For centuries, England has had a rich tradition of decorating interior walls with painted imagery. The paintings could depict tales from the Bible and offer moral warnings to local church congregations, almost all of whom were unable to read or write before education became widely available.

Wall paintings first appeared in England during the Roman period (AD 43 to 410), yet only fragmentary remains of them have been found to date. However, many remarkable ecclesiastical examples have been discovered from the centuries following the Norman Conquest in 1066.

Here, we examine some striking and important examples from the Middle Ages to the 19th century.

Medieval ecclesiastical wall paintings

During the Middle Ages, murals or the far rarer frescoes (named after their painting techniques and generically referred to here as wall paintings) found some of their greatest decorative expression in England’s medieval churches and other ecclesiastical sites.

For around 8 centuries, religious wall painting (along with decorative patterning and occasionally including Latin texts) was ubiquitous, from humble rural churches and chapels to monasteries, cathedrals and palaces.

Although many paintings now survive only in faded or illegible form or as fragments, in the Middle Ages, church walls were ablaze with imagery and colour.

Sometimes, this was designed to enhance the architectural features of the church, but the most elaborate pieces brought to life vivid narrative subjects that included tales from the Bible, the Saints, and the Day of Judgement, with the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary among the most frequently depicted.

The life of Christ

Medieval wall paintings in parish churches were created mostly using earth pigments such as red and yellow ochre, lime and charcoal.

During this period, church interiors were probably mostly painted by travelling groups of journeyman artists. Works were almost always painted directly onto dry plaster walls (known as ‘secco’) using badger bristles and hog’s hair, or squirrel hair for fine detailing.

The paintings could offer powerful devotional imagery and moral warnings to local congregations, almost all of whom were unable to read or write, teaching a Christian understanding of the world.

