William I, also known as William the Conqueror, was the first Norman king of England, who reigned from 1066 to 1087.

Before this, he was the Duke of Normandy from 1035. When the Anglo-Saxon English king, Edward the Confessor, died in 1066, William set his sights on invading England and expanding his power.

Invading England wasn’t going to be easy, and success was not guaranteed. England was a bigger, better-organised, and more prosperous country than Normandy.

So, let’s explore how and why William set his sights on conquering England.

Who was William the Conqueror and his family?

William, born to Robert I of Normandy and his mistress Herleva, was long known as ‘William the Bastard’. Even after his victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 earned him the title ‘William the Conqueror’, rivals still whispered the old name behind his back.

William grew up in Normandy in France (named for its Norse rulers), a land won by his Viking ancestor Rollo, who traded raids for a duchy in the early 900s.

Orphaned at 7 years old, William inherited the title of Duke and survived a chaotic youth to secure his rule. His marriage to Matilda of Flanders (the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Flanders) in the 1050s cemented a crucial alliance with his powerful neighbour.

Why did William the Conqueror invade England?

After King Cnut died in 1035, England experienced a tumultuous struggle for power between his sons, Harthacnut and Harold Harefoot, Queen Emma, and the influential Godwin family.

Eventually, Harthacnut ascended to the throne. However, his unpopularity due to his harsh rule prompted him to invite his exiled half-brother, Edward the Confessor, back to England. When Harthacnut died mysteriously in 1042, Edward became king, restoring the Saxon House of Wessex.

Tensions escalated between Edward and the powerful Godwin family. King Cnut the Great made Godwin Earl of Wessex, one of the most powerful earls in England, giving the family immense influence and power. Godwin secured a marriage between his daughter, Edith, and King Edward, thereby strengthening his influence.

However, Edward’s relationship with his cousin, William of Normandy, also strengthened. William ultimately invaded England in 1066, believing Edward had assured him he would be his successor if his marriage produced no heirs.

In 1064 or 1065, Harold Godwin, the eldest son in the Godwin family and Edith’s brother, travelled to the Continent and was captured and handed over to William. Harold allegedly swore an oath (possibly under duress) to honour William’s claim to the English throne when Edward passed.

Edward the Confessor died on 5 January 1066 and was buried on 6 January in Westminster Abbey in London. On the same day as the funeral, his brother-in-law Harold Godwin hastily crowned himself king despite his oath to William.

The Pope did not recognise Harold’s coronation, and William portrayed Harold as an oathbreaker to win over the Pope. With the Pope’s support, William justified his invasion and staked his claim to the English throne.

When did William plan to invade England?

Problems arose quickly for King Harold. In response to raids by his estranged brother, Tostig, in April and May of 1066, Harold mustered a large force of up to 16,000 men, initially stationed at Sandwich, in present-day Kent.

Unable to sustain them indefinitely, he dispersed his troops along the south coast. William was now aware of Harold’s logistical strain and was waiting for the right moment.

On 8 September 1066, Harold disbanded most of his army, assuming William would not invade this late in the season. Days later, he received dire news.

Tostig had returned, this time with the formidable Norwegian king, Harald Hardrada. With 200 ships and 8,000 warriors, they landed in Yorkshire and camped at Riccall.

Meanwhile, William attempted to sail but was forced to shelter at St Valery due to rough seas. He may have learned that Harold’s forces were dismissed, and now was the best time to invade.

Leaders in York saw little hope of resisting and negotiating with Tostig and Hardrada. Hostages were exchanged, and the Anglo-Danes of York agreed to support the Norwegians. The invaders withdrew to Riccall to rest, with a crucial meeting planned at Stamford Bridge.

When did William the Conqueror invade England?

