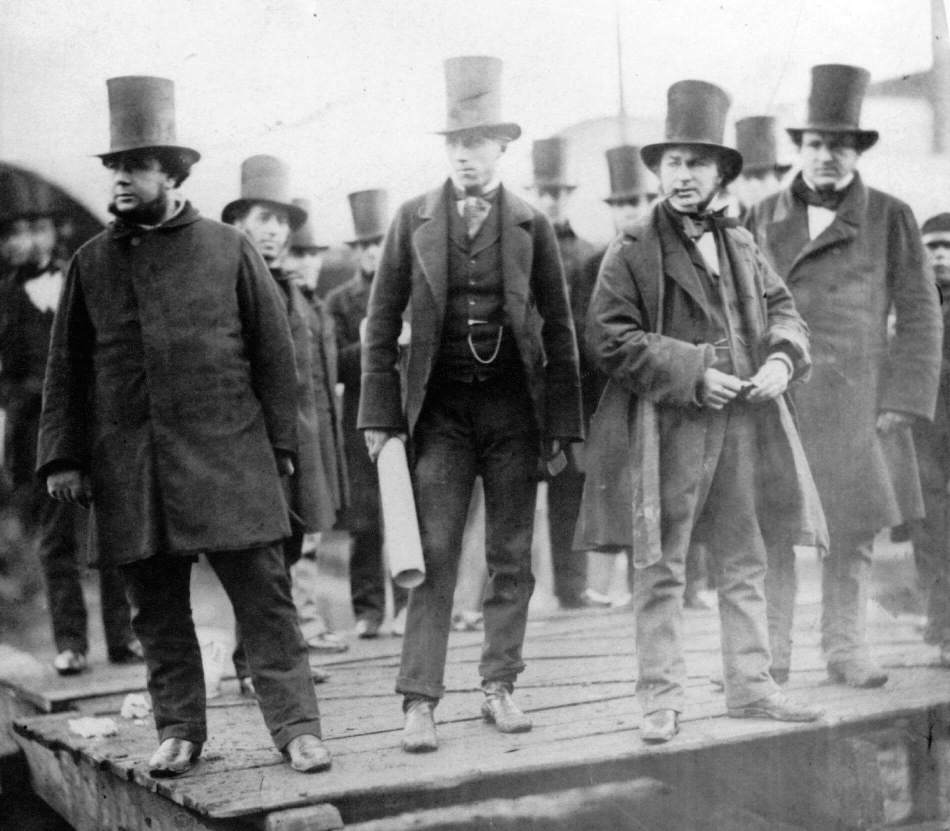

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806 to 1859) was one of the giants of the Industrial Revolution.

His originality of thought, extraordinary vision, and risk-taking ushered out the old world of sailing ships and horse-drawn transport. He pioneered a new age, revolutionising engineering and transport with ground-breaking designs for railways, steamships, bridges, tunnels and docks.

Here, we look at some of his greatest achievements, many of which remain in use today.

When was Isambard Kingdom Brunel born?

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born on 9 April 1806 in Portsmouth, Hampshire. He was the only son of British-based French-émigré engineer Marc Isambard Brunel (1769 to 1849), a prolific and renowned inventor, and Sophia Kingdom.

He taught his son drawing, geometry, and the basic principles of engineering from the age of 4, as well as helping him become fluent in French.

Marc wanted his son to be an engineer and sent him to France at 14 for technical schooling, which was unavailable in Britain.

Isambard returned to England in 1822 to work in his father’s office. This marked the start of the extraordinary career of this diminutive genius.

What structures and bridges did Isambard Kingdom Brunel build?

