Span Developments was formally founded in 1957 by the architect Eric Lyons (1912-1980), the architect-developer Geoffrey Townsend (1911-2002) and the developer Leslie Bilsby. Their combination of expertise and enlightened property speculation was unusual at the time.

Both Bilsby and Townsend, with whom Lyons had been an architectural student at the Regent Street Polytechnic, were keen advocates of modern architecture and design.

Span’s aim was to build affordable up-to-date homes that fostered community and were fully integrated within landscaped gardens. Ivor Cunningham joined Lyons’ practice in 1955, designing both buildings and landscapes and in 1962 it was renamed the Eric Lyons Cunningham Partnership.

In the mid-1940s Lyons moved to Mill House in Surrey, which remained his family home and studio until his death there in 1980.

Span’s 73 developments created over 2,000 homes, ranging from a handful of houses to a new village, with the majority being small estates of between 15 and 50 units.

Span targeted the middle classes, offering relatively low-density homes on leafy suburban sites. Up until now, such speculative developments had largely been the preserve of the wealthy.

Lyons aimed to find alternatives to the repetitive semi-detached layouts and revivalist styles that characterised the inter-war suburbs; instead designing housing at higher densities within attractive shared grounds. In the words of Span literature, to “…span the gap between the suburban monotony of the typical ‘spec’ development and the architecturally-designed individually built residence that has become, for all but a few, financially unobtainable.”

Lyons and Townsend partnership

Eric Lyons had pedigree. In 1936-7 he worked for the architectural practice of Maxwell Fry (1899 to 1987) and his hero Walter Gropius (1833 to 1969), émigré from Nazi Germany, founder of the Bauhaus School in 1919 and pioneer of the Modern Movement.

The test of good housing is not whether it can be built easily, but whether it can be lived in easily.

Eric Lyons

Prior to the formal establishment of Span, Lyons and Townsend worked together in the late 1930s with Lyons designing speculative housing in west London, but their practice was interrupted by the Second World War.

After the War they reunited, working on small projects, including war damage work, with Lyons also designing a range of bentwood furniture.

Early work and the Span ethos

From 1946 Lyons and Townsend realised a range of small developments in Richmond and Twickenham. Their first large-scale scheme was Parkleys. It brought them to wide attention and pioneered what would develop as a prevalent architectural style from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s.

Span produced high quality, low rise housing using rationalised construction techniques at moderate cost. Flats were oriented for maximum sun and air. Interiors were open plan and bright.

Modern architecture was tempered with traditional finishes, such as tile-hanging or timber weather-boarding. Vehicles and pedestrians had separate access, with the latter taking priority. Garages were conveniently grouped together.

Parkleys also instigated covenants where residents belonged to a management company with responsibility for keeping the estate in good order, encouraging a sense of community.

Crucially, landscaping was integral to the design, then an innovative concept in speculative housing.

Span and landscape design

Eric Lyons believed strongly that…”The soft furnishings of nature should not be used to obscure spatial relationships but to enhance them…landscape should be the functional design of the space, not just a matter of bringing in a landscape-decorator to sprinkle some trees and cobbles around the place.”

The landscape design of Span schemes, was led for many years by Ivor Cunningham (1928 to 2007) and Preben Jakobsen (1934 to 2012). They incorporated existing mature trees and shrubs, along with informal planting, giving a naturalistic feel, peaceful communal areas and a sense of privacy for residents.

Span Developments, Blackheath

As the practice spread its wings with more schemes, developer Leslie Bilsby was focusing on the verdant Cator Estate in Blackheath, an area of 18th and early 19th century houses with extensive gardens, many of which had suffered war damage.

Against fierce local opposition from preservationists and initial planning refusal by Greenwich Council, Lyons and Span finally won planning permission, designing and building The Priory there: 61 flats and 49 garages.

Built in 1956, it was the first of 20 Span developments in the location. Most of Span’s developments were located in the older outer London suburbs, such as Richmond, Twickenham, Ham, Teddington and Blackheath where land values were cheaper.

Certain Span schemes engendered planning battles with Greenwich Council and the London County Council (LCC), the strategic planning authority, some going to public inquiry.

Yet Span’s early developments, including those in Twickenham, Putney, Wimbledon, as well as Blackheath (600 units there by 1964), made Lyons’ name and he received a number of awards from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government.

In an attempt to reform the planning system, Lyons in 1959 became a member of the Council of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), using it as a platform for his outspoken and uncompromising views. He became a renowned public figure and was President of RIBA from 1975 to 1977.

Span schemes beyond London

Eric Lyons and Span designed many developments outside London, with locations including East Sussex, Oxford, Cambridge, Cheltenham in Gloucestershire, Taplow in Berkshire and several in Weybridge, Surrey.

