Tucked away on the corner of Vicar Road in Darfield, an ex-mining village in South Yorkshire, there’s an inconspicuous, volunteer-led museum containing a truly surprising history.

The Maurice Dobson Museum and Heritage Centre is billed as a tribute to Darfield’s industrial and coal-mining past, as well as a place to grab a cup of tea and slab of delicious cake at the in-house café.

These are all accurate descriptors. But some of the most interesting artefacts inside nod to the colourful life of Dobson himself, somewhat of a local legend.

Researcher Stephen Miller was fairly new to Barnsley when he first stepped into the museum, and his expectations were modest. “I assumed that Maurice would be some kind of antiquarian who left behind his collection,” he recalls.

“But then one of the volunteers showed me a couple of shelves dedicated to Maurice himself. There were these amazing photographs of him fully glammed up, wearing a fancy blouse and holding his cigarette.”

These images immediately grabbed Miller, who later spent years pulling together an in-depth oral history project.

Who was Maurice Dobson?

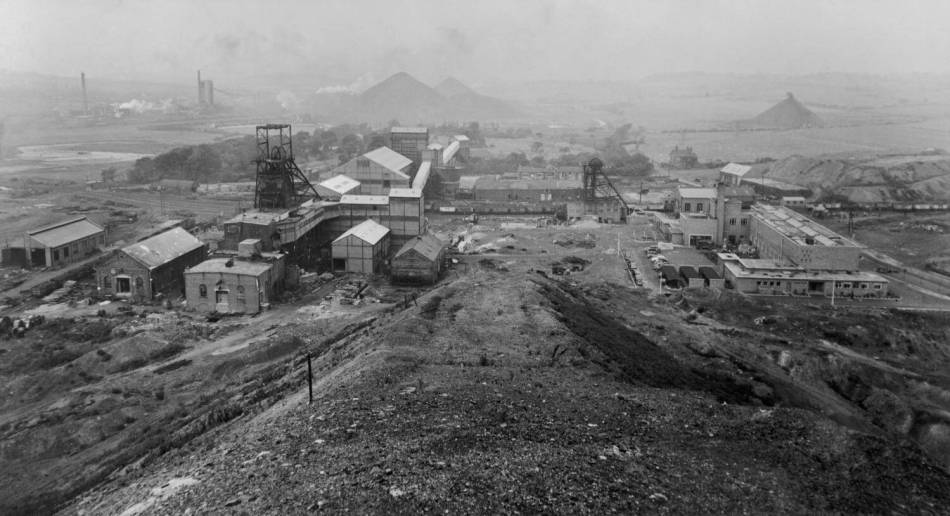

Maurice Dobson was born in 1912 in Low Valley, Wombwell, just a stone’s throw away from Darfield. He was born into a family of miners. “His mum and dad both came from esteemed mining stock,” explains Miller, and he was raised alongside 7 siblings.

Dobson followed in his family’s footsteps at the earliest opportunity and headed down the pits, working as a coal miner before later joining the army. He served during the Second World War (1939 to 1945), spending his time stationed on brutal battlefields across North Africa.

Dobson survived the war and moved back to Darfield in the late 1940s, but he didn’t come alone; he came with his partner, Fred Halliday.

For decades, Dobson and Halliday lived in relative peace as an openly gay couple. They ran a corner shop filled to the brim with cold meats, pantry staples and jars of colourful sweets. Locals recall stepping inside to find Dobson perched on a high stool, dressed in a dapper suit with a cigarette holder in one hand and a parrot on his shoulder. Halliday was comparatively low-key, usually dressed in a brown smock instead.

Clearly, Dobson was charismatic. He’s described by those who knew him as eccentric, divisive and hard as nails. Despite being just over 5 feet tall, he could throw a mean punch. Rumour has it that local pubs treated Dobson as de facto security, nodding discreetly in his direction if troublemakers tried to start fights.

In recent years, local newspapers have retold the story of Dobson’s life, billing him as a “cross-dressing” eccentric. Miller’s research tells a slightly different story.

“I would say that’s a dubious claim at best,” he explains. “Some people really go for it and say ‘Maurice would never have worn a dress’. I’ve heard that from a few people who knew him in the 1970s. They said that he was very well-dressed, and that he would wear fairly flamboyant clothes for a man at the time, but he never would have put the dress on.”

There’s a lot about Dobson that’s anomalous in the wider context of queer histories. When we hear stories of same-sex desire between men before the decriminalisation of (most) homosexual acts in 1967, they’re usually tales of criminalisation. Dobson was never arrested, but that doesn’t mean that Barnsley in the 1950s and ‘60s was a haven of tolerance and acceptance.

Miller points to the Goodliffe case of 1954 as proof. In a nutshell, a man named John Wilson had drunken sex with an old friend, Peter Goodliffe. What started as a hook-up behind a pub turned violent, as Wilson punched, kicked and stabbed Goodlife before stealing his watch, money and trousers.

Goodlife reported Wilson, which resulted in a lengthy prison sentence. Yet Goodliffe’s account led him to be prosecuted too. In court, he detailed sex with numerous local men, from miners to office clerks, giving a testimony described by policemen as “so shocking [that] most of it could not be read out in court.”

Clearly, Dobson wasn’t the only man in Barnsley with same-sex partners before decriminalisation, but he kept his relationship with Halliday largely private. They were a known couple, and Miller says that their love was “certainly not unchallenged within the community,” but they weren’t having sex in public, cruising or sleeping with multiple partners, all of which were more likely to get you arrested.

By contrast, Miller says police officers seemed to quite like Dobson. He was tough, could handle himself in a fight, and was surprisingly politically conservative. Despite his mining history, he was even a “fan of Margaret Thatcher”.

Seemingly, locals just saw Dobson as a colourful eccentric, a man with a penchant for sharp suits and light make-up who taught his parrot to tell the local kids to “bugger off” when they lingered too long.

According to various testimonies, Dobson was a champion boxer in his army regiment, a collector of fine antiques and a renowned dancer. However, Miller said some participants in his oral history project contested these claims, advising him to take these stories with a pinch of salt.

“There’s probably a different Maurice for everyone that remembers him,” he explains. “I did some interviews with people who weren’t comfortable being recorded, so I did speak to a few people off-the-record who told me things that were different to the narratives we sometimes hear.”

These nuances and complexities make the story of Maurice Dobson so fascinating. Usually, queer histories are either rooted in criminalisation or the stories of the wealthy upper classes. They’re rarely set in working-class mining villages or feature men in seemingly harmonious, same-sex relationships.

Whether they loved or hated him, Darfield’s locals paint vivid pictures of a charismatic and unique man whose legacy is worthy of preservation.

About the author

Jake Hall is a freelance journalist and author living in Sheffield, England. Jake’s first book, ‘The Art of Drag‘, was an illustrated deep dive into the history of drag, published by NoBrow Press in 2020. Their latest book, ‘Shoulder to Shoulder‘, is a history of queer solidarity movements over the last 6 decades.

For years, Jake has been fascinated by everything from queer culture and histories to fashion, film and climate activism, and they’ve written for publications ranging from ‘Dazed Digital’ and ‘The Independent’ to ‘Refinery29’ and ‘Cosmopolitan’. They’re also a keen book fan and reviewer, publishing regular reviews on their Instagram.

Discover your historic local heritage

Hidden local histories are all around us. Find a place near you on the Local Heritage Hub.

Further reading