Giles Gilbert Scott (1880-1960) was a scion of an eminent Victorian architectural dynasty.

His grandfather was George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who built masterpieces such as London’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall, the Albert Memorial, and the Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras Station.

His father, also George Gilbert Scott (1839-1897), leading designer of workhouses, created significant buildings that included the London churches of All Hallows, Southwark and St Agnes, Kennington.

Following family tradition, Giles Gilbert Scott himself designed many Anglican and Catholic religious buildings nationwide, as well as a number of war memorials. He also created some of the country’s most important and, revered secular buildings and structures.

Here we look at 5 of his key works…

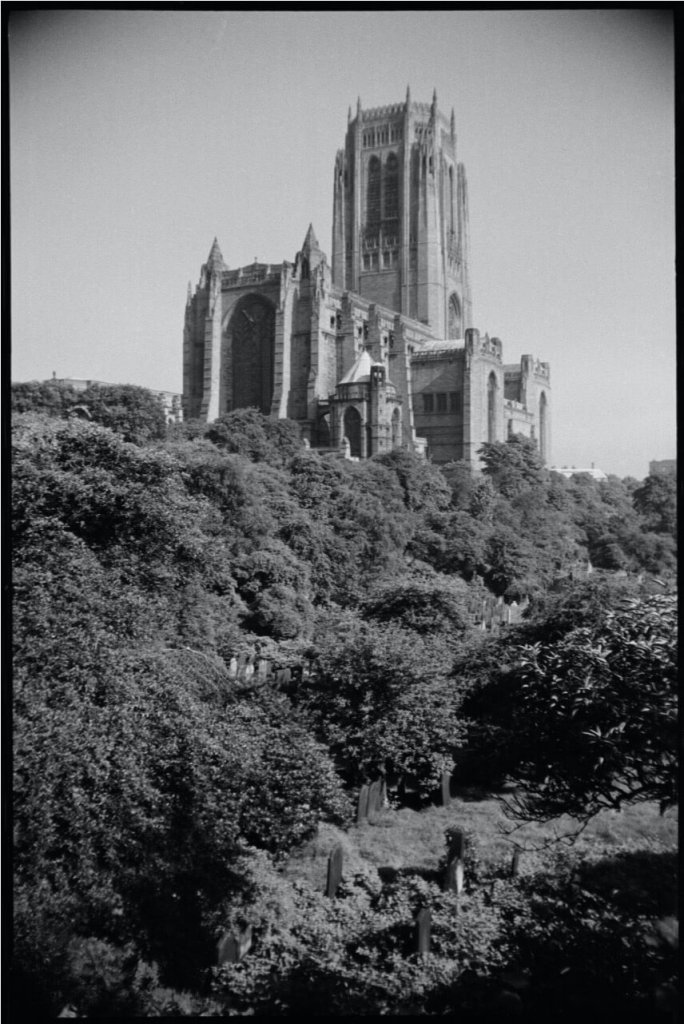

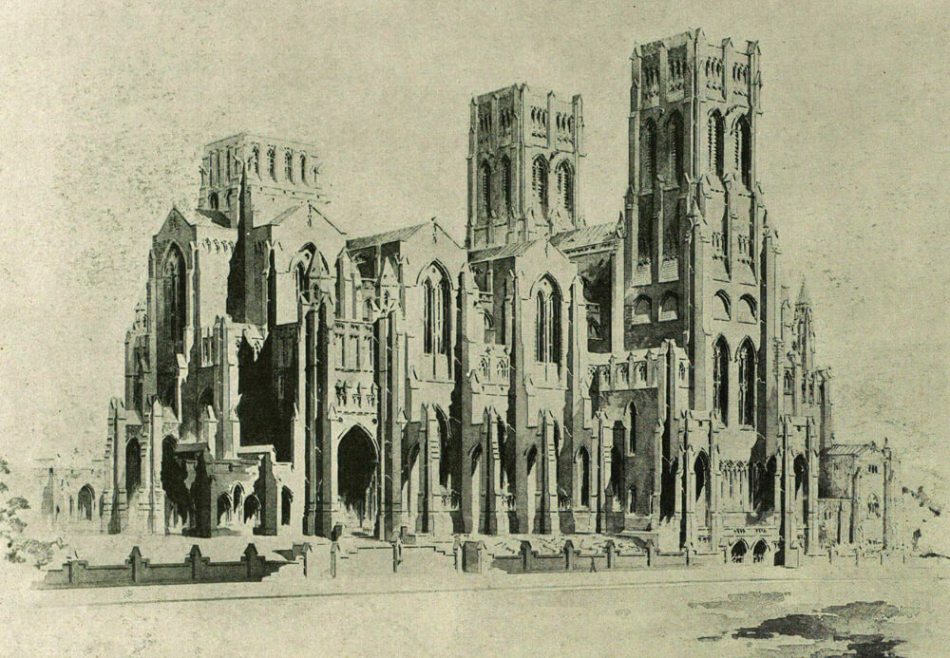

Anglican Cathedral Church of Christ, Liverpool

Foundation stone laid 1904, completed 1978

In 1901, the Diocese of Liverpool announced a competition to design an Anglican cathedral in Liverpool, only the third cathedral to be built in England since the Reformation of the 16th century (following St Paul’s and Truro cathedrals). There were 103 competition entries.