Scenes from the Bible

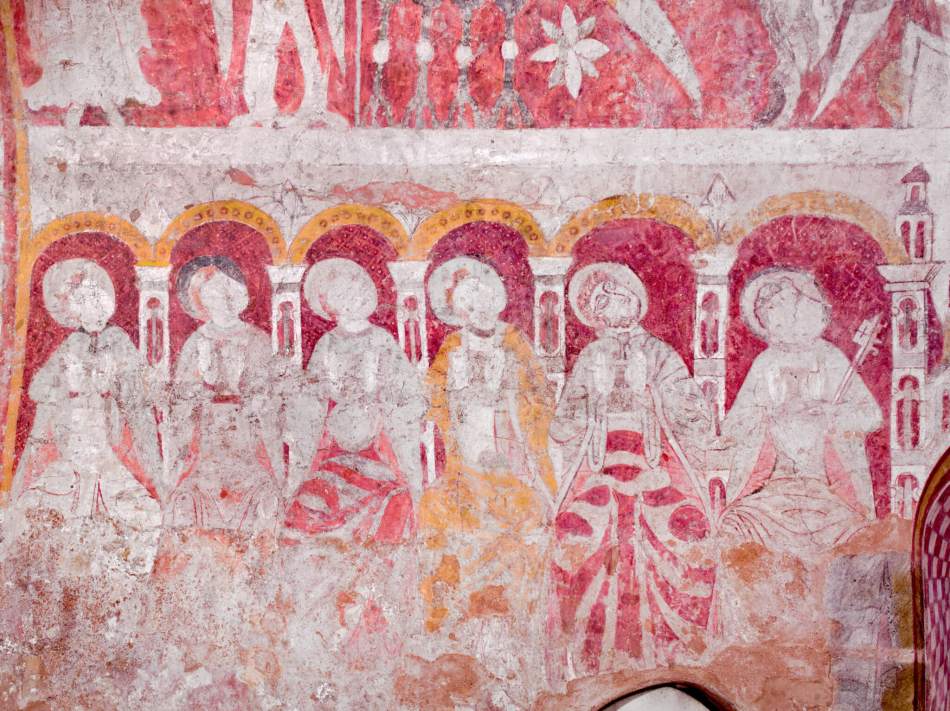

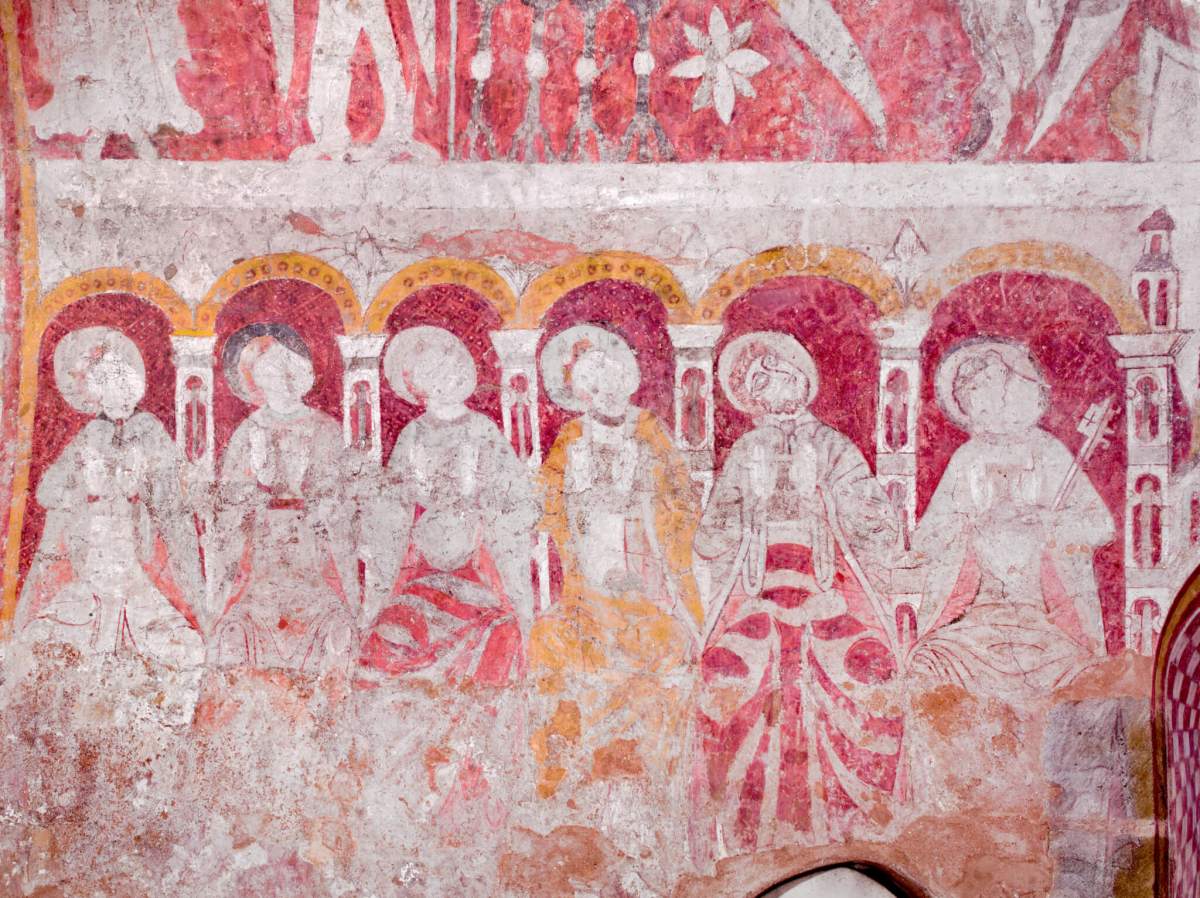

St Botolph’s Church in Hardham contains a near-intact scheme of early 12th-century wall paintings. These include the finest surviving examples of the Anglo-Norman style of this period on either side of the chancel, with stylistic links to the Bayeux Tapestry and contemporary Norman manuscripts.

