From the burning flames of effigies of Guy Fawkes, ignited and ashy annual reminders to keep in line or be immortalised into history as an enemy of Great Britannia, to the burning of sugared plantations in the Caribbean causing panicked uproars in British Parliament, flames and fury transforming itself into jubilant celebration is an evolution that is no stranger to the United Kingdom.

These are the roots of Carnival as we know it.

What is the oldest carnival in the UK?

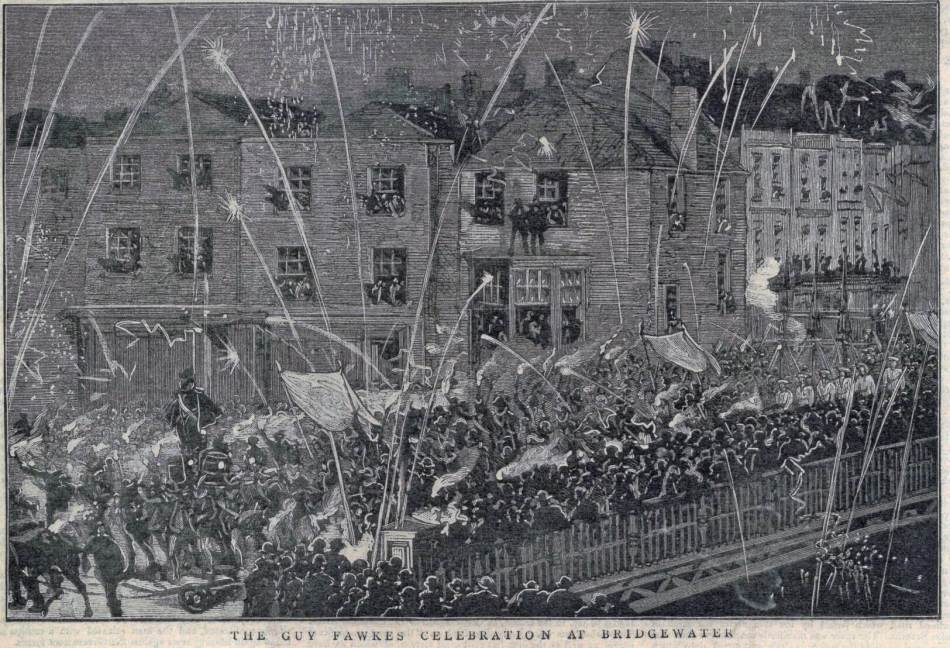

Many may know of Bridgwater Carnival, proudly stating its beginnings as far back as 1605, and said to be Britain’s oldest Carnival. Its fiery festivities inspired the illuminated Carnival celebrations across Great Britain.

A fundamentally Protestant region, Bridgwater jumped at the opportunity to celebrate the demise of Fawkes’ Catholic aspirations to blow up the Parliament in protest against the then King James I.

There are parallels between Bridgwater and Bridgetown, Barbados. Just a few short months after Fawkes was hanged, drawn, and quartered in 1606, the Caribbean Island was landed by the young James Drax, who built his empire on enslaving hundreds of African lives.

Britain’s first Caribbean colony swiftly banned all forms of African music, instruments, and dance. Yet these customs survived, culminating in what we know today as ‘Crop Over’ or ‘the Grand Kadooment’ in Barbados – a yearly explosion of glitter and glamour on the streets cradled by old sugar cane plantations.

While Carnivals like Bridgwater grew and grew, so did the British palettes for all things sweet, leading to an economic boom that culminated in millions of African souls living and dying on Caribbean soil weaved tightly by the roots of sugar cane.

Amongst the growing innovations of wine gums and chocolate drops sold at passing carnival fairs and celebrations, sugared lips in towns and villages sang in jubilant chorus ‘God Save the King or Queen’, whilst Africans sang in whispers in the cane fields or absconded into wild unchartered Caribbean forests to have a moment’s respite to play their forbidden drums in secret.