The judges included architects George Frederick Bodley (1827-1907) and Richard Norman Shaw (1831-1912).

The committee were astonished to discover, on opening the nom-de-plume envelopes in 1903, that their choice of architect with his Gothic-Revival design was Giles Gilbert Scott, only 22 years old and a Roman Catholic.

The choice was immediately controversial due to his youth, religious persuasion and lack of experience (he reputedly quipped that he had only ever designed a pipe-rack before). However, a compromise was reached whereby Bodley, who had been apprenticed to Scott’s grandfather and was in his 60s, was appointed as joint architect.

The partnership was not a happy one and Scott contemplated resigning. After Bodley died in 1907, Scott was appointed sole architect. The cathedral became his life’s work.

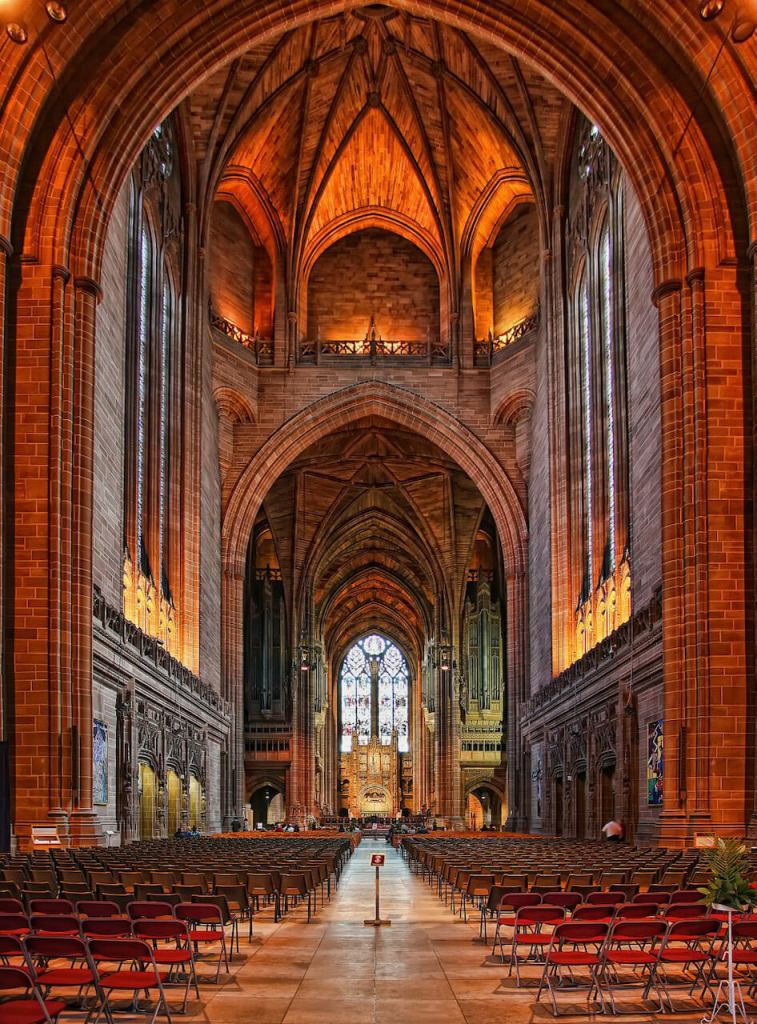

Scott promptly revised aspects of his winning design, feeling that it was too conventionally Gothic Revival. He persuaded the Diocese to let him start again with a simpler and more monumental design, with a single massive tower over pairs of transepts and a longer nave.

He drew on the Gothic style, with its pointed arches, ribbed vaulting and mouldings, but tempered it with the restraint and symmetry of Classical architecture.

The construction of the cathedral was severely limited during the First and Second World Wars due to shortages of manpower, materials and finance.

In 1924 the cathedral was consecrated in the presence of King George V and Queen Mary, and Scott was rewarded with a knighthood.