St Botolph’s is one of a small group of churches with paintings believed to be the work of a single workshop of artists, possibly resulting from the churches’ patronage by the Cluniac Priory at nearby Lewes.

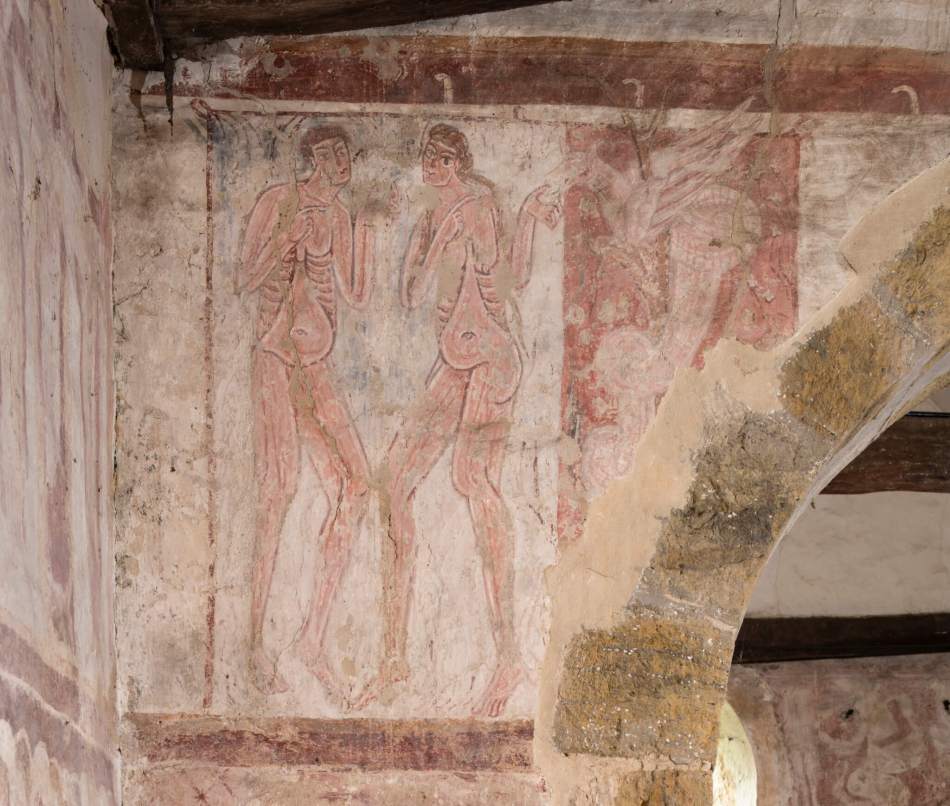

This one below is one of several paintings at St Agatha’s Church in Easby depicting scenes from the Bible.

The lives of saints

Many church wall paintings depict the lives of saints. Such saints were seen as advocates in heaven for the faithful on earth. They were believed to have a capacity to heal, to help with pregnancy and protect against disasters. Those who were martyred became popular pictorial subjects in many parish churches across the country.

The murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1170 profoundly shocked the whole of Christendom. His martyrdom ensured he was quickly raised to sainthood, becoming one of the most significant saints of the Middle Ages.

Others favoured saints whose images appear on the walls of many English parish churches include St Christopher, patron saint of travellers, executed in the 3rd century because he refused to sacrifice to pagan gods.

Saints such as St Margaret also feature, who refused to renounce Christianity, and St Katherine, who converted hundreds to Christianity and was martyred in the 4th century, aged 17.

Images of St George, an early Christian martyr believed to be a Roman officer, can be traced as far back as the 9th century, 500 years after his death, with later legends of his slaying of the dragon coming to symbolise the struggle between good and evil.

During the Middle Ages, St George was also venerated as one of the ‘14 Holy Helpers’: saints who could protect the population against epidemics such as the plague or leprosy.