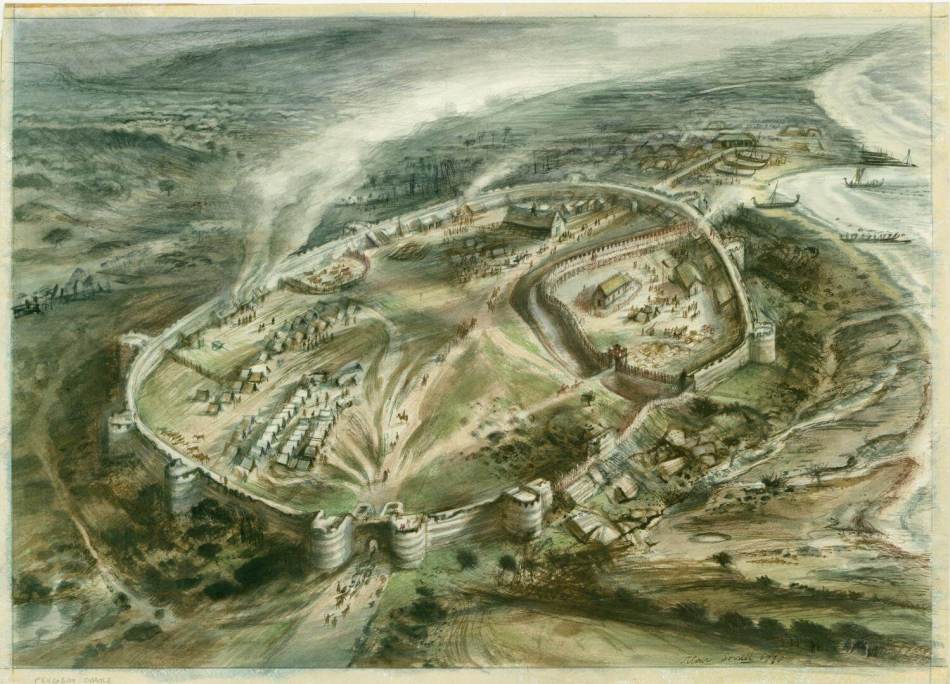

Finally, the winds shifted, and William seized his chance. He crossed the English Channel and landed at Pevensey in present-day East Sussex on 28 or 29 September 1066. The site provided a secure harbour and a Roman fort, which was fortified as a base.

His forces swiftly advanced to Hastings, where they constructed a wooden and earth castle and prepared for the coming conflict.

On 1 October 1066, King Harold was informed that William had landed in England. At the time, Harold was in York, likely having stern conversations with the city authorities for capitulating too quickly to Hardrada and ensuring the city remained loyal. Following this, Harold rode south with his core troops.

Meanwhile, the Normans were raiding and burning, including Harold’s lands. They did this partly to sustain themselves and to provoke Harold into a direct battle before he could gather a sufficient force in the South.

On 11 October, Harold departed for Hastings, mustering whatever troops he could. He may have set off prematurely, motivated by the destruction of his own lands and possibly hoping to launch another surprise attack by moving quickly. His forces assembled at the “grey apple tree” on Senlac Hill near Hastings and made camp.

What happened at the Battle of Hastings?