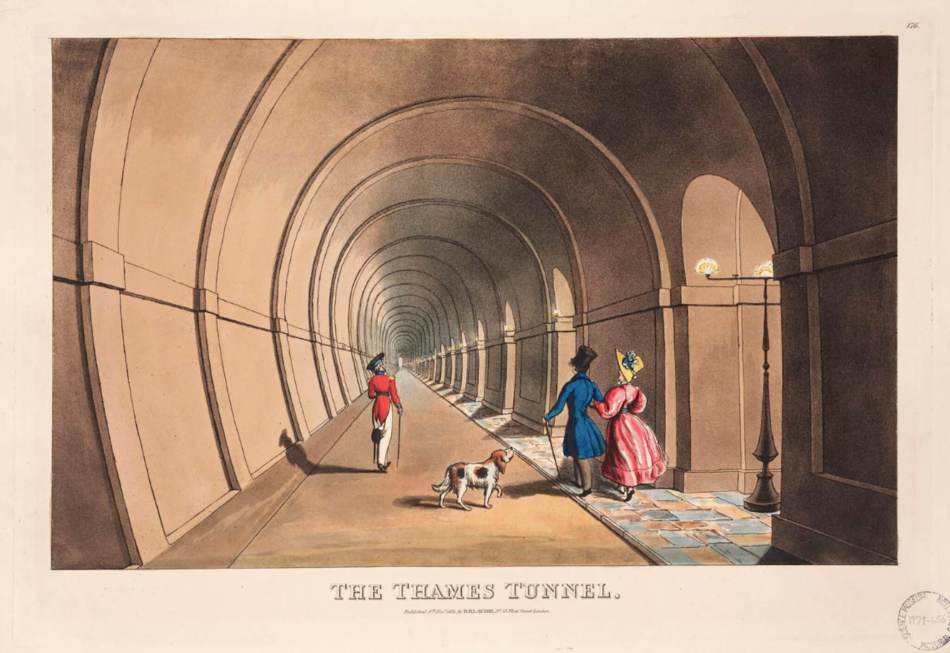

1. Thames Tunnel, London

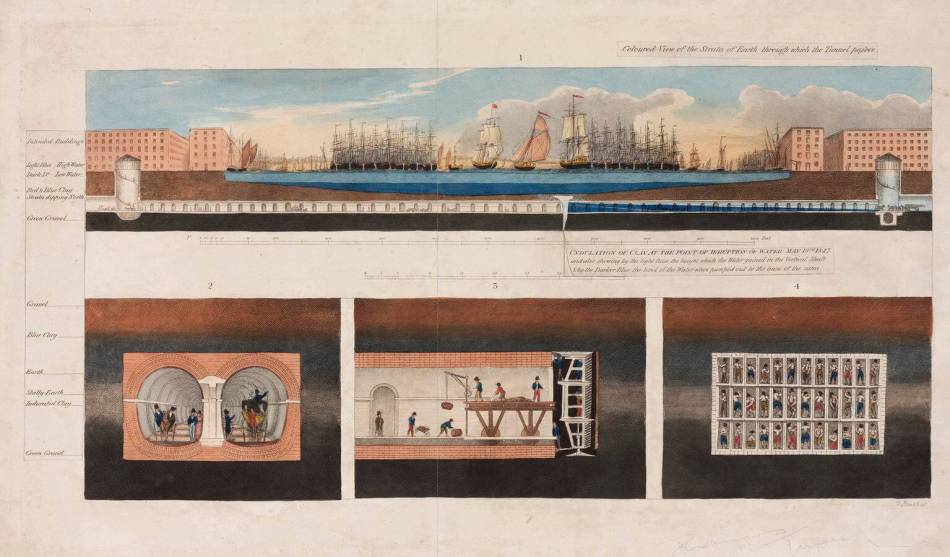

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, 2 projects were underway to build a tunnel under the River Thames to alleviate the traffic jams on London Bridge, the only downstream bridge in the capital at that time.

The projects failed due to flooding and the dangerous instability of the area’s clay, mud and quicksand. The concept of the tunnel was deemed impossible.

