by Christian Alvarado

The Mau Mau conspiracy will fail. There is no doubt about that. It started too soon and was on too small a scale. The forces on the side of law and order are being constantly strengthened in numbers and by training. But it is not enough to crush the Mau Mau: How are we to deal with the evil ideas which, largely through fear, are dominating a tribe of more than a million Africans?

—Stephen Foot, “The Ideological Struggle in Africa”

Published in The Star (Johannesburg) on October 21, 1953, the above passage is emblematic of a genre of writing about the Mau Mau Uprising in late-colonial Kenya (1952–1960), which positions the movement as the result of “evil ideas” spread through the work of a conspiracy. From the first rumors of attacks on settler plantations in Central Province, the composite factions of freedom fighters generally glossed as “Mau Mau” became known throughout the world as an icon of violent, African revolution. Stephen Foot, a British businessman, writer, and author of the article in The Star, rehearsed a formulaic set of elements that have conditioned pro-Western rhetoric about the Uprising since its outbreak in the fall of 1952—framings anchored in a much broader, and older, colonial tropology but further influenced by the particularities of his own politics. Most pertinently, prior to penning articles on his travels in Africa, Foot became a member and staunch advocate of the anti-communist Moral Re-Armament (MRA) movement. Founded in 1938, the MRA had its roots in American evangelical and revivalist traditions and sought to remake a fallen world through individual transformation and spiritual renewal.

The establishment of relationships with many figures who would come to serve in high-ranking capacities across the African continent during and after the decolonization era—including Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, Nigeria’s Nnamdi Azikiwe, and Kenya’s Tom Mboya—became central to the MRA’s aspirations during the Cold War. The connections forged with such figures, however, obscure the extent to which the MRA was rooted in reactionary politics, most notoriously distilled in founder Frank Buchman’s assertion of pro-Nazi positions and statements. “Human problems aren’t economic,” Buchman proclaimed, “They’re moral, and they can’t be solved by immoral measures. They could be solved within a God-controlled democracy, or perhaps I should say a theocracy, and they could be solved through a God-controlled Fascist dictatorship.”

It was this vision of a global order populated by patchworks of theocracies and “God-controlled Fascist dictatorships” that the MRA worked to establish as a bastion against the diffusion of international communism, anti-colonial race-consciousness, and atheism. Whatever its theological pretensions, the MRA was part of a mycelial network of reactionary crusaders that have traversed continents and spanned oceans since the Russian Revolution and the First World War. These entangled events speak to two of the most consistent elements of conspiracy theories regarding political violence over the last century: anti-communism and the malevolent machinations of inordinately powerful “outsiders within.” And it is as a part of this interpretive community of reactionary conspiracists that Foot’s comments on the “Mau Mau conspiracy” must be read. Doing so centers our attention on how this conspiracy was read outward from its origin in Central Kenya and why it was framed as a battlefront in the emergent “ideological age” of the global Cold War.

Undoubtedly, digital culture has radically changed how people across the world interface with conspiracies and other speculative narratives like them. Today’s “post-truth” discursive landscape, however, looks far less unprecedented than it might first appear when situated as a continuation of distinct colonial and post-colonial discursive tendencies shaped over centuries of imperial paranoia and politicking. In what follows, I want to suggest that one can best understand conspiracism in the present as a re-casting of a genre of thought that has been part and parcel of Western discourses about change, the Other, and civilizational decline for as long as the self-conscious idea of “the West” has existed itself. Decades before internet conspiracists posted their way into the mainstream of Western European and American societies, the same rhetoric and violence enabled by conspiracies remade the political economy of the world by shaping the processes of colonization and decolonization in Africa, Asia, and Latin America—including through the circulation of what I call here the “Mau Mau conspiracy.”

