by Nate Holdren

In his post to open this Forum on political economy, Mikkel Flohr argues that Marxism can help us to treat “ideas as socially embedded, historically conditioned, and politically effective.” I agree completely with Flohr’s valuable contribution. In this post, I propose three adjacent senses of the term ‘political economy,’ intended to help us to operationalize ways of treating ideas in our concrete research as intellectual historians. I see this as a matter of working at a slightly different degree of analytical abstraction than Flohr, which I intend as complimentary to, rather than in competition with, the approach that he outlines. As I’ve argued elsewhere, an essential element of Marxist analysis is that it operates at multiple levels of abstraction, as Marx’s Capital itself demonstrates. By articulating multiple concepts of political economy in intellectual history, I hope to provide some language to help us transition between or speak across these different levels of analytical abstraction with greater clarity.

We can understand political economy as a name for the relationships of domination in capitalist society that serve as the background context influencing intellectual life; as a set of institutions in social life inhabited by distinct modes of thinking, such as law, medicine, or management science; and as a way for actors to navigate capitalist society while avoiding thinking about unjust aspects of this social world. This post places particular emphasis on this third understanding of political economy, which allows intellectual historians to think through what I term capitalism’s unthought: epistemically invisible phenomena and the intellectual resources that effect their invisibility, particularly when circumstances threaten to make those phenomena erupt into view. In Capital, Marx describes such social phenomena as occurring “behind the backs” of a given set of actors. Placing conscious emphasis on capitalism’s unthought has the virtue of encouraging intellectual historians to reckon with Marxism’s most distinguishing feature among political traditions, namely its particular understanding of and emphasis on social totality.

The three senses of political economy that I present here are a rational reconstruction that makes explicit the implicit approach to these matters that I relied on—not always consciously—in my own book, Injury Impoverished: Workplace Accidents, Capitalism, and Law in the Progressive Era. My book’s broader theoretical aim is to understand how people in positions of power conceptualize their power and think through how to wield it in social life. Its concrete object of analysis is the conceptualization of workplace injury by institutional authorities. To that end, I studied professional communications between legislators, lawyers, physicians, and social scientists who sought to inform policy making. This included looking at workaday texts those actors produced (such as letters, memos, and transcripts of their remarks in spoken discussions at professional gatherings) as well as the bodies of ‘theory’ that informed their discussions, i.e., medical and legal treatises (such as Ernst Freund’s 1904 The Police Power and Harry Mock’s 1919 Industrial Medicine and Surgery), social scientific investigations (like Crystal Eastman’s 1910 Work Accidents and the Law), writings by economic thinkers (like Alfred Marshall’s 1898 Principles of Economics), and so on. The more general point here is that institutional actors can be situated in the context of capitalist social relations in the sense, on the one hand, of being actors in specific institutional setting and, on the other hand, of inhabiting intellectual milieus that serve to make sense of life within, and to address specific problems of, capitalist societies. Marxist and Foucauldian approaches dovetail productively here, helping to draw out how “governance” is a form of domination with diverse concrete expressions across different institutional locations.

***

The first way in which intellectual historians can engage political economy is as a set of background conditions, social processes “of setting limits and exerting pressures” on thought. Like Marx’s own analysis of the relationship between social being and social consciousness, this means viewing ideas as shaped but not mechanically produced by events arising from the dynamic interplay of the dominant social forces. As E.P. Thompson once expressed with typical flair in his “Poverty of Theory”:

Experience walks in without knocking at the door, and announces deaths, crises of subsistence, trench warfare, unemployment, inflation, genocide. People starve: their survivors think in new ways about the market. People are imprisoned: in prison they meditate in new ways about the law. In the face of such general experiences old conceptual systems may crumble and new problematics insist upon their presence. (1981 edition, p. 9).

In this sense, political economy serves intellectual historians as a contextualizing device, attending to capitalist society’s means of generating life-changing and thus thought-prompting, experiences that intercede in our lives. The object of intellectual historians is, at least in part, to conceptualize those experiences in narrative form, meanwhile unearthing the discursive resources that underlie their creative changes over time. In my view, Marxism offers a particularly effective account of how and why capitalism generates such experiences. Of course, Marxists themselves disagree on a great deal, as demonstrated in Søren Mau’s Mute Compulsion, Tony Smith’s Beyond Liberal Egalitarianism, and Jack Copley’s Governing Financialization.