Carnival merrymaking and festivities

Yet, going even further back into the history of what Carnival is from the perspective of Britain, Europe, and also the Caribbean and South America (when referring to carnivals like Brazil), we must see Carnival as a human demand for the joys of life.

Be it the joys of life’s indulgences controlled by church and society – sex, alcohol, foods seen as sinful – or the fundamental human right to freedom and autonomy over one’s own life, Carnival is a demand for freedom.

We can find records of celebration dating back to 1226 for Shrove Tuesday in Great Britain – the Tuesday before the 40 days and nights of abstinence from the pleasures of life, a nod of acknowledgement to Jesus Christ’s sacrificial walk about in the desert.

Known also as ‘Fat Tuesday’, it was the day of consumption of all the fats in the household before the 40 days of sacrifice. Music, jubilation, and a last grab for joy were the modus operandi across Christian homes in Europe and the UK.

The transference of festivities was evident on Caribbean plantations from as early as the 1500s, when Columbus’ protégées bore witness to their enslaved cargo taking the holiday period as an opportunity to engage in their own Black celebration.

Yet, one of the pinnacle moments that would have lit the spark of the largest carnival we know in the UK – Notting Hill Carnival – began many centuries before the first steel pan hit the streets of West London. In 1783, as France’s revolution was in full bloom, hundreds of Catholic French people relocated to Trinidad and settled in neighbouring islands.

Tied by Catholic allegiance, they swore loyalty to the Spanish crown as they trembled under the weight of letters carrying the news of yet another beheading of their allies in France, Martinique, Saint Lucia, and Guadeloupe.

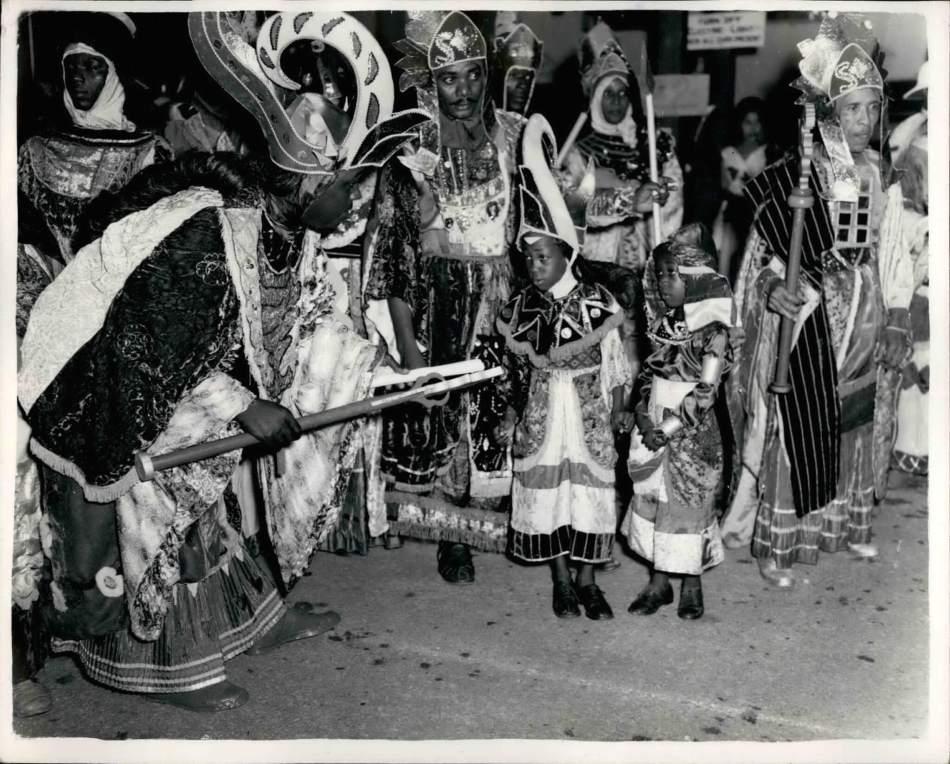

These Catholic plantation owners celebrated pre-lent in magnificent masquerade, elaborate balls where their enslaved African and ‘mulatto’ labourers bore witness to all its splendour. And as their ancestors had done on Columbus’s Spanish colonies, they capitalised on the distraction of their captors to remind themselves of their lost identities and created a carnival of their own.