Constructing Conspiracy, Narrating Mau Mau

In its narrative proliferation, “the Mau Mau conspiracy” served as a way to sidestep the ethical charge raised by the waging of revolutionary violence (most famously by Kĩama Gĩa Ĩthaka na Wĩyathi or the “Land and Freedom Army”) in a settler-colonial state in three intertwined ways: One, the conspiracy dismissed the political claims of those who participated in the Uprising through delegitimizing its status as an organic movement; two, it avoided engaging with the critiques elevated by the armed struggle through positioning its political thought as the result of brainwashing; and three, it located the agency of the anti-colonial movement outside of its rank-and-file participants. What this very phrase “Mau Mau” designated in its heyday was an anti-systemic militancy in Kenya orchestrated by the string-pulling machinations of a shadowy cabal (variously composed of leading African nationalists, Reds, and/or the “international Jew”). Whatever its particular constitution, according to those like Foot, this nefarious group worked to destabilize the Western order of things by stoking dissent in places where it had not existed before under benevolent colonial governance. The growth in militancy and rejection of prescribed political channels that took shape as Kenya’s anti-colonial sentiment swelled was, thus, taken as evidence of the manufactured nature of the movement; a feature that incentivized narrative structures positioning the Uprising as both an inorganic result of outside agitators exploiting some of the most common organic deficiencies of African subjectivity as constructed in colonial thought (its gullibility, irrationality, and plasticity). As pointed out in an episode on the Mau Mau Uprising by the QAnon Anonymous (QAA) podcast, these ideas were central to articulating how participants in Mau Mau were positioned as having taken to quasi-Satanic practices by being co-opted into a cultish structure dictated by charismatic leadership.

As broached by Caroline Elkins, this framing proved central to producing the rationale for exercising extreme forms of judicial and extrajudicial violence in suppressing the anti-colonial movement in Kenya, resulting in the creation of an elaborate system of British concentration camps and what has been regarded as a genocidal campaign against the Kikuyu. Anchored in the well-trodden political utility of conspiracist argumentation, the “Mau Mau conspiracy” pulled from a common set of elements in this idiosyncratic but remarkably consistent genre—triangulating the stock figures of string-pulling masterminds, their established collaborators within a given mass movement, and the vast populations of “manipulable subjects” they co-direct to nefarious ends. If this triangulation is not endemic to all iterations of conspiracist narratology (and it is not), it remains one of the most common frameworks through which attempts to dismiss the ethical questions raised by anti-systemic movements of all sorts have been pursued. It has been, and remains, a rhetorical structure identifiable in conspiracy theories concerning a range of events throughout history, including the French and Haitian Revolutions, Irish Republicanism, anti-Soviet dissent, environmentalist groups, feminist agitation, and student movements the world over. In each of these conspiracist frameworks, challenges to hegemonic conceptions of Order and economic extractivism share a set of rhetorical figures located in a narrative wherein cabals of shadowy actors conscript easily-manipulated populations and turn them toward nefarious ends. Whether surfacing as slave, “rabble,” political dissident, anti-colonialist, or nationalist, the “manipulable subject” is always only partially an agent of historical action; behind them lurks “the Hidden Hand.” In the case of Mau Mau, the threat of this articulation was relevant not only to dynamics inside the colony, but also to the metropole from which it was ruled.

If the “manipulable subject” was a concrete feature of governance in the colony, the appearance in Britain of colonial conspiracism about Mau Mau also played a key role in justifying British attitudes and actions within the metropole, even in spaces with little direct connection to events in Kenya. Just two months before Foot’s article on Mau Mau appeared in The Star (Johannesburg), residents of the city of Luton in eastern England who picked up their daily newspaper encountered the following headline on its front page: “Africans as Easy Prey: Mau Mau and Communism.”[1] Set alongside advertisements for industrial-grade overalls, reportage on local model train enthusiasts, and investigatory information into the mysterious death of a local woman, the day’s Luton News detailed nothing short of an impending doomsday scenario unfolding in the faraway colony. The August 27th, 1953, article recounts the visit of a Reverend H.G. Rolls to the local Rotary Club three days prior, where he addressed its membership regarding the Uprising in Kenya. According to Rolls (who left no record of ever having travelled to Kenya), African populations, destabilized by the “advent of modernity” on the continent, presented a situation in which: “Easily exploited, the native was prey to those who advocated nationalism of the wrong kind such as Mau Mau, and Communism.” These dual, characteristically-ambiguous threats—Mau Mau and Communism—are co-productive elements in the “Mau Mau conspiracy.” The former delineates examples of African political consciousness untethered from the specific model of constitutional reform acceptable to the British during the 1950s, while the latter serves as a vague shorthand for Cold War-era preoccupations with the nefarious designs of forces behind the Iron Curtain.

