a creative collaboration between architects and engineers based upon shared aims.

The architecture was informed by Lubetkin’s research into the habits and needs of gorillas. This was typical of the highly disciplined way he worked. His and Tecton’s designs were always supported by detailed scientific and technical inquiry.

The project was widely praised and, even before its completion, London Zoo commissioned Tecton to design a new enclosure for its penguins.

Penguin Pool, London Zoo

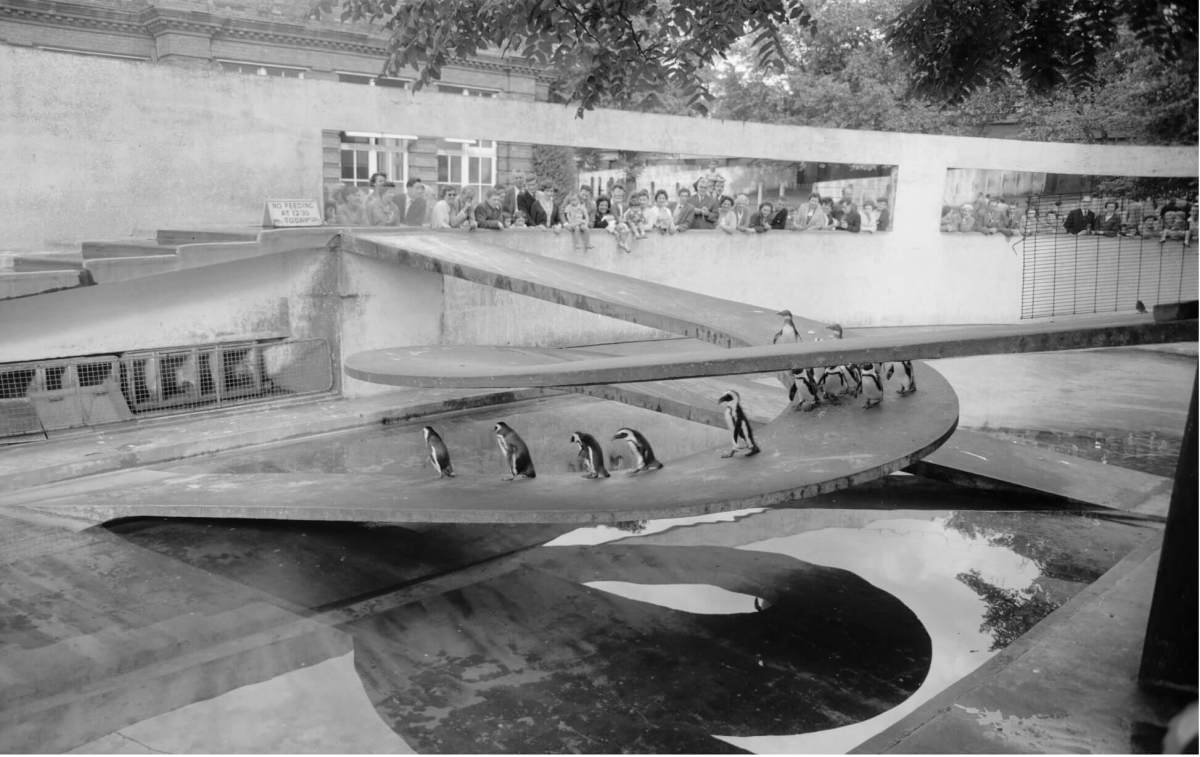

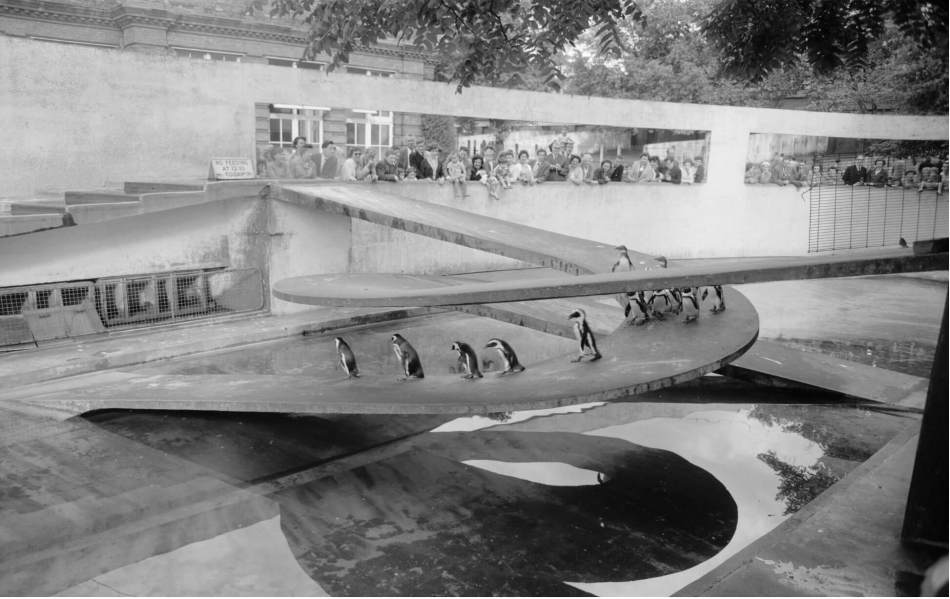

