The world’s first standard gauge, steam-hauled public railway, the Stockton and Darlington, opened on 27 September 1825, connecting places, people, and communities. It went on to transform the world.

A railway revolution swept Britain in the 19th century, changing the country forever. A predominantly agricultural society had metamorphosed into an urbanised industrial superpower.

2025 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of the modern railway. Railway 200 is a year-long, nationwide campaign to celebrate 200 years of the modern railway.

England’s spectacular historic environment includes numerous sites and places related to the story of rail.

The Railway 200 website includes a timeline highlighting some of the significant moments that defined the railway. Here, we will explore some of the fascinating sites which illustrate that timeline.

When was the first steam train invented?

While the Stockton and Darlington is generally accepted as the world’s first public railway to use steam locomotives, there were many earlier railways, some also public, some using steam power. Guided systems of transport, horse-drawn or man-worked, had developed across the mining areas of North East England throughout the 18th century.

The magnificent Grade I listed Causey Arch still stands today and is a monument to those pioneering wagonways. It was built in 1727 and is considered to be the earliest surviving railway bridge in the world.

These days, it carries a footpath alongside the Tanfield Railway, a heritage line. The Tanfield Railway itself runs on the formation of an early wagonway and, as such, has a credible claim to being the world’s oldest operating railway.

These wagonways were all horse-powered, however. Early experiments with steam took place in the early 19th century. Cornish engineer Richard Trevithick designed the Pen-y-Darren locomotive in 1804, which was used to haul coal on the Merthyr tramroad (now a scheduled monument) in Wales.

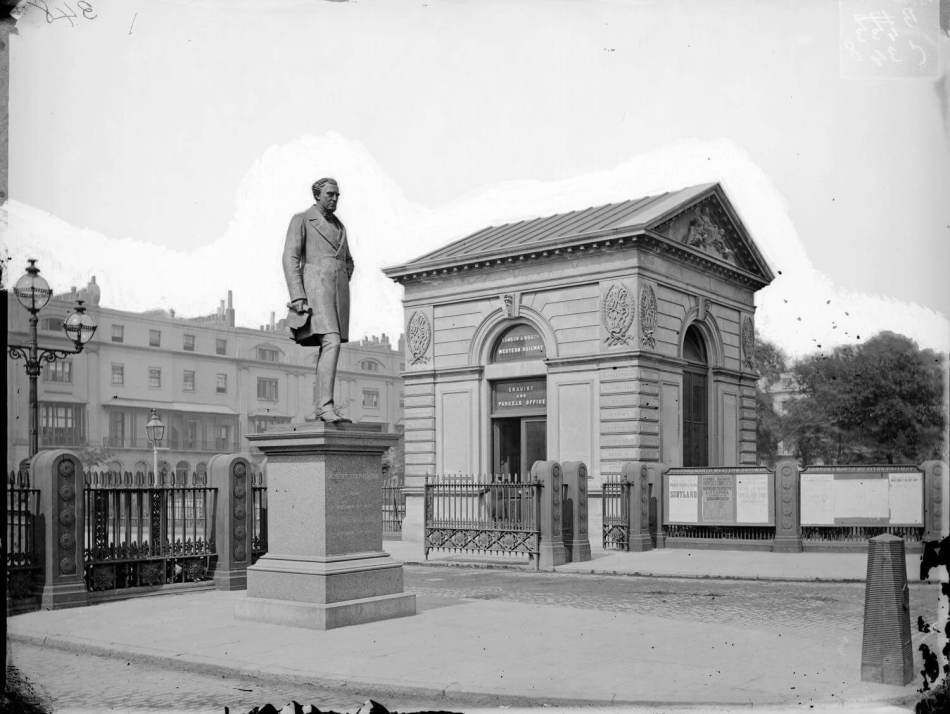

Trevithick then designed a locomotive to haul passengers in 1808. The catch-me-who-can ran on a circular track in London’s Euston Square to attract investors. While he failed to win investors, Euston Square later became the terminus of London’s first inter-city railway, the London and Birmingham, in 1838.

Today, that innovation continues, with Euston Station being rebuilt as the terminus of HS2. The West Midlands end of HS2 will also have a strong heritage connection, incorporating the Grade I listed 1838 Birmingham terminus building.

When was the first passenger train invented?