The Day of Judgement (Last Judgement)

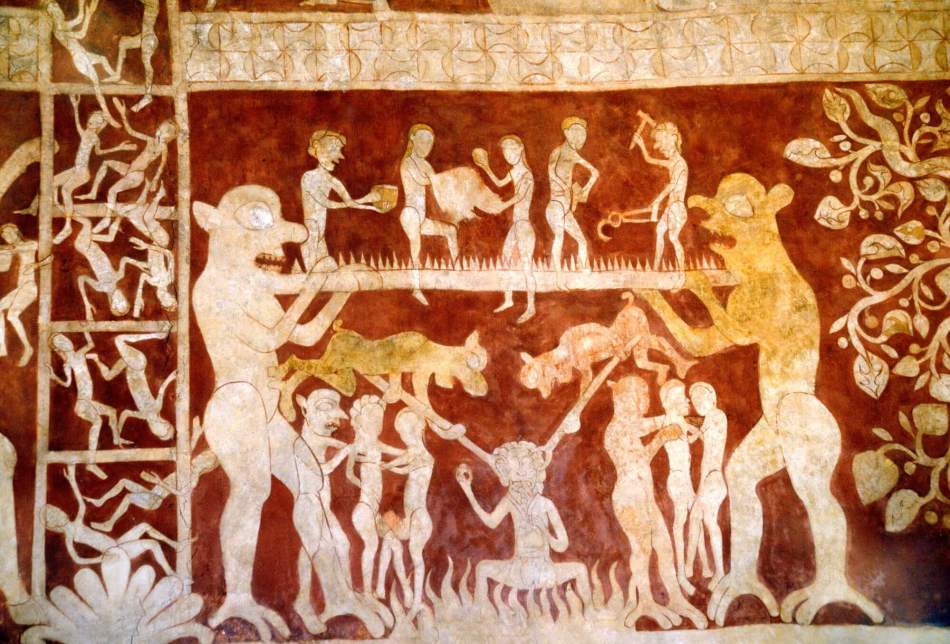

The immense painting below is featured in St Thomas’s Church in Salisbury. It was limewashed over during the Reformation in the 16th century. Until then it had served as a reminder to medieval congregations of the terrifying consequences of straying from the path of true religion.

Christ sits in judgement with the 12 Apostles beneath his feet. Lower left shows open graves with angels taking the naked blessed dead up to Heaven, while Satan presides in the lower right, where devils send sinners, including a bishop, into the Jaws of Hell, represented by a monstrous gaping dragon.

Such shocking imagery emphasised the moral that God will judge everyone equally according to their sins.

The Ladder of Salvation is an important example of the Day of Judgement, including souls falling from a ladder, and symbols of the 7 deadly sins including Lust (a man and woman embracing) and Avarice (a man hung with bags of money, coins pouring from his mouth, being held on prongs by 2 devils).

This features in the St Peter and St Paul Church in Chaldon, and is early 13th-century in origin.

Wall paintings in religious institutions

Westminster Abbey

Many English cathedrals, such as Westminster, Canterbury, Rochester, Norwich, Winchester, Durham, and St Albans, are home to significant medieval wall paintings.

Westminster Abbey’s St Faith wall painting is a good example of the use of colour in the medieval period, with her dark green tunic and a rose pink mantle against a vivid vermilion background.

Unlike the parish churches, which had to settle for using cheaper earth pigments, wealthy institutions could afford fine colours derived from minerals such as vermilion from cinnabar, blue from azurite or lapis lazuli, and green from malachite. Gilding was used, along with gold effects created from lead and tin.

St Albans Cathedral and Abbey

St Albans Cathedral has the most extensive set of medieval wall paintings of any English cathedral. Most would have been painted by highly skilled professional artists using the finest materials.

Images of the Crucifixion appear on 5 of the cathedral’s giant Norman piers. Other paintings include portraits of saints, the Apostles, and scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary.