Lubetkin’s elegant Penguin Pool was built around an elliptical pool, with 2 spiralling and intertwining ramps.

It was a tour de force of reinforced concrete construction, meeting with instant acclaim by both the public and the architectural world, establishing Lubetkin and Tecton’s reputation internationally. It remains Lubetkin’s most famous zoological design.

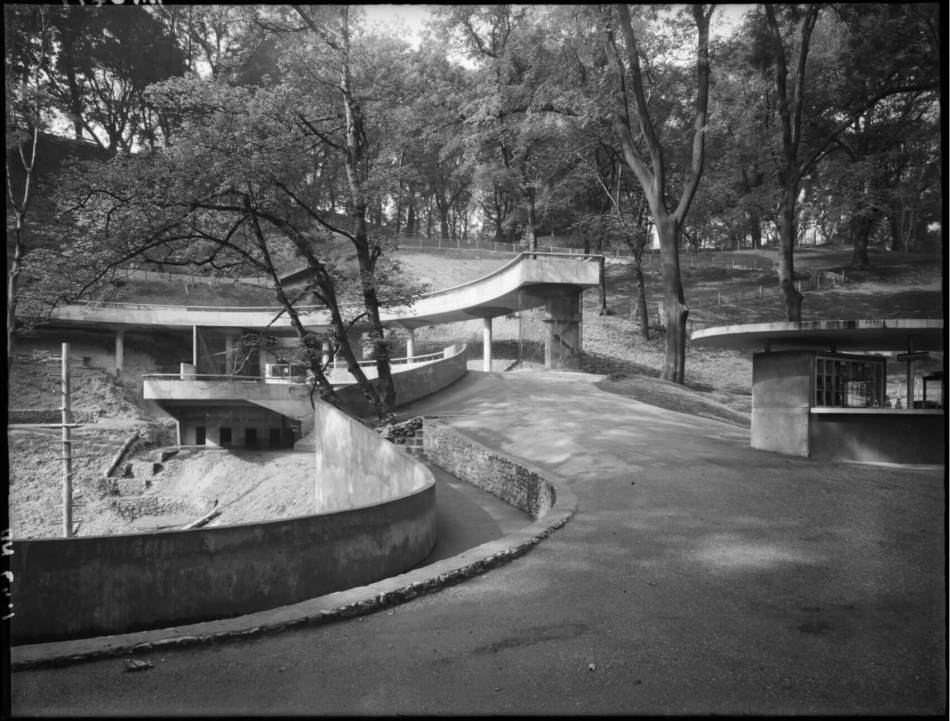

Animal Enclosures, Dudley Zoo

Tecton designed many other zoological structures in the 1930s, both for London Zoo’s associate zoo in Whipsnade, Bedfordshire, including the Elephant House, as well as the Bear Ravine and Polar Bear Pit at Dudley Zoo, West Midlands.