This article’s appearance in Luton is not incidental. In the wake of the Second World War, Luton’s proximity to London and relative affordability drew a moderately large influx of African, Caribbean, and South Asian migrants seeking opportunity in the United Kingdom. Those who made their way to Luton landed in a hostile environment. As speculation about immigration being driven by internationalist plots became a normative part of political discourse across the country, conspiracism appeared as a routine and endemic aspect of daily life. Among other things, it is for this reason that towns like Luton featured conspiracy theories about Mau Mau alongside advertisements for sandwich spread and coveralls aimed at a historically white working-class population. The harsh realities of post-war global capitalism and the phenomenon of de-industrialization that reshaped the economic landscape of England made it a place ripe for nativist speculation about who, exactly, was responsible for the reduction in standards of living and job losses. In such a context, it became possible for an uprising in Kenya that sought the overthrow of colonial rule and the assertion of the fundamental rights of African people to feel suddenly much closer to home. In conjunction with the ever-present threat represented by populations of “manipulable subjects,” conspiracist myths of Mau Mau worked to link the collapse of the British empire to apocalyptic visions of life under Communism and, as such, expresses the destabilizing anxieties surrounding decolonization and the possibility of Soviet victory in the developing Cold War.

Here, we see how the “manipulable subject” catalyzes a demos that generates the gravity of “the Cabal’s” threat to dismantling the status quo. This rhetorical strategy is linked to the purported existence of an affective environment alleged to produce psycho-socially destabilized and, thus, easily exploited populations who are perpetually susceptible to radicalization. Put otherwise: What enables the conspiracy to establish successful control over manipulable populations is the psycho-anthropological turmoil they experience as populations who live, as claimed by Foot, “largely through fear,” despair, anxiety, desperation, and illogic. Positioned contra objectivism, the “manipulable subject” is always in some manner insufficiently right-thinking and exceedingly detached from reason. It is a rhetorical effect, as Frida Beckman writes, of the Western subject’s drive to reify itself by “constructing borders against the potentially ‘engulfing otherness’ of growing masses of poor people, against colonial subjects, against the nonhuman.” While the bloodthirsty Mau Mau feared by mid-twentieth-century colonial apologists and the unthinking sheeple lambasted by contemporary conspiracists might harbor different (and often racialized) roles in specific conspiracy theories, they are both alleged to share an imputed condition of gullibility and a general capacity to be bent toward the destruction of the West. Conspiracism in this vein takes shape in what Charisse Burden-Stelly identifies as the “Black Scare/Red Scare Longue Durée” problem-space in Western capitalism that articulates the twin threats of race and progressivism in the past and present.

***

It has now been more than seventy years since the phrase “Mau Mau” began circulating across the world as an icon of violent African rebellion against colonialism. The threat to the racial order that it represented—one that struck at the foundation of the post-war global political economy—generated concerns with the Uprising that traversed political orientations, visions of African futurity, and forms of cultural production. Alongside the assertion of Black freedom from white domination that characterized solidaristic or even quasi-messianic readings of Mau Mau, sat reactionary attempts to dismiss the rebellion as the unleashing of latent savage impulses and the absence of a coherent political program on the part of those who formed the grassroots movement. The impulse to “demystify” Mau Mau in much of the historical literature on Mau Mau (that is, to disprove colonial renderings of its demonic nature and lack of political vision) has tended to obscure the work done by its global embeddedness in conspiracist narratives and understandings of African decolonization. If (pace Foot’s prediction that opens this essay) the “Mau Mau conspiracy” failed as a project of militant decolonization in Kenya, it succeeded as a composite of existing conspiracist and racist tropes assembled to discredit anticolonial resistance, offer scapegoats for the economic disarray brought about by the failure of empire, and entrench colonial paranoia in the postcolonial metropole.

[1] “Africans as Easy Prey: Mau Mau and Communism,” The Luton News, 27 August 1953. Accessed via the British Newspaper Archive.

Dr. Christian Alvarado is a Lecturer in Humanities at San José State University. He earned his PhD in the History of Consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz. An interdisciplinary scholar of African Studies, Alvarado’s work has been published in History in Africa, the Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, and Kritika Kultura (among other venues).

Edited by Tomi Onabanjo.

