by Véronique Mickisch

For most, Marxist political economy is synonymous with planning. Perhaps no planning experiment has been associated as closely with Marxist economics as the First Five-Year Plan, initiated in 1928. This can be explained, at least in part, by the immense material changes it brought about within the Soviet Union. According to Robert C. Allen, the urban population doubled between 1928 and 1940, and literacy rates more than doubled within a generation, reaching 81 percent in 1939 (92). Gross industrial output rose sevenfold between 1928 and 1940. But the human cost of these changes was immense. A disastrous combination of forced collectivization, industrialization, and grain shortages led to low living standards for urban workers and a devastating famine in the major grain-producing regions. Historians Robert W. Davies and Stephen G. Wheatcroft put the number of dead from the Soviet famine in 1931–1933 at 7 million, a conservative estimate. Over half of these deaths occurred in Soviet Ukraine; 71 percent of them were of peasants.

It is not least of all because of these immense contradictions that Leon Trotsky’s analysis in The Revolution Betrayed (1936) long held significant influence on major scholars of this period, such as Moshe Lewin. Yet, since the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, it has become anathema for most Soviet historians to disassociate Stalinism from socialism and Marxism. Instead, it has become commonplace to speak of the First Five-Year Plan as a “second revolution” or, more pointedly, the “Stalinist revolution,” be it as celebration or critique. Ironically, we have now circled back to the arguments of the 1930s, when both the Stalinist regime and The New York Times described the First Five-Year Plan as a manifestation of “Marxism in practice.” But then as now, such arguments obscure one fundamental aspect of the reality of the First Five-Year Plan: that the far-reaching socio-economic transformations of that period were accompanied by the escalating suppression of classical texts of Marxist economics and, specifically, the increasingly violent repression of Marxist economic thinkers, who criticized the conception of building “socialism in one country” from the standpoint of the world-wide division of labor. The “Marxism” of “Marxism in practice,” thus, deserves critical reappraisal.

***

In the years immediately following the formation of the Soviet Union in December 1922, the conflict between an internationalist minority around Leon Trotsky—the Left Opposition—and a faction around Joseph Stalin—largely associated with the program of building “socialism in one country”—dominated Soviet political and intellectual life. After the expulsion of the Left Opposition from the Soviet Communist Party in December 1927, the wave of repression that first targeted Trotskyists quickly evolved into a cascading tsunami of press campaigns and purges. Over a decade later, the regime had eliminated almost all representatives of heterodox Marxist political economy and theory from public debate and institutions.

In 1928–1929, virtually all Left Opposition economists were arrested and exiled. Many of these scholars had been trained at the elite Institute of Red Professors in Moscow. By 1931, most of them were imprisoned in the Verkhne-Uralsk politisolator or “political isolator” (just north of what is today Kazakhstan). In 1931, one of these prisoners, Elizar Solntsev, co-authored a lengthy document that focused their critique of the First Five-Year Plan on “the struggle against the theory of socialism in one country” because it “. . . determines the general approach to economic policy, it determines the line of the leadership in the class struggle both within the USSR and outside of it” (32). Under conditions of the global division of labor, they wrote—echoing Trotsky’s earlier critique of “socialism in one country”—autarkic planning was not only unviable but also dangerous, for “the economy of the USSR is developing under the pressure of the world economy” (25). Their scathing Marxist critique of the policies of forced collectivization and industrialization pointed to the vast economic imbalances these policies created and the danger of a civil war in the countryside.

Remarkably, it was only in 2018 that Russian researchers discovered these writings hidden within the walls of Verkhne-Uralsk. This long-lost critique of the First Five-Year Plan by imprisoned Soviet Marxist economists, thus, radically shifts our understanding of the place of Marxist political economy in intellectual history—rather than embodying the paradigmatic realization of Marxist economics, the First Five-Year Plan was in fact bound up with the removal of an entire body of Marxist economic thought from the canon.