Second, intellectual historians can think about political economy as an institutional archipelago continually produced by thinking people. Each institution within the larger social division of labor has its own characteristic modes of thought. On a mundane level, corporate legal departments tend to think in terms of law, medical department in terms of medicine, company’s accountants in terms of dollars and cents, and so on. While specific institutions are distinct insofar as their personnel work (literally and figuratively) through institutionally specific problems according to given patterns and rules, personnel across institutions also interact with each other in complex ways that are sometimes conscious and sometimes unconscious for the institutional actors involved.

Political economy in this second sense directs intellectual historians to investigate structures of thought that are local to different institutions, whether public or private. In the method associated with this understanding of political economy, one must not only attend to each institution’s local specificities but also look beyond them in order to investigate how a given institution’s connections to other institutions and its place within the economy as a whole condition its thought. On the one hand, we may examine the expanding, downstream effects of decisions made in one original context. In the time and place my book studies (i.e., the Progressive Era United States), bosses created dangerous working conditions that led to lawsuits, legal decisions that led to lobbying by corporate management, new legislation that led to changes in business practices, and so on. On the other hand, we may analyze those interactions that tend to lead to ideas traveling beyond their immediate contexts. For instance, early twentieth-century legislators, medical experts, and corporate managers increasingly discussed companies’ costs for employee injuries in a language of risk management that originated with the insurance industry. I paid particular attention to how the language of “impairment” traveled from the insurance industry, where it operated as a technical term, into euphemistic usage by employers to sift acceptable from unacceptable employees. This inquiry is influenced by recent work on the history of insurance by scholars including Caley Horan, Dan Bouk, and Jon Levy. I was particularly inspired by Levy’s discussion of how the term “risk” evolved from a technical term in marine finance into a far more capacious category used in a wide range of ways.

A third way that intellectual history can think about political economy is as a form of thought that involves a kind of diminished theorizing or foreshortened self-reflexivity. I have in mind here uncritical theories—or perhaps “theories”—that are situationally reasonable, or situationally produced, but cannot account for the conditions under which those situations arise. Legal and economic thought, for instance, arguably takes capitalist society for granted, failing to situate themselves within the social totality. To return to my earlier example, the “local” theories of people in various institutional locations lack a larger theoretical account of those social relations in which they find themselves. For instance, as I attempted to show in Injury Impoverished, a lawyer does not need to understand the role of law in capitalism, and a corporate manager does not need to critically grasp their company’s role in reproducing capitalist social relations, and neither needs much awareness of the people harmed or ill-served by those institutions. Indeed, such awareness might well be an unwelcome distraction given their situational priorities and obligations. Political economy in this third sense has a dual meaning, being both a shorthand for these uncritical theories themselves, and an approach that investigates the conditions and processes that give rise to such thinking. Scholarship that thinks political economy in this way involves both showing the social world that goes unrepresented in these limited modes of thought, while also showing how these limits are not actually experienced or understood as limits for the actors involved. Simon Clarke provides an example along these lines in Marx, Marginalism and Modern Sociology, which analyzes how the marginalist revolution in economic thought set aside difficult but inconvenient questions in favor of more ideologically palatable ones.

For the purposes of intellectual history, we can think of this third sense of political economy as a matter of active avoidance or obfuscation of thought. The story of Thomas Crowder, an early twentieth-century physician who went deaf for unknown reasons, represents a case in point. The U.S. labor market for physicians at that time was not welcoming to a hearing-impaired person, so he was forced into a change of career, eventually becoming director of the medical department at the Pullman Corporation in Chicago. Pullman senior management ordered him to devise a plan to systematically discriminate against disabled people, screening them out as applicants and firing them from the company’s employment rolls. Crowder’s own life experiences meant he must have understood some of the resulting hardship for those screened out, and he alluded to this at conferences that he contributed to. There is little evidence that he tried to change senior management’s mind on this, and understandably so as there was a great deal of evidence to suggest they would not have been open to him doing so. At the same time, the hierarchical relationships in the business corporation and the bureaucratic manner in which companies processed information meant that the order-givers did not have to understand any of the ramifications of their decisions. They could treat the suffering of the disabled employees and applicants that they ordered Crowder to discriminate against as significantly out of sight and out of mind, along with Crowder’s own distress as he pushed people out of work in a way similar to how he himself had to leave the medical practice. The more general point I mean to make by this example is that the violence inextricably baked into class society tends to be, so to speak, actively unthought by some social actors in ways that only sustain capitalism’s systemic violence of the market.