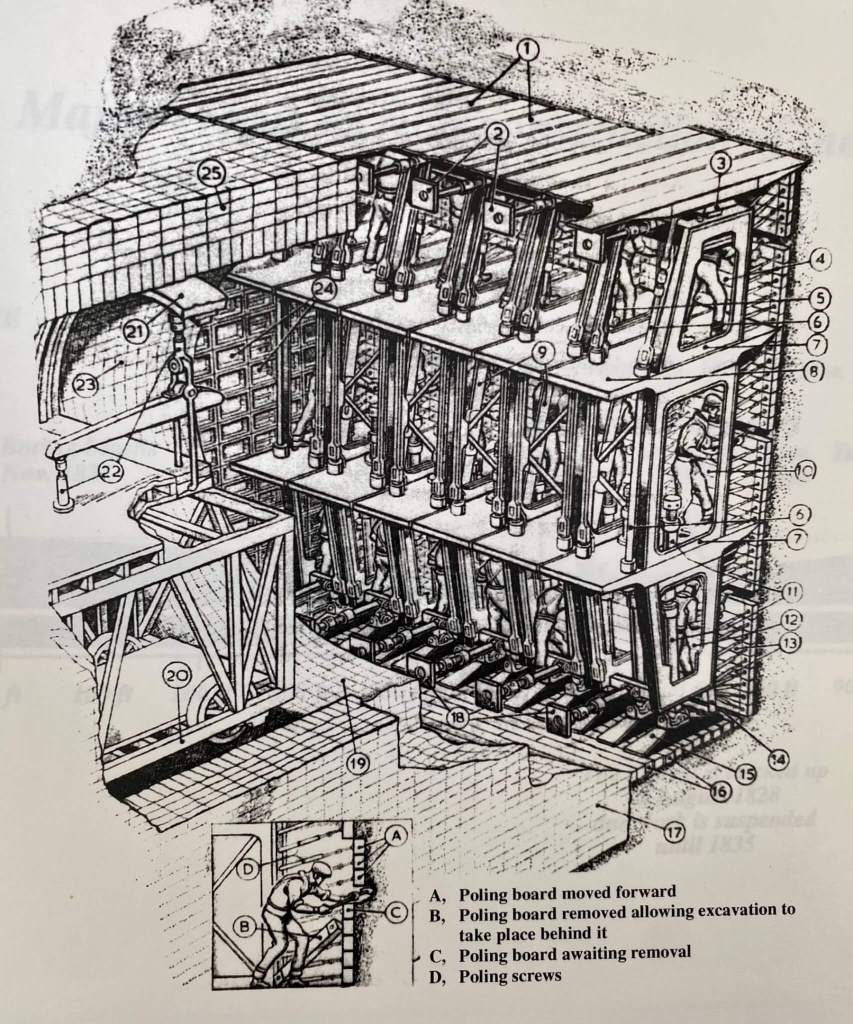

However, Isambard’s father took up the challenge, patenting a tunnelling shield and creating a new tunnel plan in 1823. Private investors funded the project, which began 2 years later, with Isambard joining his father as Resident Engineer in 1827.

The excavation was extremely hazardous. There were fires, methane and hydrogen gas leaks, and sudden flooding. Workers drowned, and Isambard himself was revived after being pulled unconscious from a flood.

The Thames Tunnel finally opened on 25 March 1843 after 20 years of delays, primarily due to flooding but also due to continuing financial problems.

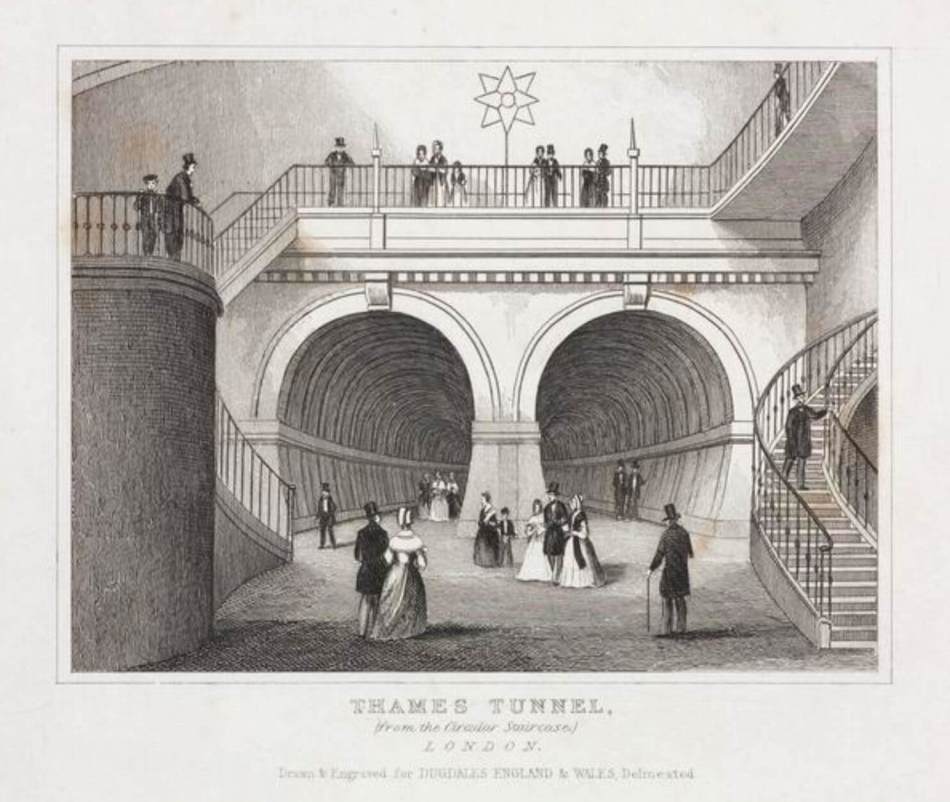

The Brunels’ structure was the first subaqueous tunnel in the world. This was a spectacular triumph of engineering. But it was a failure financially.