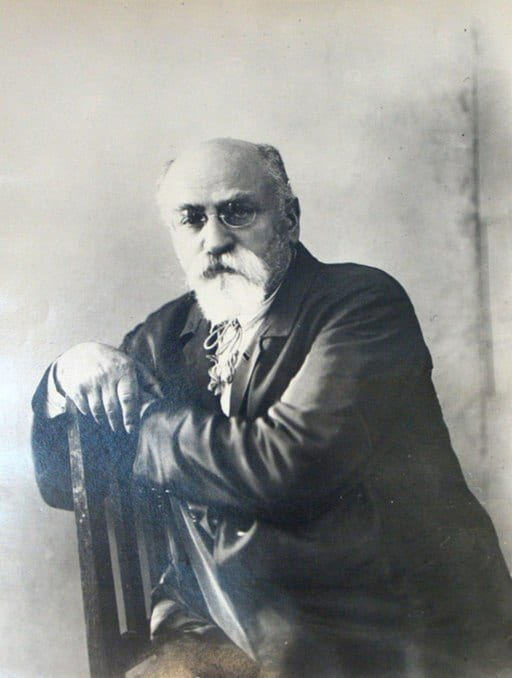

The fate of the Institute of Marx and Engels (IME) best illustrates how the mounting wave of terror swept away ever-larger sections of the institutional framework and personnel for the study of Marxism that had emerged after the 1917 Revolution. In the 1920s, the Institute was the principal institution in the world for the theoretical study and publication of the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, including some of their major writings on Marxist philosophy and political economy. From its 1919 founding until its closure in 1931, the IME was led by the veteran revolutionary David Riazanov. This work involved extensive collaboration with the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt (ISR), which, until 1931, was headed by Riazanov’s long-time friend, the Austrian Marxist Carl Grünberg. Via the ISR and the German Communist Party, several German communists went to Moscow to work for the IME. Two of them, Karl Schmückle and his wife, Anne Bernfeld-Schmückle, played a particularly important role in deciphering many of Marx’s early writings.

Riazanov’s closest collaborators were often political dissidents. Isaak Rubin, a long-standing member of the Jewish Labor Bund, headed the cabinet of political economy. His deputy, Evsei Kaganovich, was a member of the Left Opposition until 1929. Vagarshak Ter-Vaganian, a leader of the Left Opposition until 1929, headed the cabinet for the study of Slavic countries. Polina Vinogradskaia, a young theoretician of the Opposition and the wife of the leading economist Evgeny Preobrazhensky, was also employed by Riazanov and centrally involved in the preparation of volumes 22 (1929) and 23 (1930) of the collected works of Marx and Engels. Elizar Solntsev worked for the Anglo-American cabinet of the IME and searched for various writings and correspondence of Marx and Engels for Riazanov during his stay in the United States in 1927–1928.[1]

During the First Five-Year Plan, the IME was transformed, in the words of Russian historian Mansur Mukhamedzhanov, from one of the USSR’s last bastions of “freedom of thought” to an “institute of censorship” (7–8). The campaign began with attacks on Isaak Rubin. Once the pre-eminent figure in Soviet political economy in the 1920s and an expert on Marx’s theory of value, Rubin was now denounced for “idealist mistakes” by trained Party economists who had put their pen in the service of the Stalinized Politburo. He was arrested, tortured, and put on the defendants’ bench of the “Menshevik Trial” of 1931.

The Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) used Rubin’s testimony under duress to go after Riazanov and the rest of his staff. On February 13–14, 1931, at the height of the First Five-Year Plan, the OGPU raided the IME. They arrested Riazanov. 130 out of the Institute’s 244 employees were fired. Among them was every single employee who had ever supported or maintained personal ties to the Left Opposition, as well as many former Mensheviks and Bundists. With one exception, it also included all former members of the Institute for Social Research (ISR) from Frankfurt. The purge, thus, marked the conclusive end of the previously significant ties of the IME with the ISR, severing one of the most important avenues for the international exchange of ideas involving Soviet Marxist theorists.

Later that year, a letter by Stalin to the editors of the journal Proletarskaia revoliutsiia [Proletarian Revolution] provided the basis for an even more intense campaign of suppression. “Some Questions Concerning the History of Bolshevism” (1931) specifically disavowed all German Marxist theoreticians, notably Karl Kautsky and Rosa Luxemburg, denouncing them as “semi-Menshevik,” and claiming that Lenin had been required to wage an implacable struggle against them. Some eight years earlier, in December 1924, Stalin had declared that the Soviet Union could build “socialism in one country.” Now, he had developed and begun to enforce a theory of “Marxism in one country.”

***

This repression had far-reaching consequences for Soviet economic thought. Economists who evoked the writings of Rosa Luxemburg and Rudolf Hilferding, both classics of Marxist economic theory, were suddenly denounced as “Mensheviks” and accused of “Trotskyist errors.” The writings of Luxemburg were especially associated with the theory of permanent revolution espoused by Stalin’s nemesis, Leon Trotsky—not without reason.

By the end of the First Five-Year Plan in 1932, Party economists who were still at large were forced to avoid any mention of certain Marxist economic thinkers, lest they risk persecution. In their writings, they increasingly had to limit themselves to narrowly prescribed quotes from Lenin and the now omnipresent Stalin. The bearers of actual expertise in the social and natural sciences and in Marxism were now a direct target of repression and, eventually, an extraordinary campaign of mass murder.