Inquiry along these lines opens up possibilities for building on and radicalizing recent work under the neologism “agnotology,” which refers to the study of the social production of ignorance. Building on that work would involve intellectual historians focusing on how agnotology scholarship has examined how people in some institutional locations tend to have certain subjects systematically occluded from their consideration. This opens up possibilities for a partial shift in historiographical direction. Attention to political economy as capitalism’s (production of) unthought helps underscore that the study of the intellectual life of governance in capitalist societies is also the study of what the Marxist tradition often calls “barbarism” and theorist Werner Bonefeld, drawing on Theodore Adorno, calls “social coldness”: the forms of indifference to human well-being that proliferate in capitalism. Its empirical study would involve examining how relationships of subjugation and the violence they generate are justified, legitimated, or rendered natural by the subjects involved. This means that we can ask questions like: what intellectual resources do those in power rely on to insulate themselves from thinking about the world they benefit from, their own actions within it, and the inequalities systematically produced by that world? This “agnotological” understanding of political economy accords with philosopher Jacob Blumenfeld’s argument that being working-class involves not just material but also epistemic injustice, i.e. a systematic lack of recognition. Theorists like Bonefeld, Adorno, and Blumenfeld help draw out how this third sense of political economy folds into the first. Indeed, part of the contribution we can make as intellectual historians is demonstrating to less theoretically-inclined fellow historians that the work of such theorists can in fact be productively deployed in empirical research: our subfield can stand as a beneficial gateway between philosophers and other theorists, on the one hand, and our fellow historians in other subfields. Attention to how capitalism exerts pressures and sets limits does not require us to investigate what I’ve been calling capitalism’s unthought, but more deeply investigating that lack of thinking requires a sense of the structural pressures and limits placed on the very act of thinking.

This third sense of political economy particularly amplifies the second sense, in that specific institutional locations tend to have their own local resources for avoiding certain subjects. Two recent empirical studies can be read as examining the time, place, and institution-specific linkages between the material and epistemic aspects of oppressive social relations: the historian Lori Flores’s article on how injuries to migrant forestry workers are occluded by what she calls “amnesic landscapes” and the sociologist Irene Vega’s study of how ICE agents psychologically resolve the moral dilemmas posed by acts of violence. These two studies, especially if read in tandem, productively draw out that these social phenomena are subject to empirical investigation, rather than being exclusively the province of theorists. Part of the value of the three senses of political economy I’ve tried to lay out here is that they encourage us to take different studies like this together, identifying resonances between works that don’t directly address each other. That kind of thinking can help us to examine in fairly granular terms how capitalist social relations and attendant modes of thought are organized, practiced, reproduced, (mis)understood, and contested by various people in different times, places, and institutional locations.

This third sense of political economy points again to the importance of Marxism. As a social theory, Marxism can allow us to see what is generally constitutively absent for historical actors in capitalist society. It helps us to explain the social context of their actions in ways that historical actors themselves did not fully comprehend, as well as explaining both why their comprehension had such limits and how those limits were often, so to speak, as much a feature as a bug. Marxist scholarship also confronts some difficulties that this sense of political economy as “unthought” helps bring to the fore, namely Marxism’s orientation toward social totality—in basic terms, its holism.

