Lined with vibrant restaurants and bustling shops, Chinatowns are lively culinary hubs at the heart of England’s cities.

A melting pot of diverse Asian cultures and communities, they are often marked by a distinctive Chinese archway, or paifang, which stands as a cultural symbol of Chinese heritage in England.

From the hidden stories of Chinese sailors to creating new culinary hotspots, England’s Chinatowns trace the development of Chinese communities in this country.

The Chinatowns in Liverpool, London, Manchester, Newcastle and Birmingham are emblems of local Chinese culture.

Discover how they have shaped the multicultural landscapes across England’s cities.

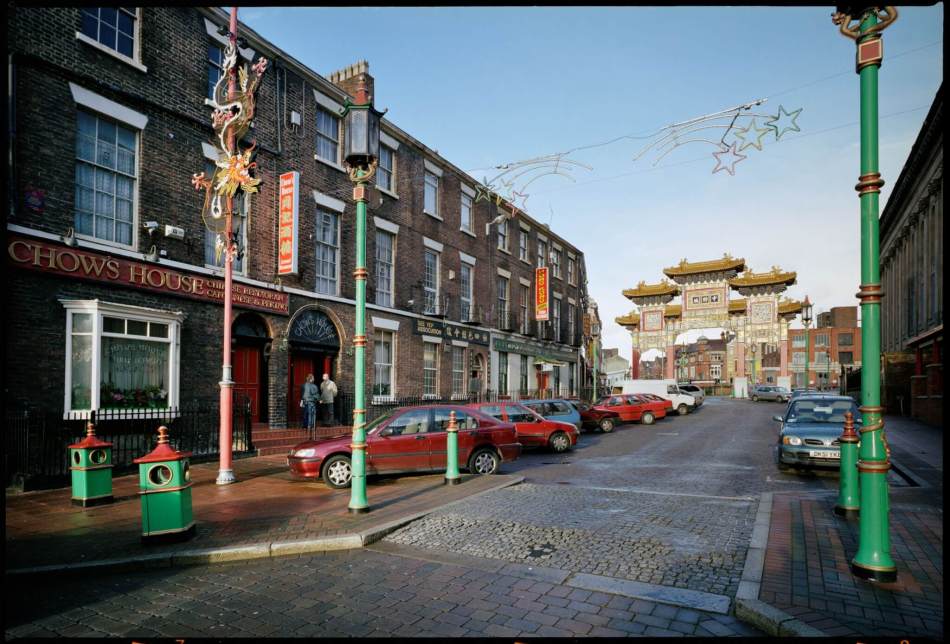

Nelson Street, Liverpool, Merseyside

Home to the oldest Chinese community in Europe, Liverpool has seen a long history of Chinese immigration in England.

In the 1860s, strong trade links were established between Shanghai, Hong Kong and Liverpool, importing silk, cotton and tea.

These shipping lines brought many Chinese seamen employed by British shipping companies to Liverpool, with Alfred Holt and Company opening boarding houses near the docks to accommodate their workers.

While the workers initially stayed in these boarding houses, they gradually started laying down roots in the city. In the 1890s, settlers started opening businesses catering to Chinese sailors, forming Liverpool’s first Chinatown on the docklands.

After the city suffered heavy aerial attacks during the Second World War, the community moved further inland towards Nelson Street and its surrounding areas, forming the Chinatown we see today.

As part of a redevelopment plan for the area, a Chinese arch was erected on Nelson Street, a homage to the oldest Chinese community in Europe. Standing at 13.5 metres tall, this impressive arch is the tallest of its kind in Europe and the second tallest outside China.

Despite its significance in the earliest days of British Chinese history, Liverpool also offers a glimpse into the prejudice historically levelled against British Chinese communities, with a hidden history that, until the early 2000s, went largely untold.

Despite serving Britain during the Second World War, many Chinese seamen were subjected to significant pay disparities compared to their British counterparts. This led to a strike for rights and equal pay in 1942, stirring up xenophobic sentiments against Chinese workers and labelling them as troublemakers.

This built-up resentment culminated in the mass deportation of Chinese men by the British government after the war, tearing thousands of workers away from their families.

For decades, this event was kept under wraps, leaving wives and children in the dark over where their husbands and fathers had gone, with many children still searching for their fathers today.

Gerrard Street, Soho, London

Attracting more than 17 million visitors per year, the bustling streets of London’s Soho are home to England’s most famous Chinatown. The ever-busy streets are lined with some of the country’s best Chinese restaurants and bakeries, with over 150 businesses and thousands of workers.

Despite its significance now, Gerrard Street is not London’s first Chinatown. In the 1880s, London’s first Chinatown formed in Limehouse in the East End, when Chinese seamen working for British shipping companies, such as the East India Company, started arriving in London for work.

These seamen often stayed in the Docklands, where many Chinese businesses, from restaurants to laundries, provided them with a glimpse of home.

To the outside, however, the area had gained a reputation in the press for its gambling houses and opium dens. This contributed to discrimination directed at Chinese immigrants and a rise in fears of ‘Yellow Peril’, an expression referring to East and South East Asians, particularly the Chinese, as a threat to Western civilisation.