Scott continued to oversee and refine every aspect of the design. After Scott’s death in 1960, the west end was overseen by his former assistant, Roger Pinckney, and Scott’s former partner, Frederick G Thomas. Liverpool Anglican Cathedral was eventually completed in 1978. It is Scott’s architectural masterpiece and made his name, securing him many commissions.

Red telephone box

From 1912, the General Post Office (GPO) controlled virtually all of the national telephone network. In 1921, they developed the K1, the first national telephone kiosk. It was made of pre-cast concrete, painted cream with a red door. It was widely criticised.

Three years later, the Royal Fine Art Commission ran a limited competition for architects to design a new public telephone kiosk for the GPO.

The competition was won by Giles Gilbert Scott. His design, which went into production as the K2 model was in the classical style with a domed top and made from cast-iron with teak doors. Reflecting contemporary interest in Regency architecture, it has been compared to the work of architect John Soane (1753 to 1837). There is unproven speculation that Scott based the design on the mausoleum that Soane had designed for his wife Eliza in Old St Pancras churchyard. Scott was a long-term trustee of the Sir John Soane Museum in London.

Scott’s original colour for the K2 was silver with a blue-green interior, but the GPO changed this to red on grounds of cost. The K2 has been hailed as one of the most successful examples of British industrial design. Between 1926 and 1935, 1,700 were installed, mostly in London. Scott was commissioned to design other variants that could be installed nationwide.

The most common red telephone kiosk today is Scott’s K6, introduced in 1935 to celebrate the Silver Jubilee of King George V. It is smaller, with a horizontal glazing scheme instead of the vertical panes of the K2. By 1960, there were 64,000 of which 11,700 survive and 2,000 are listed.

Few of Scott’s telephone kiosks are in working order today, but some have been ingeniously repurposed, including as a library, mini art gallery, micro night club, ice-cream parlour, coffee shop, pub, bakery and defibrillator booth.