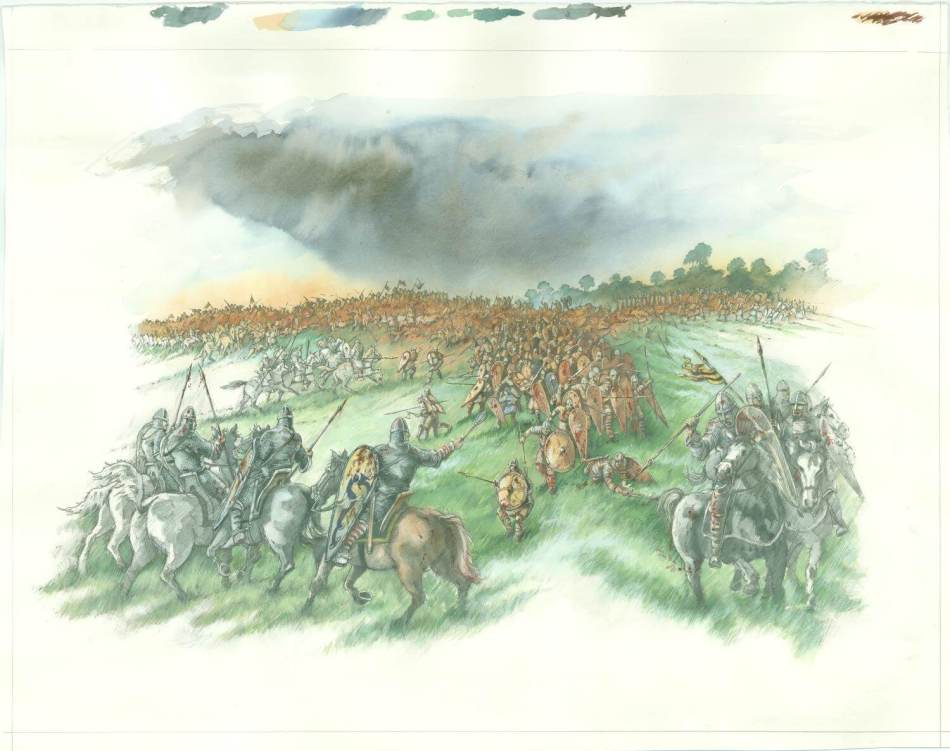

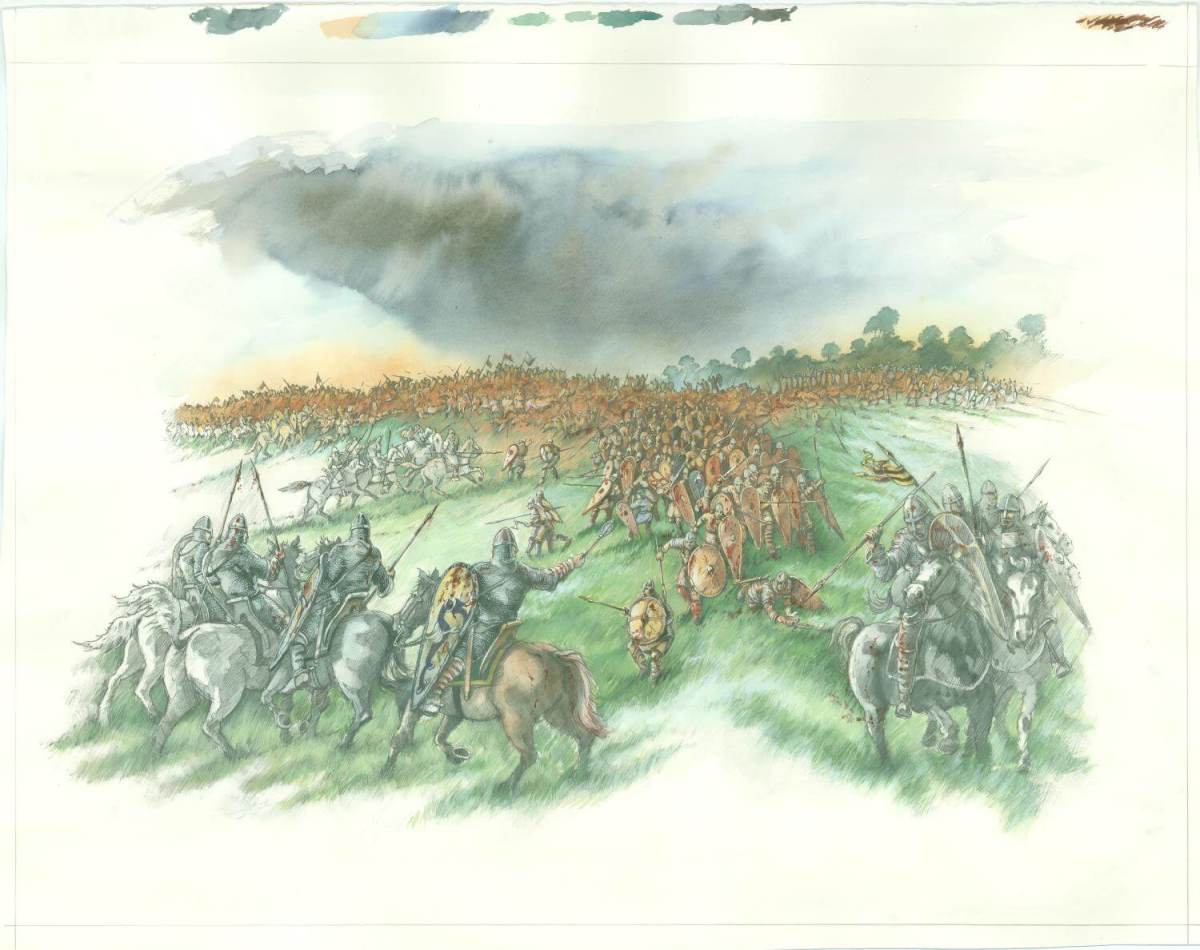

The Battle of Hastings began on 14 October 1066, with the English forming a solid defensive line atop Senlac Hill, where Battle Abbey now stands. Below them, the Normans assembled in three ranks: archers in front, heavy infantry behind them, and cavalry at the rear.