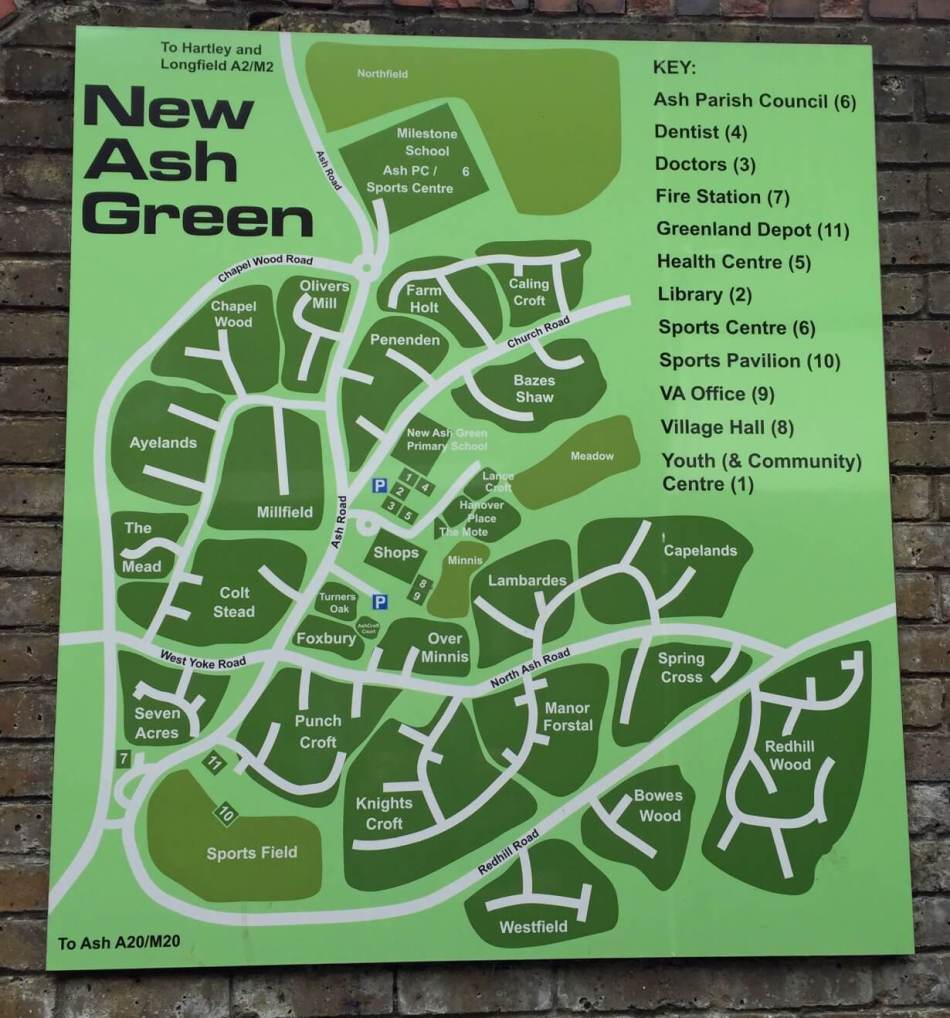

But Lyons’ and Span’s most ambitious and visionary project was to design a whole new community in the Kent countryside: New Ash Green.

New Ash Green, Kent

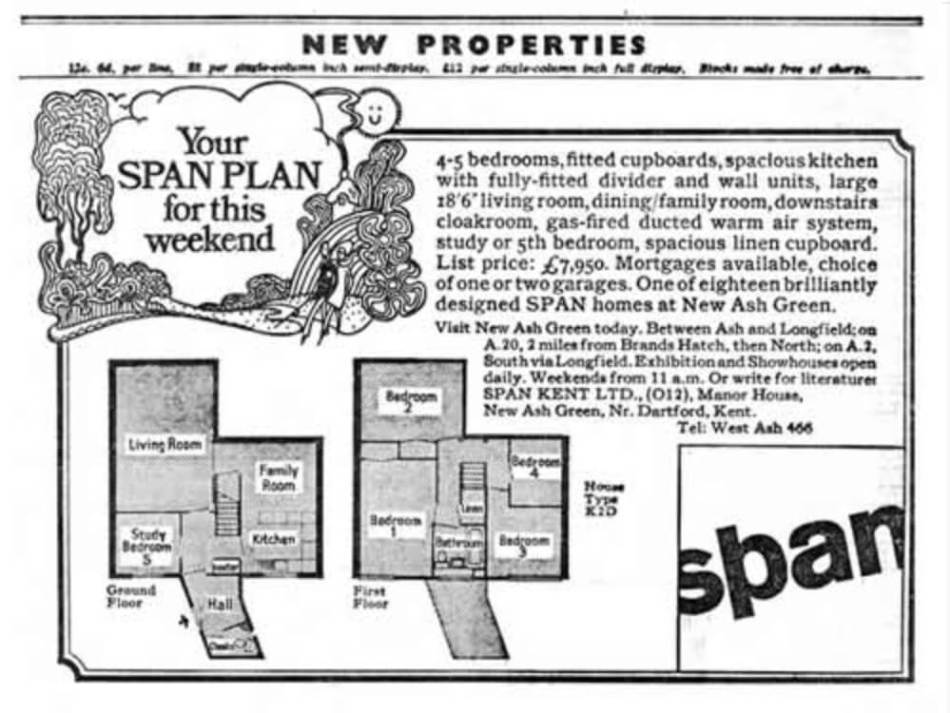

The masterplan was for a modern garden village for up to 6,000 residents from a wide spectrum of ages and backgrounds. In Span’s advertisements it was dubbed ‘social pioneering’.