As historians Yehoshua Yakhot and Sheila Fitzpatrick have observed, the experts’ replacements were, more often than not, young and ambitious novices. Their positions within the Party and state apparatus depended less on ability and erudition but rather upon their willingness to produce writings according to the requirements of the rigidly controlled and rapidly shifting Party doctrine. Riazanov foresaw the broader implications of this process as he himself was under attack. In a letter from 2 February 1931, written less than two weeks before his arrest, Riazanov presciently warned of the implications of the elevation of Stalinist “court philosophers” (in the words of Yakhot) to the highest levels of intellectual life. “It is ridiculous, absurd, and stupid, to demand that an expert philosopher develop, say, a theory and methodology of planning. . . . As if for all this it were enough to put a philosophical cap on one’s head and look in the appropriate paragraph of Hegel’s big or small logic [in his Encyclopedia, VM]!” This “philosophical epidemic,” Riazanov raged, meant that people who knew “everything ‘in general’ and nothing concretely” were now calling the shots in all academic fields.[2] After his arrest, Riazanov, who had been celebrated on the occasion of his 60th birthday in 1930, was never to publish or walk free in the USSR again.

The new IME leadership worked together with the People’s Commissariat of Interior Affairs (the NKVD, successor to the OGPU) in vetting, censoring, and purging its staff. From at least 1935, it also began to destroy documents and pulp books from the IME’s vast library.[3] These actions were part of a much broader effort to eliminate from circulation the books, articles, and pamphlets produced in the 1920s, especially by figures associated with the Left Opposition. For instance, a textbook compiled by Elizar Solntsev on “The World Economy After the War” was published in 1926 to 10,000 copies. As late as 1973, the Interior Ministry listed this book as one “that had to be excluded from libraries and the bookstore network.” Half a century later, the book remains a bibliographic rarity.

Except for Polina Vinogradskaia, who was arrested but not killed, every one of Riazanov’s collaborators at the IME mentioned here was dead by 1938. Riazanov himself, who had dedicated some 50 years of his life to the socialist movement, was executed in January 1938.

***

The fate of the IME underscores that what we commonly understand as the Marxist tradition of political economy has been critically shaped by the absence of a vast portion of that tradition. The bearers of that tradition and their writings were buried in the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. I argue that any serious discussion of Marxist economic thought in the twentieth century must involve a systematic effort to recover this legacy. Fortunately, the growing digitization of archival and library holdings facilitates this work, even under conditions where the current war in Ukraine has made physical access to Russian archives much harder.

Quantitative methods and data sets are a powerful tool to identify the biographies and the works produced by those who were murdered. For instance, a quantitative analysis I compiled of the fate of the graduates of the elite Institute of Red Professors from 1924 to 1928 indicates that over 58 percent of them were either executed or arrested. Over 70 percent of the graduates who were, at one point or another, associated with the anti-Stalinist Opposition—at least a fifth in every one of these respective cohorts—were murdered. For the graduates who continued to be associated with the Trotskyist Opposition in the 1930s, such as the above-mentioned Elizar Solntsev and Fedor Dingelshtedt, the murder rate rose to 100 percent. Their perspective on Soviet economics was not refuted, in either theory or practice. Instead, it was silenced. Thus, to speak of Soviet planning and Soviet-Marxist economics without considering their legacy unavoidably perpetuates the destructive legacy of Stalinism.

Overcoming this legacy poses definite methodological challenges. A history of political economy in the USSR cannot be written as either an economic history that abstracts from politics and ideology or as an intellectual history that remains aloof from political and socio-economic history. The violent selection of traditions of economic and political thought that occurred in the Soviet Union was inseparably tied to the political struggle that convulsed the Soviet Party and the Communist International in the 1920s and 1930s.

Therefore, historians of the Soviet Union and political economy must “re-turn” to a study of the political history of the communist movement. Likewise, economic historians must examine the different traditions of economic thought that asserted themselves in the political decisions taken and not taken by the Soviet leadership. A rigorous study of the vast number of published or unpublished primary sources, which are now increasingly available, is an indispensable precondition for this work. For all those ready to engage in this task, the history of political economy and Marxism in the Soviet Union contains an almost overwhelming number of riches, waiting to be discovered, studied, translated, and discussed.

This think piece is part of the forum “The Return of Political Economy in Intellectual History.”

[1] Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv sotsial’no-politicheskoi istorii (RGASPI), f. 71, op. 50, d. 333.

[2] Riazanov to Yaroslavsky, February 2, 1931, RGASPI, f. 374, op. 1, d. 21, l. 46.

[3] RGASPI, f. 71, op. 3, d. 91.

Véronique Mickisch is a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences (TIAS) at Tsinghua University in Beijing. She received her PhD in History from New York University in 2025 for her dissertation “Party Economists, the Left Opposition, and the Rise of Stalinist Economics, 1917–1938.” Her publications include the article, “Jewish Historiography between Socialism and Nationalism: A Portrait of Historian Isaiah Trunk” and an interview with Alexander Dmitriev on Lukács and the early history of the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research.

Edited by Disha Karnad Jani

Featured image: Photo of David Riazanov (1923), public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.