The Norman archers struck uphill, but the steep incline diminished their impact. Norman infantry charged but were repelled by the English shield wall, while cavalry struggled to break the formation. The elite Saxon housecarls inflicted heavy casualties.

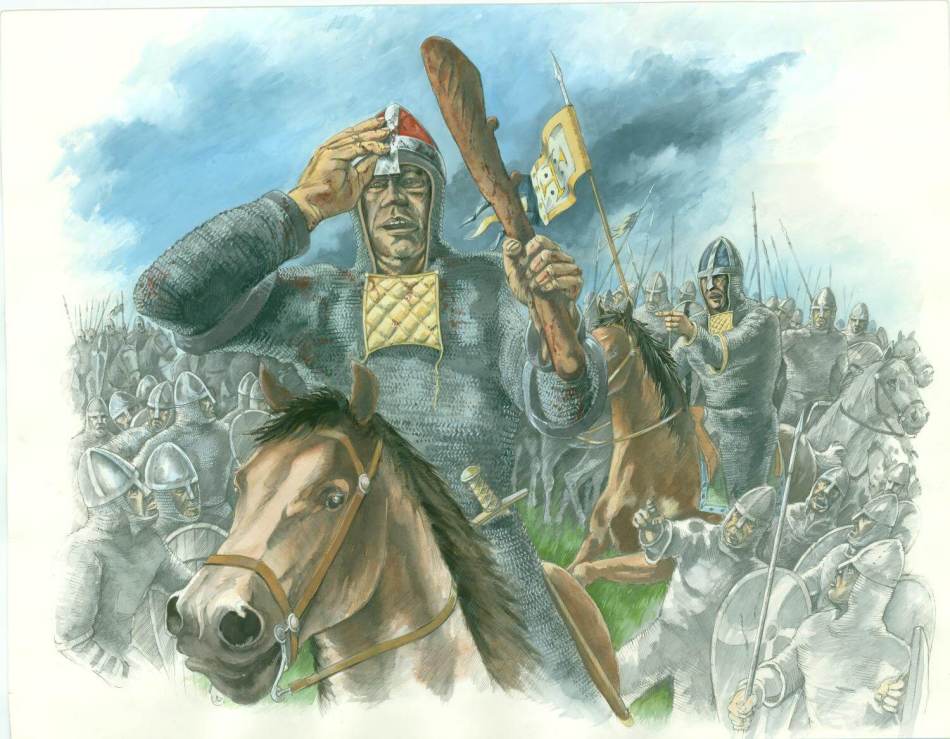

On the Norman left flank, some troops broke and fled, leading to rumours that William had been killed. He soon revealed himself, rallying his men.

Some of Harold’s less disciplined soldiers chased the retreating Normans, creating gaps in the English line that William exploited.

Why did William win the Battle of Hastings?

As the English ranks weakened, the Norman assaults increased. Harold was killed during the battle.

Accounts vary, suggesting he was struck by an arrow or killed by a Norman soldier. His body was reportedly so mutilated that only his former common law wife, Edith Swan-Neck, could identify him.

With their king dead, the English line collapsed. Many fled, while others were killed by Norman cavalry.