Initially intended for horse-drawn vehicles to alleviate traffic across the river, extending the entrance shafts to accommodate them proved too prohibitively expensive. The tunnel instead became a major Victorian tourist attraction.

An estimated 2 million people a year paid 1 penny to visit.

Smart shops selling fancy goods were sited within the arches between the 2 tunnels. They were decorated with marble counters, gilded shelves and mirrors, and brightly lit with gas burners.

The tunnel’s popularity as a tourist destination gradually waned, and it became the haunt of sex workers and robbers.

In 1865, the East London Railway Company bought it and converted it into a railway tunnel. The first steam trains ran through it in 1869. Later, it became part of the London Underground’s East London line. In 2010, it was repurposed as part of the new London Overground.

2. Clifton Suspension Bridge, Bristol

Following his near-drowning in 1828, and while the Thames Tunnel project was still underway, Isambard was sent to recuperate near Bristol. Here, he heard news of a competition to build what would become the Clifton Suspension Bridge over the deep limestone gorge of the River Avon.

Brunel submitted several designs and eventually, in 1831, was declared the winner. He was just 24.

Brunel’s design was an elegant bridge, with a great tower at either end in the then fashionable Egyptian style surmounted by sphinxes. The bridge crossed the whole gorge at a height of 75 metres in a single 214-metre span, suspended by colossal double chains. It was the longest bridge in the world at that time.

Parts of the bridge were completed in 1842, but funds ran out the following year. Brunel was ordered to suspend the work, and materials were sold off to pay creditors. The towers stood abandoned.

Brunel died in 1859 without completing his bridge. In 1860, as a memorial to him, the Institute of Civil Engineers formed a company to complete the bridge. Several changes were made to Brunel’s original design, including rejecting the Egyptian theme for the towers and adding more chains.

The bridge finally opened on 8 December 1864 and is still used by millions of vehicles a year.

3. The Great Western Railway, London to Bristol

The opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825, the world’s first goods and passenger railway, and later the Liverpool and Manchester Railway with George Stephenson’s engine ‘Rocket’, proved the vast potential of railways in the 19th century.

To compete with the rival port of Liverpool over Atlantic trade, Bristol needed a railway to link it with London.

In 1833, Brunel was appointed Chief Engineer of the Great Western Railway (GWR), previously the Bristol Railway Company.

Brunel surveyed each mile of the GWR London to Bristol route himself on horseback, negotiated with landowners, controlled contracts, and designed most of the route’s buildings and bridges.

However, the route presented Brunel with enormous technical difficulties.

Bridges had to be constructed, such as Maidenhead Bridge over the River Thames in Buckinghamshire and the Royal Albert Bridge spanning the River Tamar between Plymouth, Devon, and Saltash, Cornwall (both Grade I listed).