The 12 Tecton structures at Dudley Zoo represent the greatest surviving collection of their zoological works. All are listed Grade II or Grade II*.

Private flats: Highpoint I and II

Lubetkin had met, through personal contacts, Sigmund Gestetner (1897 to 1956), chairman of the office equipment company of the same name. Gestetner may have initially intended to build accommodation for his employees: he gave Lubetkin a virtually open brief for the design and to find suitable local land.

Lubetkin’s Highpoint I re-examined every aspect of modern communal living from first principles, from the double-cruciform plan, which maximised daylight and ventilation, to the layout of the flats. It was a building of technical sophistication and cool restraint, rendered in off white.

It was the most advanced block of flats of its time: constructed of reinforced concrete, with extensive glazing via long steel folding windows, glass bricks, elegant white pillars and landscaped gardens, as well as central heating, stainless steel sinks, built-in refrigerators, chrome door handles and laundry chutes.

Many eminent designers of the day approvingly visited Highpoint I soon after its completion, including Le Corbusier.

Highpoint I and its successor, Highpoint II, are amongst the most celebrated of all Lubetkin’s works. Highpoint II, built between 1936 and 1938, was smaller and more luxurious with Greek-style caryatids supporting the entrance canopy, marble and tiling throughout. Unexpected or surreal touches continued in the penthouse flat that Lubetkin designed for himself, which incorporated rustic planks, cow-hide furniture and a curved roof vault painted sky.

Architecture and health

Finsbury Health Centre, London

In 1936, Lubetkin and Tecton were commissioned by the Labour-controlled Finsbury Borough Council to realise the council’s radical vision of a new state-of-the-art health centre.

The project was pioneered by the visionary Dr Chuni Katial, chair of the public health committee and, from 1938, the country’s first Asian mayor, along with council leader, socialist Harold Riley.

The building, constructed of reinforced concrete with faience tiling and deeply recessed curved glass walls, was designed in an H-shaped plan. The entrance is flanked by two splayed wings which stretch out to embrace visiting patients.

It was a symbiosis of progressive political ideals and Lubetkin’s belief that architecture could affect social change.

Finsbury at that time was an overcrowded borough, with slum housing, deprivation and poor public health.

The centre would centralise healthcare services that had generally been provided piecemeal across the borough, with facilities that included a tuberculosis clinic, dispensary, dental surgery, foot clinic and solarium.

The centre’s interior design was symbolic of the optimism of a better, healthier future: bright modern colours, clean surfaces, the glass brick walls filling the spacious entrance with light.

There were contemporary chairs designed by Finnish architect and designer, Alvar Aalto, and murals by Gordon Cullen. It was intended to have the feel of a relaxed drop-in centre, in stark contrast to the cramped conditions of most existing surgeries at the time.

The Second World War paused Tecton’s plans to design new social housing to replace Finsbury’s slums.

However, the wartime coalition government itself was moving towards the idea of building a more just and equal society post-war.