Though these fears were unfounded and steeped in prejudice, they nevertheless led to slum clearance programmes from the local council.

Such programmes displaced many Chinese families in Limehouse and more were driven from the area following the Blitz in the Second World War.

They started relocating towards Soho in the West End, an area known for its low rent and vibrant nightlife. Soho’s long history of welcoming immigrant communities, from Italian to Jewish communities, made it the ideal new home for the displaced Chinese families.

With overseas British soldiers returning after the end of the war in 1945, some had a taste for more diverse cuisines. Consequently, Chinese cuisine became increasingly popular, with many Britons seeking out authentic, flavourful Chinese food.

Chinese workers seized the opportunity to shift their business interests from laundries to restaurants, offering the English a taste of the vibrant flavours of the East.

In the 1970s, the number of restaurants and businesses on Gerrard Street expanded significantly, properly establishing what would become the current Chinatown: a busy neighbourhood in the heart of central London that is still thriving today.

Stowell Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear

Although the Chinatown on Stowell Street in Newcastle was not established until the late 20th century, the story of Newcastle’s Chinese community dates back much earlier.

Some of the earliest Chinese presence in Newcastle can be traced back to the 19th century, marked on distinctive headstones in St John’s cemetery in Elswick, Newcastle. Dating back to 1881, the headstones are dedicated to Chinese sailors who were sent as crew for battleships being built in the Elswick shipyards for the Imperial Chinese Beiyang Fleet, and died from illness.

We recently funded a project run by the Tyne and Wear Building Preservation Trust on behalf of Newcastle City Council at the cemetery, which included engaging with members of the Chinese communities and the production of a new interpretation panel about the sailor graves.

Despite the early presence of Chinese communities, the first Chinese restaurant, Marlborough Café, only opened in 1949. At the time, the Chinese population in the city was only about 30 people, a number that grew over the 20th century, bolstered by post-war migration.

It was not until 1978 that the first Chinese business opened on the street that would become Newcastle’s Chinatown today. The opening of the Chinese supermarket, Wing Hong, was followed by many other businesses, though it took another 10 years before businesses were permitted to have signs in Chinese in addition to English.

An 11-metre Chinese arch, built in China and shipped to Newcastle, was erected in 2005, solidifying Stowell Street as one of the country’s main Chinatowns.

Faulkner Street, Manchester, Greater Manchester

On Manchester’s Faulkner Street sits the second largest Chinatown in the UK and the third largest in Europe. It is a vibrant neighbourhood welcoming a diverse array of cultures.

The first Chinese settlers arrived in Manchester in the early 20th century as an alternative to Liverpool. Filled with 19th-century cotton warehouses, Faulkner Street was known locally as a slum area that was gradually transformed by the opening of Chinese businesses.

Many early settlers participated in the laundry trade, eventually moving to the business of takeaways following the opening of the first Chinese restaurant, Ping Hong, in 1948.

Much like the other Chinatowns in England, Manchester’s Chinese population saw a significant growth from post-war migration, spurred on by the introduction of the British Nationality Act in 1948, which created easier access into the country.

Following the Chinese Communist Revolution and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, huge numbers of refugees fled from mainland China to Hong Kong to escape the unstable politics of the region. This, combined with farmers in Hong Kong displaced by urban sprawl, initiated a swell in Chinese immigration into Britain in the 1950s and 60s.

With an ever-increasing number of restaurants and other businesses such as supermarkets and medicine shops opening in the 1970s, Manchester’s Chinatown gradually became a major cultural hub.

In 1987, an Imperial Chinese arch was specially built in China and shipped to Manchester, celebrating the cultural heritage of the local area’s Chinese community.

Now, Faulkner Street boasts an impressive variety of cuisines, with not only Chinese restaurants, but Japanese, Korean, Nepali, Malaysian, Singaporean, Thai and Vietnamese restaurants lining its streets.

Hurst Street, Birmingham, West Midlands

As one of England’s newer Chinatowns, Birmingham’s Chinatown is a hidden multicultural gem in the Midlands.

Unlike the port cities where Chinese sailors settled before the 20th century, Birmingham did not see large-scale Chinese immigration until post-war migration brought an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong after 1945.

Settling around Hurst Street in the 1960s, the Birmingham Chinese community started as an informal cluster of Chinese businesses, community organisations and social clubs that formed a hub of Chinese culture.

The community grew and thrived over time, until it was recognised as the Birmingham ‘Chinese Quarter’ in the 1980s.

The opening of the Arcadian Centre in 1991 brought a host of restaurants, bars and shops to Birmingham, forming the heart of Chinatown with its 2-tiered courtyard and elegant Chinese architecture. The donation of the 7-storey Pagoda at Holloway Circus by the supermarket chain owners, the Wing Yip brothers, cemented the legacy of Birmingham’s Chinese Quarter.

In May 2024, Birmingham’s Chinese Quarter was renamed Birmingham Chinatown, celebrating the community’s cultural heritage. Unlike other Chinatowns in England, Birmingham does not boast its own paifang, but there have long been plans to install a traditional arch, marking the legacy of Chinese culture in Birmingham.

Written by Steph Chan

Further reading

Leave a Reply