In a recent essay, the historian Gabriel Winant writes, echoing Thompson, that Marxism “is a total social theory” that includes “the sciences of structure, which interrogate how one level of existence or form of human activity is causally dependent on another.” Winant contrasts this to competing positions with Marxism, among which “only the sciences of contingency are represent.” Daniel Rodgers’s Age of Fracture could be summarized as providing a detailed account of the rising prominence of what Winant calls “the sciences of contingency” and the decline of “the sciences of structure” and “total social theory” in U.S. universities since around 1970. Rodgers’s book, despite being deeply insightful and containing a mountain of evidence, does not specifically explain why the scholarly turn from structure to contingency occurred. At the risk of putting too fine a point on it, lack of adequate conceptualization of structural power relations has a politics to it. How that politics is reproduced regardless of (or, in ways that actively condition) the intentions of scholars is itself a problem to be critically examined by scholars working at the overlap of intellectual history and political economy.

***

To conclude, as intellectual historians pursue further work with and upon the concept of political economy, it remains crucial to ground our analyses in the social-historical mechanisms that make this concept possible at all. Here, I have discussed three senses of political economy. First, political economy can serve to name capitalism-specific modes of social structure, meaning the context in which historical actors live and are shaped. Second, it can be understood as a name for particular institutional locations within the social division of labor, each of which has its own locally specific ways of thinking yet operates in important and often unconscious ways as an ensemble. Third, it can name a kind of active lack—what I’ve called capitalism’s unthought—that is itself structurally conditioned: in the active doing of our roles in specific locations in capitalist society we tend to have in mind concerns specific to time, place, and social location, rather than critical about the capital-dominated social totality. In other words, we cannot forget to think about the unthought. Investigating how that unthought is produced and how it facilitates capitalist production is a fruitful avenue for further inquiry in intellectual history.

This think piece is part of a JHI Blog forum: “The Return of Political Economy in Intellectual History.”

Nate Holdren holds a Ph.D. in history from the University of Minnesota and is an Associate Professor in the Department of Law, Politics, and Society at Drake University. His book Injury Impoverished: Workplace Accidents, Capitalism, and Law in the Progressive Era received the honorable mention for the Organization of American Historians Merle Curti Intellectual History Award.

Edited by Jacob Saliba and Zac Endter.

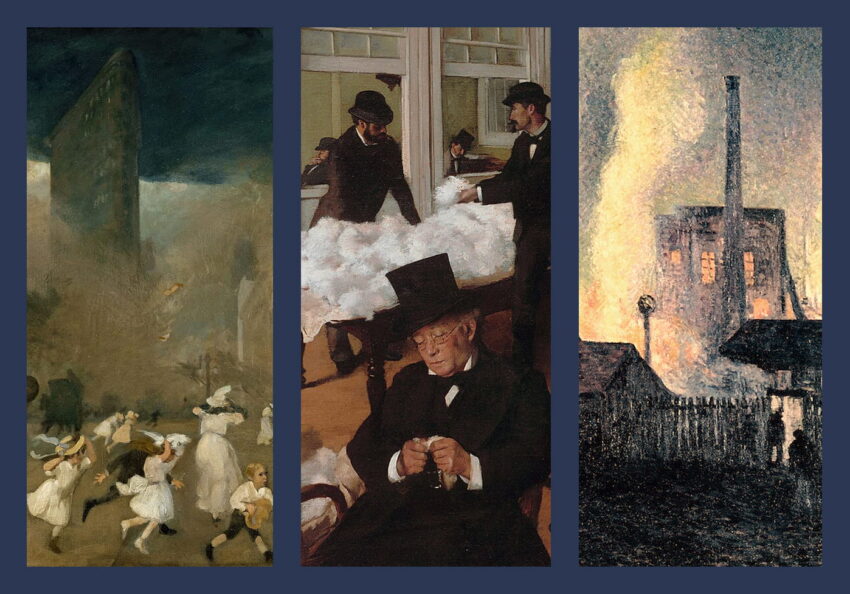

Featured image (from left to right): “John Sloan – Dust Storm, Fifth Avenue, 1906,” via Wikimedia Commons; Edgar Degas, “A Cotton Office in New Orleans, 1873,” via Wikimedia Commons; Maximilien Luce, “Blast Furnaces in Charleroi, 1896,” via Wikimedia Commons.