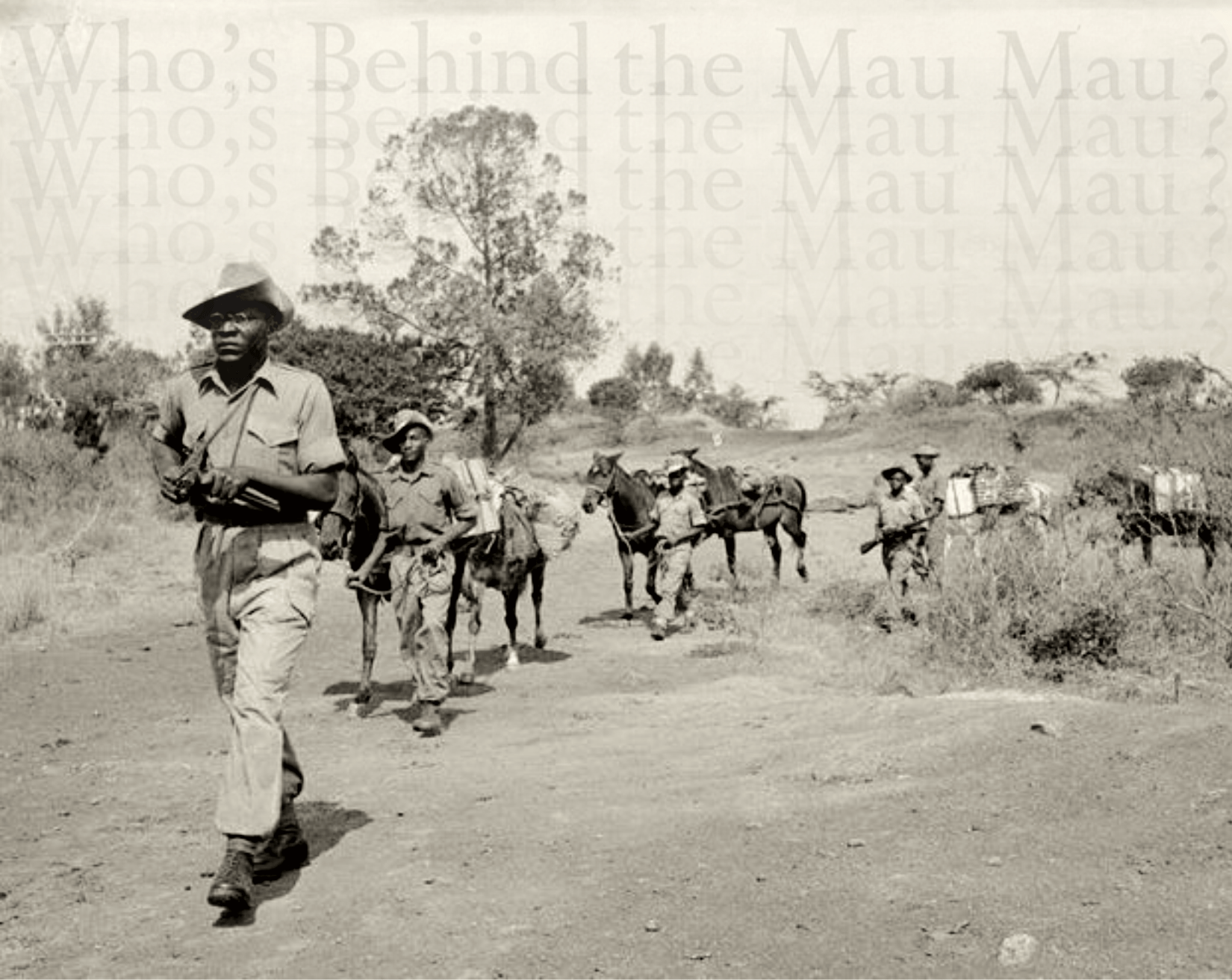

Featured image: Digital montage of the photograph “Troops of the King’s African Rifles carry supplies while on watch for Mau Mau fighters” (Wikimedia Commons) taken between 1952 and 1956 by the British Ministry of Defense, overlaid with the headline of an article (“Who’s Behind the Mau Mau?”) written by Fenner Brockway and published in the February 27th, 1953 issue of the Tribune.