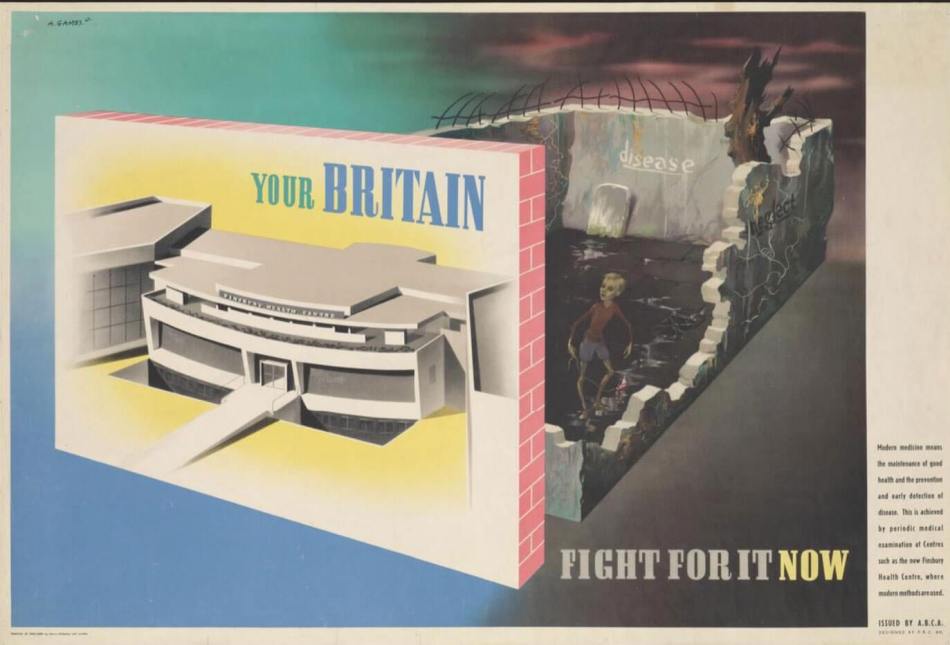

Games’ wartime poster, above, of the Finsbury Health Centre, with its rallying call ‘Fight for it now’, was one of several government propaganda posters depicting this bright new future. Modernist architecture was both its embodiment and its image.

The stage was set for the new incoming post-war Labour government to deliver a radical era of social change. Lubetkin, Tecton and Ove Arup’s work would become a key element.

Lubetkin and Post-War social housing

Spa Green Estate, Clerkenwell, London

The Spa Green Estate was the first and finest social housing scheme created by Tecton. It was commissioned by Finsbury Borough Council on a slum clearance site. After the post-war creation of the welfare estate, Lubetkin’s architecture – and the social and political ideals that underpinned it – moved from the radical fringes to the mainstream.

At last, Lubetkin was able to fully put into practice his strong socialist principles of how modern design of could improve the living conditions of ordinary working people.

The Spa Green Estate offered flats with facilities that, until then, had been the preserve of the better off: lifts, plentiful daylight, balconies, central heating, fitted kitchens, a waste disposal system, gas and electric appliances, as well as a roof terrace for drying washing and socialising.

Bevin Court, Islington, London

After the Tecton practice formally dissolved in 1948, Lubetkin created a new partnership with original Tecton member, Francis Skinner, and Douglas Bailey. Bailey had been Lubetkin’s deputy during the latter’s brief and unhappy tenure as architect-planner of the new town of Peterlee in County Durham.

Lubetkin’s role as master planner was undermined by the fact that the designated area overlaid an active coalfield, requiring protracted negotiations with the landowner, the National Coal Board. He submitted an ambitious master plan in January 1950 but it was too late; his working relationship with the development corporation had deteriorated to the point that he departed from the project just a few months later.

Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin worked on a number of social housing estates for Finsbury Borough Council throughout the 1950s, including Bevin Court.

The striking staircase within Bevin Court is perhaps Lubetkin’s most idiosyncratic single post-war achievement: a sculptural piece of concrete geometry, now restored to his original colour scheme, that pays homage to his Constructivist origins.

Other social housing projects

Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin also designed a number of other important social housing projects, including 3 for Bethnal Green Borough Council: the Lakeview Estate (1953 to 1956), the Dorset Estate 1 (951 to 1957), built on slum clearance land and completed in 1966 with the 19 storey block, Sivill House, and Lubetkin’s colossal final urban vision, the Cranbrook Estate, 1955 to 1966.

Later life and legacy

From the 1950s Lubetkin grew disillusioned with post-war politics and the architectual profession, and increasingly withdrew from active practice

After relocating to rural Gloucestershire in 1939, Berthold and Margaret Lubetkin moved to Clifton in Bristol in 1969, where they spent the remainder of their lives. Lubetkin gradually re-emerged into public life. He was awarded the RIBA Gold Medal for Architecture in 1982 and John Allan’s perceptive biography was published a decade later.

His work had an extraordinary legacy. Tecton members and associates went on to forge high-profile careers of their own, among them Denys Lasdun (1914 to 2001), founding member of Tecton in 1932 and architect of London’s National Theatre.

Lubetkin died in Bristol on 23 October 1990.