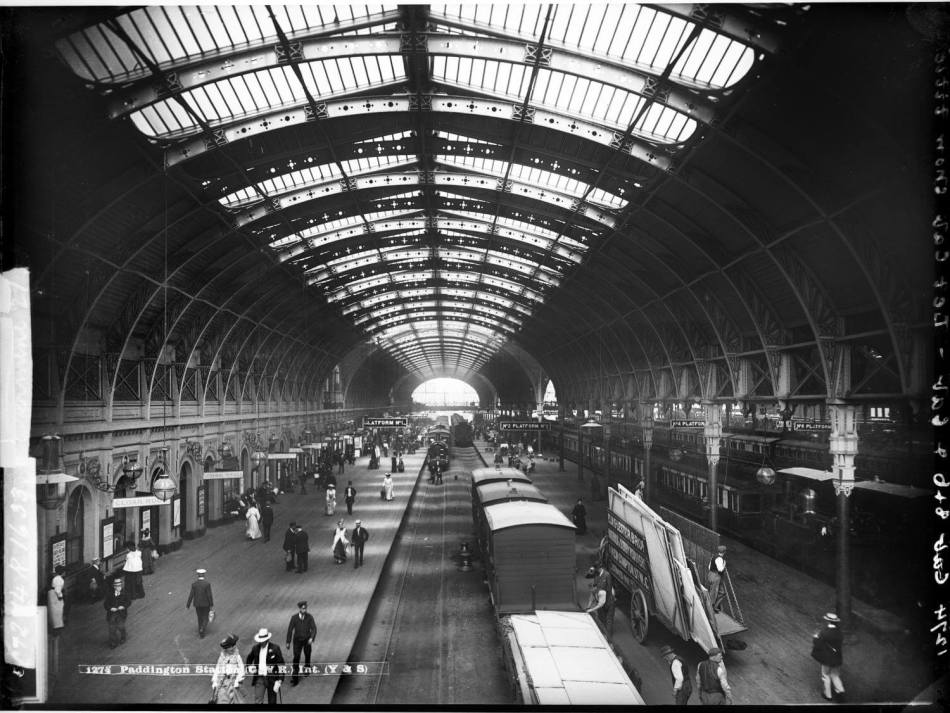

Viaducts, such as the Grade II* listed viaduct in Chippenham, needed to be built, and new stations had to be established all along the route, including the termini of Paddington and Bristol Temple Meads.

An immense team of over 1,000 navvies excavated and constructed the route by hand. 3 viaducts, 4 major bridges, and 7 tunnels were built between the Bath and Bristol section alone.

The first leg from Paddington to Maidenhead opened in 1838. It reached Reading by early 1840 and Swindon by the end of the year.

However, between Bath and Chippenham, Brunel faced one of his greatest engineering challenges: creating a tunnel nearly 3 kilometres long through solid rock.

The Box Tunnel took 3 years to construct. In the final months, around 4,000 workers used 1 tonne of explosives every week to blast through the rock, along with 1 tonne of candles for illumination. 20 million bricks were laid. An estimated 100 workers died during the construction.

When completed in 1841, the Box Tunnel was the longest railway tunnel in the world. In June 1841, the Great Western Railway London to Bristol route finally opened.

In the following years, the growth of the railways boomed across the country. Brunel was the chief engineer for GWR’s expansion. Over 1,200 miles had been built under his design and supervision by his death.

4. Steamships SS Great Western, SS Great Britain and SS Great Eastern

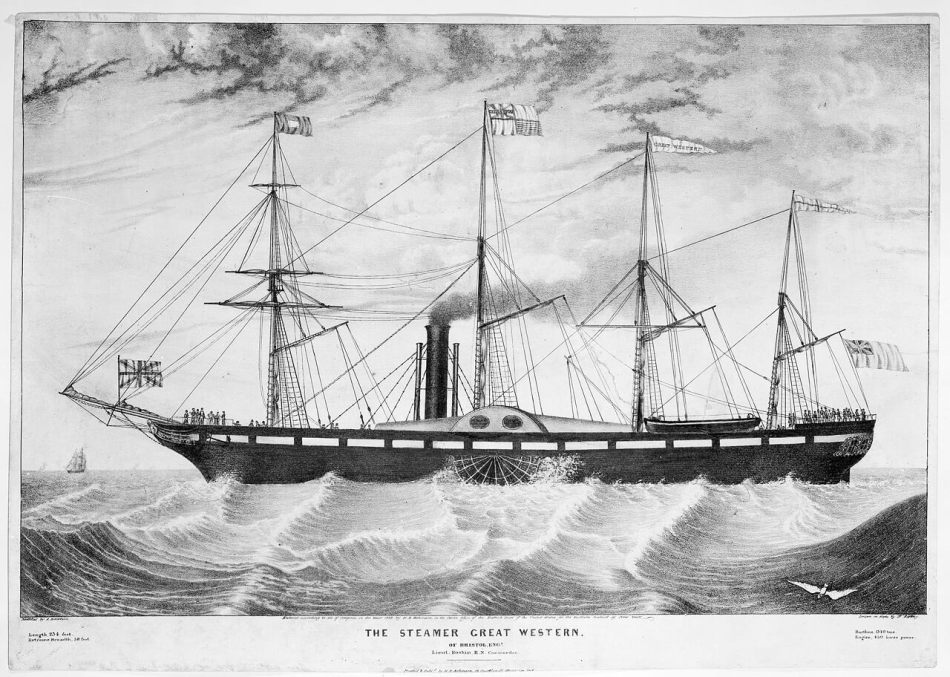

Brunel had a long-term vision of creating transatlantic travel from Bristol to New York. He offered to work for the Great Western Steamship Company for free to test his ideas.

His SS Great Western, then the longest ship in the world, with a hull mostly made of oak, made its maiden 15-day voyage from Bristol to New York on 8 April 1838, proving the viability of commercial transatlantic travel.

Brunel missed the voyage, having been seriously injured in a 6-metre fall during a fire in the engine room.