On 27 September 1825, the 26-mile Stockton and Darlington Railway opened with a special train of over 30 coal wagons and one passenger coach (‘Experiment’), hauled by a steam locomotive. Starting near Shildon, north west of Darlington, it made several stops before finishing at Stockton. This train carried over 500 passengers.

However, early regular passenger services on the line were single coaches hauled by horses. The limited number of available locomotives were reserved for heavy coal trains. Regular steam-hauled passenger trains on the Stockton and Darlington started in 1833, after such services had been running on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway for 3 years.

Much of the 1825 main line remains part of the national rail network, including the Skerne Bridge, built in early 1825 and subsequently strengthened.

Darlington North Road Station was built a few years later and is situated just to the west of the bridge. The station has recently been restored as part of Darlington’s Railway Heritage Quarter and Hopetown, a new railway heritage attraction.

George Stephenson was the engineer for the Stockton and Darlington Railway and, with his son, Robert, built the railway’s first steam engine, Locomotion No 1, which still survives and can be seen at Locomotion in Shildon.

A few years later, Robert designed and built the Rocket locomotive (also known as ‘Stephenson’s Rocket’) in their Newcastle works, which still exists today and is the world’s first purpose-built locomotive factory.

The Rocket was built for the Rainhill trials, a competition amongst engineers to find suitable machines to operate the Liverpool-Manchester Railway, the world’s first inter-city line, in 1830 (although neither Liverpool or Manchester were considered cities at this point).

Happily, the Rocket also still exists and can be seen in the National Railway Museum in York.

In 1825, the concept of the railway station had yet to evolve and none had been built for the opening of the line.

The Grade II* listed Heighington and Aycliffe Station, built in 1826 as a tavern to supervise a coal depot, was fulfilling the functions of a railway station by 1828 and lays claim to being the earliest railway station in the world.

However, it did not take long for stations to develop a form we still recognise today, based on a pavilion with canopies and platforms. Perhaps the earliest surviving ‘modern’ station is the Grade II listed Micheldever, on the London and Southampton Railway of 1840.

The development of railway towns

As railways developed, entire railway towns emerged to house the staff required to build and operate the railways.

Swindon in Wiltshire is a good example of an early railway town. The market town already existed, but Isambard Kingdom Brunel built a ‘New Swindon’ to house the staff of the Great Western Railway alongside it.

His Grade II listed railway workers’ cottages are part of one of our Heritage Action Zones, designed to capitalise on Swindon’s railway heritage to foster economic, social and cultural enterprise.

Alongside Stephenson, Brunel figures strongly in the history of early inter-city railways. Not all his ideas were a success, however. While his line between London, Bristol, and slightly later, Exeter, were engineered with minimal gradients that permit very high speed, he had a different plan for the undulating terrain between Exeter and Plymouth.

It was envisaged that trains would run on a vacuum system. A stationary engine would pressurise a tube, and a vehicle would carry a piston travelling in the tube. You can see a section of the original tube at Didcot Railway Centre.

Problems with sealing the slot to enable the piston to enter the tube led to the project’s abandonment, but a Grade I listed engine house at Starcross survives as a monument to the failure. The building is currently on our Heritage at Risk Register, and we are advising on solutions.

Another Heritage Action Zone in Lancaster also has a railway connection. Numbers 4 and 5 Stonewell, recently restored using our grant funding, were the home of Thomas Edmundson, inventor of the pre-printed railway ticket. Tickets were numbered and validated by a date-stamping process, allowing simple accounting.

All change please

The railways brought about monumental changes to society, expanding the possibilities for travel, work and trade. Before the arrival of the railways, time was typically determined in each town by a local sundial, resulting in variations in local time.

Local time in Bristol, for example, was 11 minutes behind local time in London. The Great Western Railway first applied a standardised time arrangement, but railway time quickly became adopted as the default. In Bristol, the clock on the Grade I listed Corn Exchange still has 2 minute hands: one for railway time, and one for Bristol time.

The railway was a driving force behind societal change, and this is reflected in J.M.W. Turner’s famous painting ‘Rain, Steam and Speed’, which depicts a Great Western Railway (GWR) train rushing across Maidenhead Bridge, now a Grade I listed structure.

However, many view the painting as an allegory for societal change, as the train hurtles towards an industrial future.

The boom of the seaside holiday

Though travel was generally divided into 3 classes, the railways were a great leveller in terms of mobility. Holidays by rail experienced significant growth throughout the 19th century, with entire resorts being created in seaside areas.