Built on half of 160 hectares of former farmland, New Ash Green provided homes in a series of neighbourhoods of varied density. 2,000 of the homes, plus amenities, would be built between 1966 and 1971.

Homes would face or back onto common green space. Designs, as with previous Span developments, offered high quality landscaping incorporating retained mature trees, shrubs, and other features.

Residents were again required to be involved in the management of their neighbourhoods. Amenities included a shopping centre, clinic, primary school, pub, care home, library and church.

Planning permission was refused in January 1964 by Kent County Council, but the decision was later overturned. Construction began in 1966 and the first house was completed May 1967.

Many early residents of New Ash Green were under 30 with young families. They shared a pioneering spirit that wanted to embrace the new with a different kind of lifestyle. Sales boomed, peaking in 1968.

However, Britain’s severe economic downturn at the end of the 1960s led to a decline in sales of such homes. There was a squeeze on mortgages, with lenders having lost faith in modern designs, regarding them as unsafe investments.

With Span’s financial stability under threat, Lyons responded by designing homes that would appeal to the mortgage companies.

There would be limited house types; more standardised construction. But a negative report into Span’s ability to complete New Ash Green was a terminal blow. Ensuing restructuring saw a curtailment of Lyons’ design independence as consultant architect. He withdrew from the project December 1969, with Townsend and Bilsby also resigning. All work on the village halted.

The construction group Bovis took over in 1971 with other developers following, building further neighbourhoods but with less attention to design, green space and amenities. Lyons idealistic village masterplan was gradually diluted.

Span ceased to exist. It was a crushing blow to the partnership.

Eric Lyons and the public sector

Alongside the design of suburban estates, Lyons took on a significant amount of work for the public sector, including several London boroughs; work which later helped him keep afloat after the end of Span.

His public sector schemes, while exhibiting his characteristic rigorous detail and good design, are little known and are very different from Span’s work in the suburbs, in terms of scale and character. He found working as an architectural consultant for local authorities a trying business.

Among his several built schemes were Pitcairn House for the LCC, as well as 12 storey Castle House in 1965 with its ‘streets in the sky’ for the progressive Southampton housing authority.

But the largest public sector scheme he was involved with was at World’s End in London’s Chelsea.

Eric Lyons was appointed early in 1963 to produce an initial scheme. After public inquiries and planning issues, his third design was finally given permission in 1966. Whole streets of Victorian terraced houses were swept away by the development, with residents subject to Compulsory Purchase Orders.

The high-density estate was of pre-cast concrete construction, visually softened by brick cladding. Each flat had its own private balcony and amenities included a school, shops, church, community centre and underground parking.

Having never designed such a huge scheme before, Lyons formed a partnership with H T (Jim) Cadbury-Brown (1913 to 2009). They were joined by John Metcalfe and Span’s original landscape architect, Ivor Cunningham.

Cadbury-Brown, with his architect wife Elizabeth and Metcalfe, produced most of the estate’s working drawings from Lyons’ designs.

Construction started in 1969 but was beset by brick shortages and a protracted national building strike. The first residents did not move in until 1975.

World’s End was one of the last great extensive developments of the late 1960s/early 1970s and one of the most successful.

High rise estates eventually fell out of favour with the public after becoming associated with construction defects and social problems.

The later years

In 1976, the original Span partnership of Eric Lyons, Geoffrey Townsend and Leslie Bilsby was relaunched, reuniting with landscape architect Ivor Cunningham, and bringing in one of Lyons’ architect sons, Richard, as a partner.

Four years earlier, Lyons had won a competition to design a masterplan for a holiday village, Vilamoura, on the Algarve, Portugal.

Only the first phase was realised before Lyons’ death in 1980 (subsequent phases were completed by Cunningham and Richard Lyons).

A world away from his earlier restrained Modernism, Lyons’ designs for Vilamoura featured a vernacular style of pitched roofs, decorative tiling and brickwork. This more relaxed, vernacular idiom influenced his subsequent designs for Mallard Place, Twickenham, London (above), as well as his last public housing schemes, the Westbourne Estate in Islington, north London, and Fieldend in Telford, Shropshire.

Lyons was awarded a CBE in 1979. A year later, in his late 60s, he died from motor neurone disease.

Written by Nicky Hughes

Further reading