Convinced that screw propellers were technically superior to paddle wheels, Brunel then designed the SS Great Britain, the first iron-hulled and propeller-driven ship to cross the Atlantic. She made her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York in July 1845 in 14 days.

After several successful journeys, she ran aground in 1846. Sold for salvage and then repaired, she later carried immigrants to Australia before retiring to the Falkland Islands and eventually scuttled there in 1937.

In 1970, the historic ship was raised, towed back to England on a giant barge, and restored as a tourist attraction in her original home of Bristol.

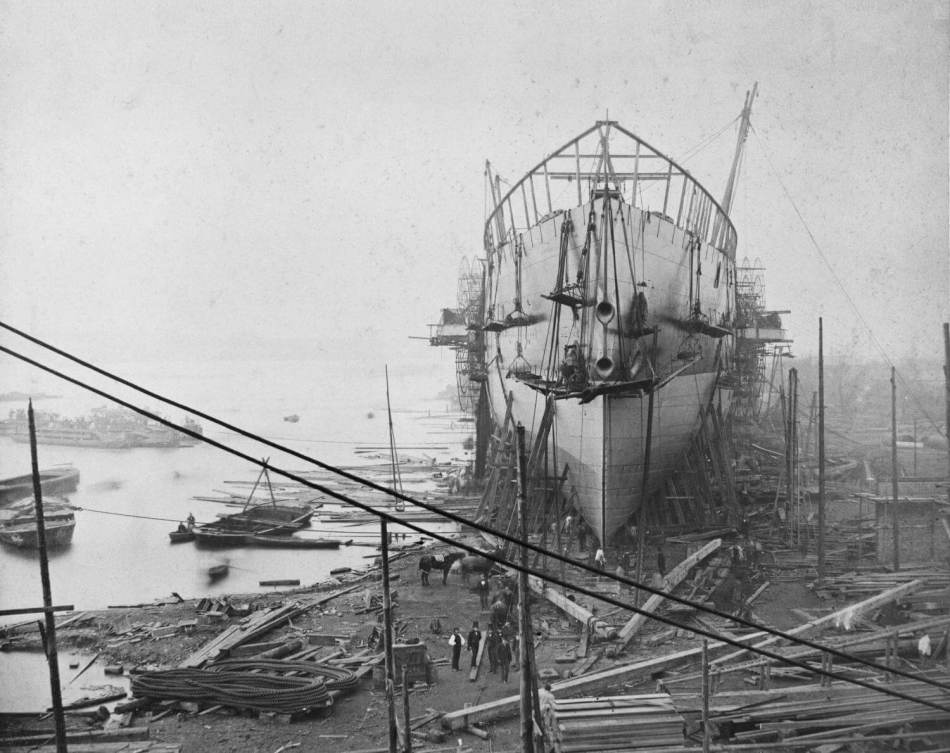

Years ahead of his time, in 1852, Brunel designed and built the enormous SS Great Eastern, 6 times the size of SS Great Britain.

It would be a luxuriously appointed liner for over 4,000 passengers and several thousand tonnes of cargo that could make a non-stop voyage from London to Sydney, Australia.

The ship was over budget, behind schedule and suffered technical problems, but her maiden voyage from London to Holyhead in Wales was scheduled for early September 1859. Brunel, frail and unwell, visited his ship before the launch. He had a stroke on board and was taken home.

A few days later, the SS Great Eastern headed down the River Thames. However, she was wracked by a huge steam explosion near Hastings, killing and injuring members of the crew.

The Great Eastern failed as a passenger liner and lost money. Still, later, it found a significant role as an oceanic cable layer, laying the first transatlantic cable telegraph and enabling communication between Europe and North America.

When did Isambard Kingdom Brunel die?

Brunel, who regularly worked 20 hours a day, smoked 40 cigars daily, and worked on vast projects concurrently, was told about the Great Eastern’s tragedy and died days later on 15 September. He was 53.

Brunel was buried in the family vault with his father, Marc, in Kensal Green Cemetery, London.

He was survived by his wife, Mary, and 3 children: Isambard Junior, Florence Mary, and Henry Marc, who became a successful civil engineer.

A memorial window was erected in Westminster Abbey’s nave in 1868.

Brunel’s lasting legacy

There are many monuments to Brunel, along with many locations bearing his name.

But his enduring legacy is best represented by his railways, bridges, tunnels, viaducts, buildings and docks across the country, many of which were engineering firsts and remain in use today.

Written by Nicky Hughes

Further reading