Scarborough in North Yorkshire, for example, expanded massively after the arrival of a railway from York in 1845, and its Grade II listed station remains today.

Bournemouth in Dorset did not exist before the railways, although its grand, continental-style station dates from 1885, 50 years after the town’s first villas.

Weston-super-Mare in Somerset was also a product of the railways. The size of the staircases at its Grade II listed station shows the vast size of the crowds that would once rush through, although the adjacent excursion platforms are long gone.

Green signals

One interesting survivor in Weston-super-Mare is what is thought to be the country’s earliest surviving signal box. A modest little building, now disused and slightly forlorn in the corner of a contractor’s compound, it was built in 1866 and predates the station by 10 years or so.

Signalling improvements nationwide brought considerable safety benefits, and today, train travel remains one of the safest forms of travel.

Very early railways were controlled by ‘railway policemen’ using flags, but mechanical signal boxes needed to be developed to protect the safety of trains. The invention of the railway telegraph allowed messages to be sent ahead of trains.

In 1845, a murder suspect boarded a train at West Drayton, but the electric telegraph enabled him to be apprehended on arrival at Paddington Station. The original Paddington Station was located slightly west of the magnificent present-day station, now a Grade I listed building, which opened around 10 years later in 1854.

Anything off the trolley?

As train travel became the norm in the 19th century, passengers began to demand both comfort and speed. GWR pioneered the railway buffet, opening the first-ever railway refreshment room at Swindon station.

All trains stopped here for 10 minutes, but this prevented the speeding up of trains. GWR was sued by the buffet landlord when Exeter services began running non-stop in 1845.

The Grade II listed station buildings at Swindon’s London-bound platform, which contained a buffet, still survive.

Electric trains: Into the 20th century

Just as steam had supplanted the horse at the start of the 19th century, in the late Victorian period, a new form of traction began to emerge – electric. The first electric railway in the country was a short, narrow-gauge passenger line along Brighton Beach, and fantastically, it still runs today.

Passengers can travel on the Volks Railway in the summer months. Although none of its original buildings now exist, the Grade II* listed cast-iron arcade at Madeira Terrace still forms the backdrop to the railway and is currently being restored using our grant aid.

Early electric trains also offered a solution in central London. While steam engines could be used on underground railways constructed just beneath the street using cut-and-cover tunnels with frequent vents, it would be impossible to operate steam in deep-level tunnels.

The City and South London railway was the world’s first electric metro and still runs today as London Underground’s Northern Line. Grade II Listed Kennington Station is an example of one of the earliest deep-level tube stations.

The rapid success of the underground led to the development of electric solutions to similar problems, as seen with the use of steam trains elsewhere. The railway tunnel under the Mersey in Liverpool opened in 1886 (one of its pumping stations is Grade II listed), but steep gradients and frequent services meant the tunnel was often filled with smoke.

The line was electrified and transformed: whitewashed, electrically lit stations presented a modern and futuristic image to the Edwardian passenger.

Travelling into the modern age

The public’s perception of electrification provided the railways with an opportunity to create a new, modern image, one far removed from the smoking and clanking world of steam.

The Southern Railway adopted electrification following successful experiments by its predecessors, the London and South Western Railway and the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway. The Southern electrified at pace, with striking new stations in an Art Deco style. Many of these remain today, but the crown jewel is probably Grade II listed Surbiton.

Surbiton was designed by the Southern Railway’s in-house architect team under James Robb Scott. Robb-Scott is something of an enigma. He could turn his hand to a wide range of styles, from the art deco of Surbiton to the Edwardian Baroque of Waterloo’s Victory Arch via the Neo-Georgian Ramsgate.

However, despite his work in transforming the image of travel in the early 20th century, he remains relatively little-known as an architect.

Protecting our rail heritage

Electrification remains one of the most efficient forms of propulsion on today’s rail network. We work alongside Network Rail to ensure that Victorian infrastructure is sensitively adapted as more lines are electrified, helping to ensure this can still perform the job it was designed for all those years ago.

The railway is not a museum; its primary purpose remains to carry passengers and freight. However, 200 years of public railways have left a remarkable architectural legacy, one that continues to evolve and develop.

In a few years’ time, in an almost full circle moment, HS2 trains will leave from Euston, where Trevithick demonstrated his steam locomotive.

Written by Simon Hickman

Discover your historic local heritage

Hidden local histories are all around us. Find a place near you on the Local Heritage Hub.

Further reading