Subverting European custom, introducing parody and satire, as they too frolicked in the revelry of resistance – a refusal to let go of who they really were.

Regal celebrations and Carnival prohibition

Fast forward several centuries to 1887, when vibrant celebrations of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee were dotted around the nation, and the Isle of Wight took the lead with a parade to celebrate the monarch.

Referred to as “A Rather Bewildering Spectacle” by the County Press, its precedence encouraged its return the following year, and for it to be dubbed ‘Isle of Wight Carnival’.

Yet, across the Atlantic this very same year, British law enforced something else new – a law banning all forms of African percussion in the islands of Trinidad and Tobago, deeming the practice ‘demonic’ and riot-inciting.

Despite 1888 being half a century since the Abolition of Slavery, colonial oppressive forces still denied thousands the right to hold festive occasions. So, while carnival celebrations spread across Yarmouth, St Helens, Newport, and other towns and villages, British laws spread across the Caribbean banning any forms of parade, percussion, or masquerade.

When was the steel drum invented?

A new variant of percussion was born in the quiet lull of the Second World War, where the world rationed out livelihoods in stamp books and tiny portions. Under the heaviness of the colonial laws, innovation broke through in the form of drums.

Trinidad and Tobago, a nation with a growing petroleum economy, was littered with abandoned oil drums. When life was brought to a wartime standstill, musicians experimented until they invented the only new instrument to be born in the 20th century: the steel drum.

Also known lovingly as ‘steel pan’ or simply ‘pan’ by most Caribbean communities, the discarded oil drums became the voice of a community that experienced generations of cultural suppression.

Coming out of working-class neighbourhoods, the steel pan was perfectly paired with the plight for the right to parade the streets, and so with that, the English-speaking Caribbean witnessed a new resurgence of a cultural practice that survived centuries of laws to stop it.

After the Second World War ended in 1945, many thousands of Caribbean people from the then British colonies migrated to what was affectionately called ‘The Mother Country’ to assist in Britain’s effort to rebuild after the war’s devastation. While the Caribbean experienced a brain drain of some of the most dedicated minds, the UK experienced an incredible cultural injection.

Thousands of Caribbean arrivals did not receive the warm motherly embrace they were told they would, with a backlash from racist groups like the National Front and some Teddy Boys leading to losses of Black life, while groups of thugs and some police went on targeted hunts to assault Black British citizens in the dark of night or brazenly in broad daylight.

And much like how Carnival began in the Caribbean as a march for freedom, an unwavering desire for the basic human right to joy, so it continued in the UK with the birth of Leeds Carnival and Notting Hill Carnival.

When was the first Notting Hill Carnival?

With the brilliant activist Claudia Jones hailing from Trinidad and Tobago, banished from her homeland and the USA for her community work, championing the rights of Black and Brown people, she found herself traversing the streets of Vauxhall in the 1950s.

Bearing witness to yet another race war as the post-war influx of Black faces, heads down and voices lowered as they worked dutifully to have a place in the land of their ‘Mother’, Jones couldn’t stand to see yet another Black face bloodied by the fists of some well-dressed Teddy Boys or Bobbies.