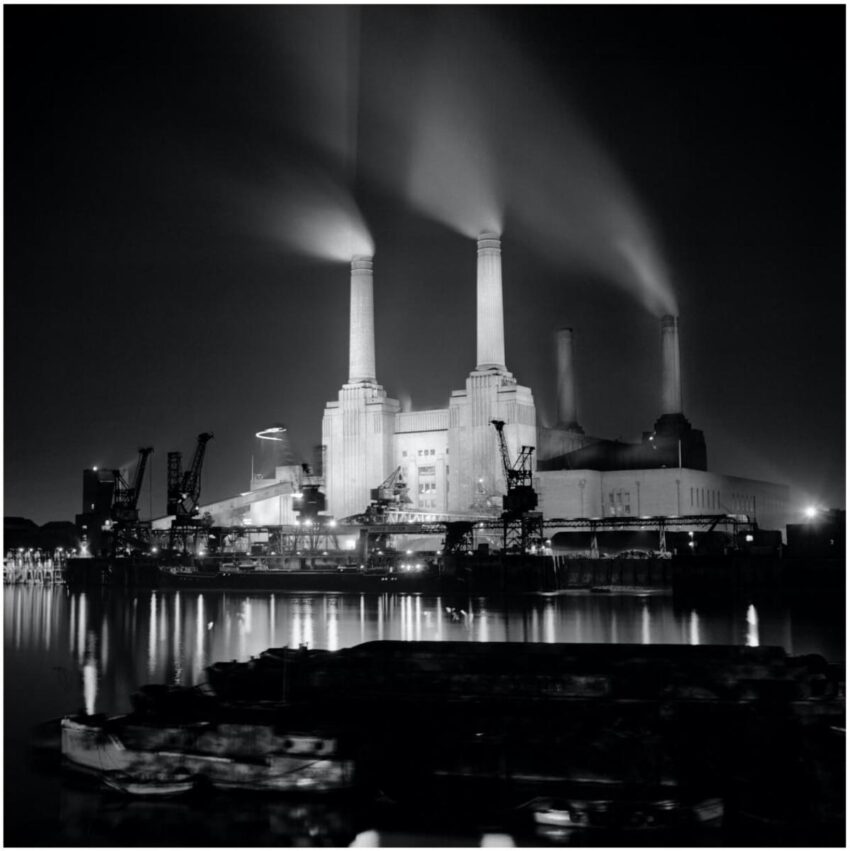

Battersea Power Station, London

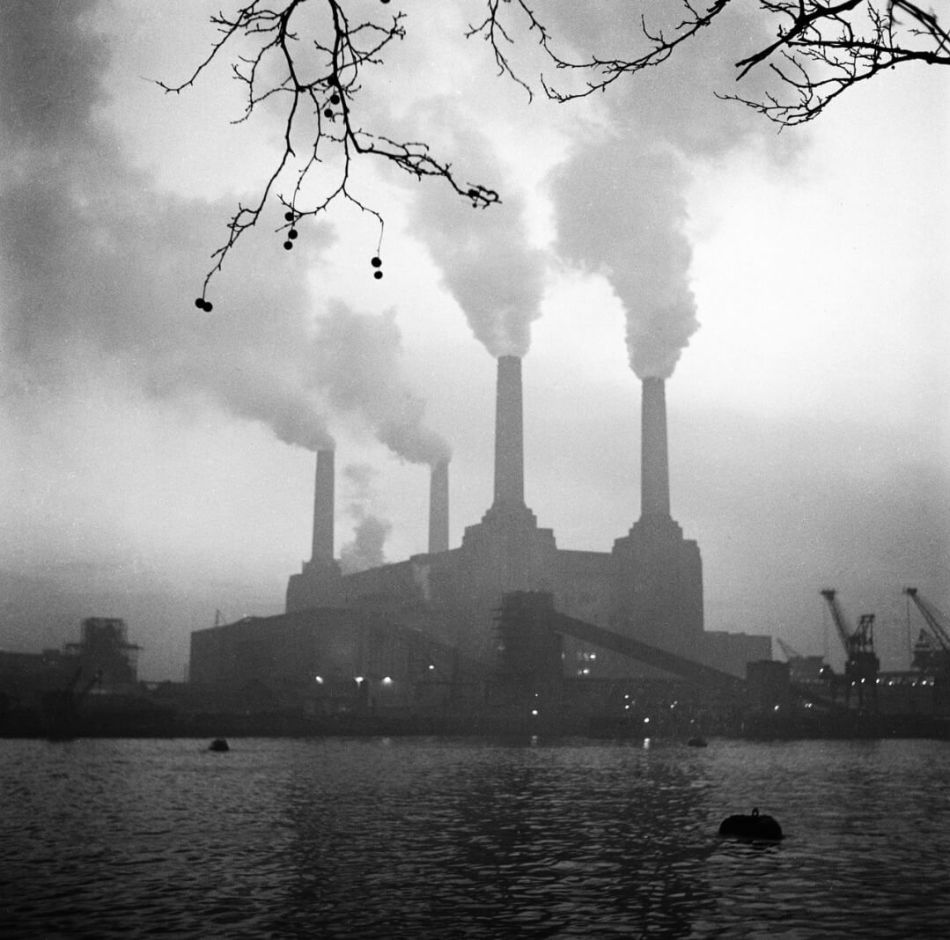

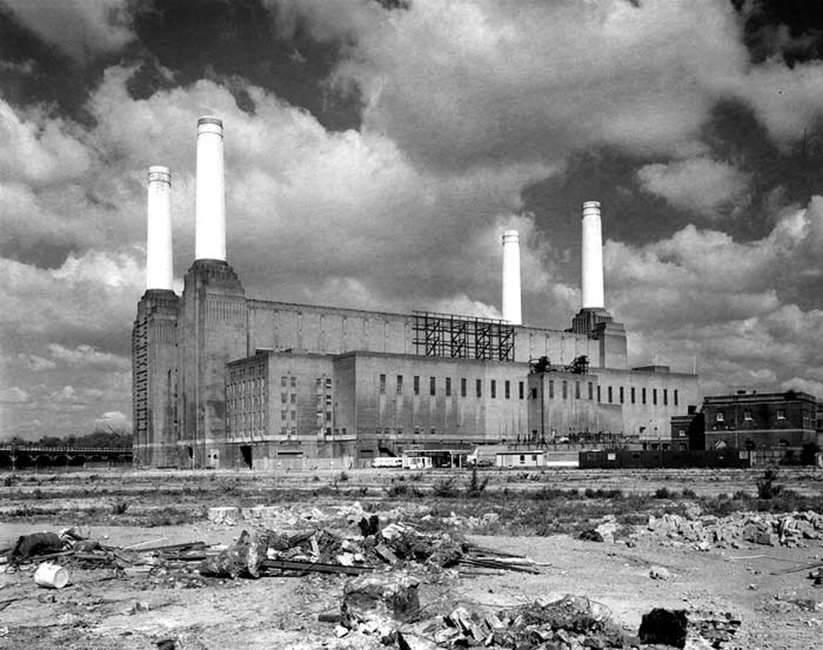

Construction began 1929, completed 1955

The London Power Company’s original proposal for a large coal-burning power station on the South Bank of the Thames met with strong opposition from local residents.