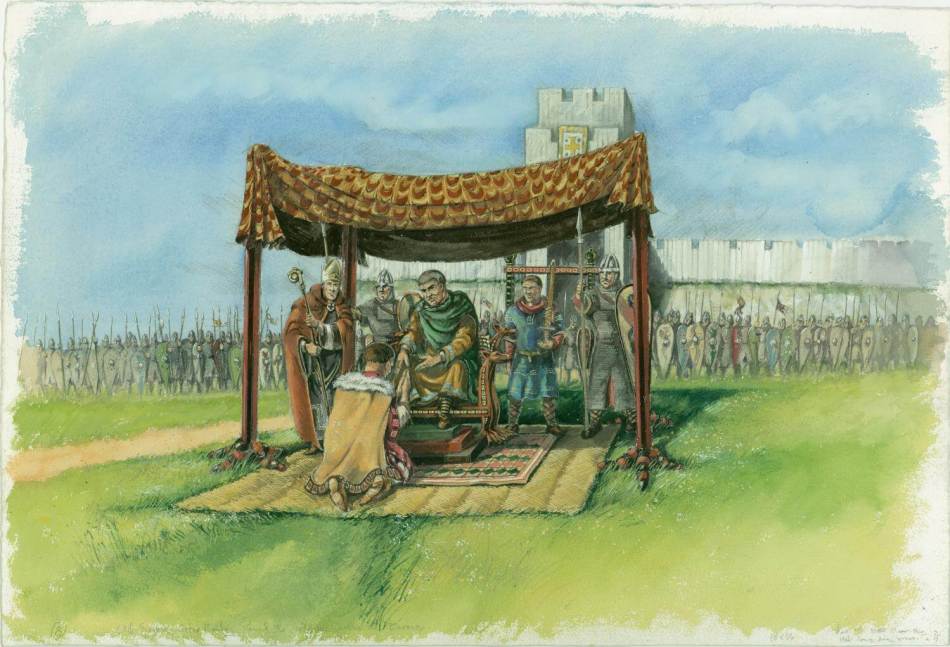

English leaders in London proclaimed Edgar the Aetheling king. He was the last male survivor of the official dynasty of Wessex, and the grandson of a previous king, Edmund Ironside. However, the Normans required a coronation to recognise him. William seized the moment, capturing Dover and ravaging southern England.

Key figures, including Archbishop Stigand, abandoned Edgar’s cause. By December 1066, William’s victory in the south was complete, and he was crowned King of England on Christmas Day.

What happened during William the Conqueror’s reign?

Initially, William was more conciliatory in his takeover than Cnut had been decades earlier. He attempted to reward his men with land and win over some English nobles.

However, he charged Saxon landowners to continue holding their land. The properties of those who died at Hastings or participated in revolts were granted to Normans. This policy ultimately failed, as it was still too harsh, leading to rebellions and distrust.

During these rebellions, the north of England, especially Yorkshire, suffered terribly. William’s forces laid waste to large areas, burning villages and crops and inflicting terror on the population.

Thousands starved in the resulting human-made famine, were killed or fled to other parts of the country. Consequently, there was a widespread replacement of landowners by Normans or allied French lords, and churchmen were likewise replaced.

There was a part of the country that William didn’t conquer at all: Cumbria. At that time, Cumbria was the successor to the Kingdom of Strathclyde and stretched on both sides of the Solway Firth, roughly from Govan to Penrith.

It was not considered part of the core English kingdom. It was almost independent, but was being squeezed by both Anglo-Saxon England and Scotland.

The majority of the population spoke a type of Welsh Celtic language, along with some Anglians and a significant number of Norse Viking settlers. William had so much on his plate subduing Yorkshire that he left Cumbria alone. It was left to his son, William II, to finish that job later on.

Rumours of an invasion by the King of Denmark led William to assemble a vast and expensive mercenary force to defend England. As he needed to know the wealth of the land to pay for this army, he had the great record known as the Domesday Book compiled between 1085 and 1086.

With changes in land ownership and leadership in the church, William and his French followers made their mark on England’s buildings. They constructed castles to hold down the country, and they built or rebuilt churches that they thought were more fitting for the new order, including a castle at Windsor, Durham Castle, The White Tower, Dover Castle and one on the site of York‘s current Clifford’s Tower.

How did William the Conqueror die?

In 1087, William was fighting with France and was injured, either in battle or by the pommel of his horse’s saddle. He died in Rouen, Normandy, on 9 September 1087 and was buried in the Abbey of Saint-Étienne in Caen, Normandy, which William had founded in 1063.

According to some accounts from the time, his body was mistreated after his death, and due to the internal damage caused by the injury, his swollen belly is rumoured to have exploded.

Shortly before he died, William hastily appointed his second son, William Rufus, the next King of England.

William’s reign undoubtedly changed England, and it greatly influenced religious reform, language, and the physical landscape of the land.

Further reading

Leave a Reply