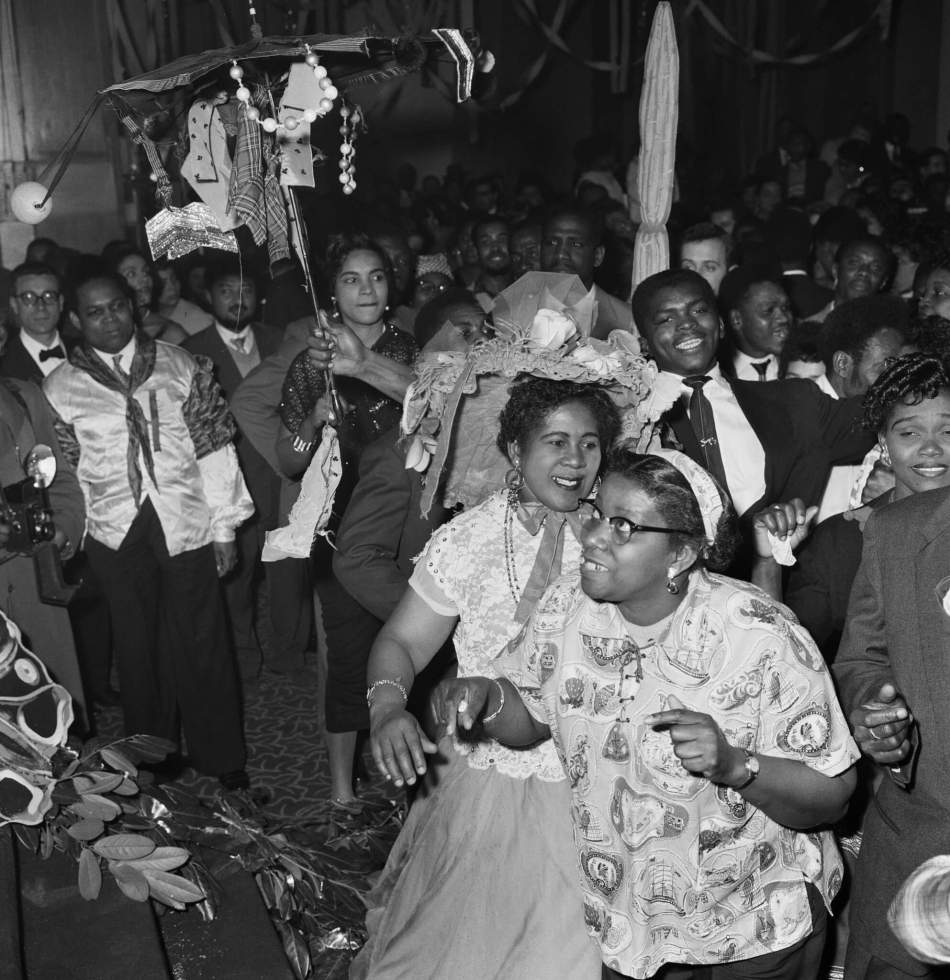

Beginning as an indoor carnival in King’s Cross, London, to allow a safe space for Caribbean people to sing and dance together, a place where familiarity was a rarity, Claudia Jones began the first Caribbean Carnival in the UK.

Knowing Caribbean Carnival’s political roots, she used the event as an opportunity to raise funds to pay for the legal fees for those affected by the race riots, both Black and Brown Caribbean people and white British who stood as allies against racism.

Communities like Leeds brought to the streets for the first time a processioned Caribbean Carnival in 1967, often forgotten under the multi-million-pound enterprise that is Notting Hill Carnival today.

Notting Hill’s streets became the epicentre of pageantry and parade after community activist Rhaune Lasslett began the Notting Hill Fayre in 1966, inviting marginalised community groups from the predominantly migrant West London neighbourhood.

Whilst the Irish, Russians, Ukrainians and Poles created festive treats and games, a group of Caribbean steel pan players did what they always knew – they took to the streets in procession. Once again, they put their culture and identity to the forefront, a reclamation of space, a demand for the right to equality. Carnival became a transference of marches for freedom from one colonial space to another.

Carnivals within the UK draw on many parallels from Catholic and other Christian rituals, parades, and pageantry. The foundations of British Carnival stem from celebrations of monarchical legacies, often oppressive ones, stamping out the voices of many disenfranchised. Those from the Caribbean are founded on a fundamental right: human equality.

About the author

Fiona Compton is a St Lucian filmmaker, historian, and cultural ambassador, and the founder of ‘Know Your Caribbean’, the leading platform for Caribbean history and culture. Through vibrant storytelling, educational resources, and visual art, she amplifies the Caribbean’s rich legacy, challenges colonial narratives, and inspires pride across the global Caribbean diaspora and beyond.

Further reading