A design, by J Theo Halliday of the Manchester architectural practice Halliday and Agate, had already been adopted. To allay fears, Giles Gilbert Scott, now renowned for Liverpool Cathedral, was appointed as a consult architect to remodel the exterior.

In Scott’s hands, the structure became a brick ‘cathedral’ of power, with its colossal chimneys resembling fluted Doric columns. Expanses of sheer brickwork are contrasted with high-level bands of modernistic decoration.

It is one of the largest brick buildings in the world, a monumental example of an inter-war utilities building; evidence that an industrial structure can have aesthetic value and be integrated within an urban setting.

At its peak in the 1950s Battersea Power Station burned 10,000 tonnes of coal a week, producing one fifth of London’s electricity.

Station A was decommissioned in 1975 and Station B in 1983.

After decades standing empty, Battersea Power Station was completely renovated from 2013. Its famous chimneys were rebuilt in replica, with one of them functioning as a passenger lift.

It is now surrounded by blocks of flats with the colossal building redeveloped into a shopping mall, restaurants, offices, event spaces and penthouse apartments.

Waterloo Bridge, London

Constructed between 1937 and 1945

The original Waterloo Bridge was built between 1811 and 1817. It was named in commemoration of the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo.

In the early 20th century, one of the bridge piers settled in the river bed causing a dip in the bridge and making it structurally unsound. Although a temporary steel framework was built to support it, the London County Council (LCC) proposed the construction of a new bridge.

The old bridge was demolished. Giles Gilbert Scott was commissioned to design a replacement, along with the engineering firm Rendel, Palmer and Tritton.

Scott’s design combined elegant simplicity and restraint with engineering efficiency and functionality. The 5 span bridge used reinforced concrete, clad in Portland stone.

Construction of the new bridge began in 1937, but during the Second World War the workforce of 500 was reduced to 50. Heavy bombing during the Blitz (1940 to 1941) caused further disruption.

The bridge became known as the ‘Ladies Bridge’ as women were recruited as replacement workers. Research by historian Dr Christine Wall, along with oral history and photographic evidence showing a female welder at work on the bridge, has verified the story.

Waterloo Bridge was opened December 1945 by the then Deputy Prime Minister, Herbert Morrison, who as leader of the LCC had approved its construction.

Bankside Power Station, now Tate Modern

Constructed between 1947 and 1963

A power station had occupied the Bankside site since 1891, operated by the City of London Electric Lighting Company. Over the years it was criticised for being inefficient, noisy and polluting, discharging smoke and grit over the city centre.

A post-war proposal for a replacement power station met with opposition from all quarters, including objections that such a huge building would visually dwarf St Paul’s Cathedral opposite across the River Thames. Following a public enquiry, the government’s hand was forced by the brutally cold winter of 1947 coupled with a fuel crisis caused by a coal shortage. Demand outstripped supply and there were power cuts.

As a result, the proposal for a new power station was accepted, although modified to be oil-fired instead of coal-fired. Giles Gilbert Scott, was commissioned to design the complex.

Elegant and symmetrical, Scott’s second power station was set back from the Thames and built in 2 stages, in 1947 to 1952 and 1958 to 1963. It was steel-framed and roofed in reinforced concrete, with the exterior clad in over 4 million bricks.

The original intention was to have a tall chimney at either end. Instead, Scott designed a single slender central tower. This ‘campanile’ boiler flue, at 99 metres, was a little lower than the dome of St Paul’s.

By the late 1970s, the power station had become uneconomic and unacceptably polluting. It closed in 1981 and there were several development proposals. Applications to list the building were turned down and in 1993 it was issued with a ‘certificate of immunity from listing’.

In 1995 to 2000 the former power station was repurposed by the Tate Gallery to become a museum of modern and contemporary art, the Tate Modern. The conversion was designed by Herzog and de Meuron, who cleared the vast turbine hall as a space for temporary installations.

Giles Gilbert Scott was one of the most accomplished and sophisticated architects of his generation, respected for his ability to give the Gothic and Classical traditions a restrained yet monumental contemporary expression. As a designer he was admired for his masterly handling of natural light and the dramatic massing of his compositions.

At heart a church architect, Scott carried out many important secular commissions, including the Memorial Court for Clare College, Cambridge (1922 to 1932), Cambridge University Library (1930 to 1934), the New Bodleian Library at Oxford University (1935 to 1946) and the reconstruction of the chamber of the House of Commons (around 1944 to 1950).

On his death in 1960, Scott was described by Sir Hubert Worthington as “a singularly beautiful character, free of the jealousies that so often spoil the successful artist. He bore life’s triumphs and life’s trials with an unruffled serenity”.

Written by Nicky Hughes