The former Benedictine Abbey was completed in 1115. During the Reformation in Britain (1533 to 1603), the Abbey was closed and much of it destroyed. In the 19th century, wealthy Victorian benefactors paid for its restoration and, in 1877, what had previously been a parish church was designated as a cathedral.

In the Victorian era, limewash applied during the Reformation was removed, revealing the extraordinary paintings.

Carthusian monastery, Coventry

The Charterhouse in Coventry features England’s only surviving wall painting in a Carthusian monastery (a monastic order with an emphasis on solitary prayer).

Founded in 1381, the building’s earliest surviving painting dates from the early 15th century and shows the Crucifixion in the centre with the Virgin Mary and St Anne.

After Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries (1536 to 1541) as part of the Reformation and broke from Rome’s papal authority, Charterhouse was converted to a house and passed through many hands before the building and its magnificent wall paintings were restored and opened to the public in 2023.

Wall paintings during the Reformation and English Civil Wars

For hundreds of years, England and the Continent shared a common Catholic liturgy, using Latin as the language of religion.

But in the 16th century, a religious revolution, the Reformation, swept across Europe, challenging the doctrine and language of the Catholic Church and introducing Protestantism to England.

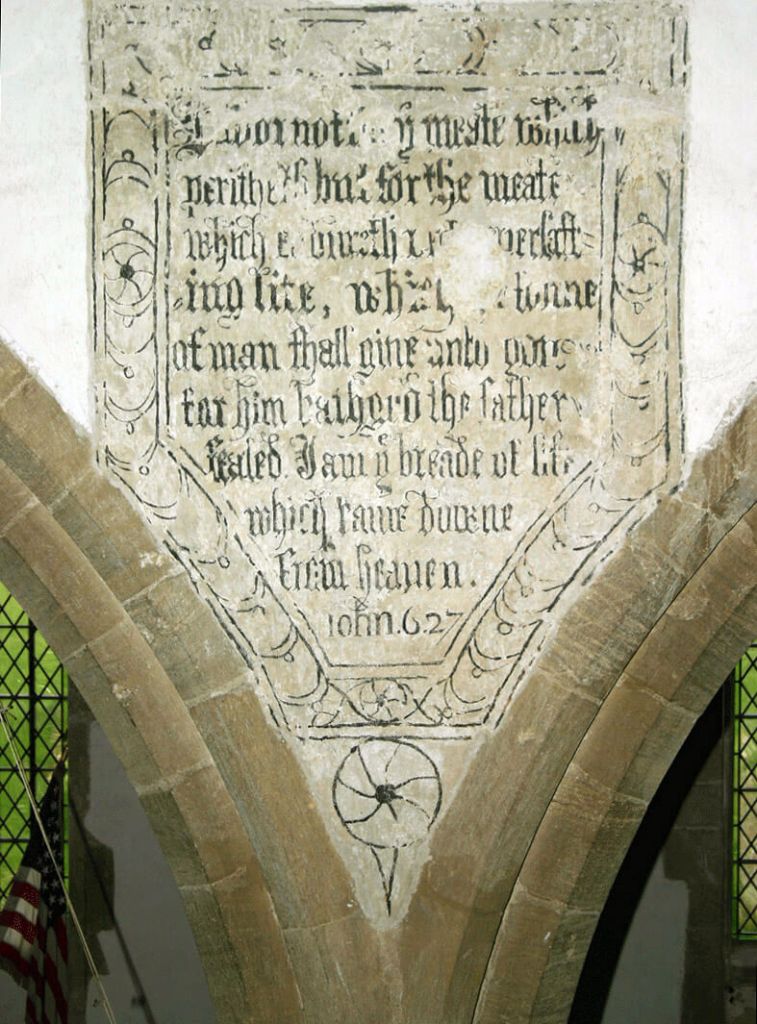

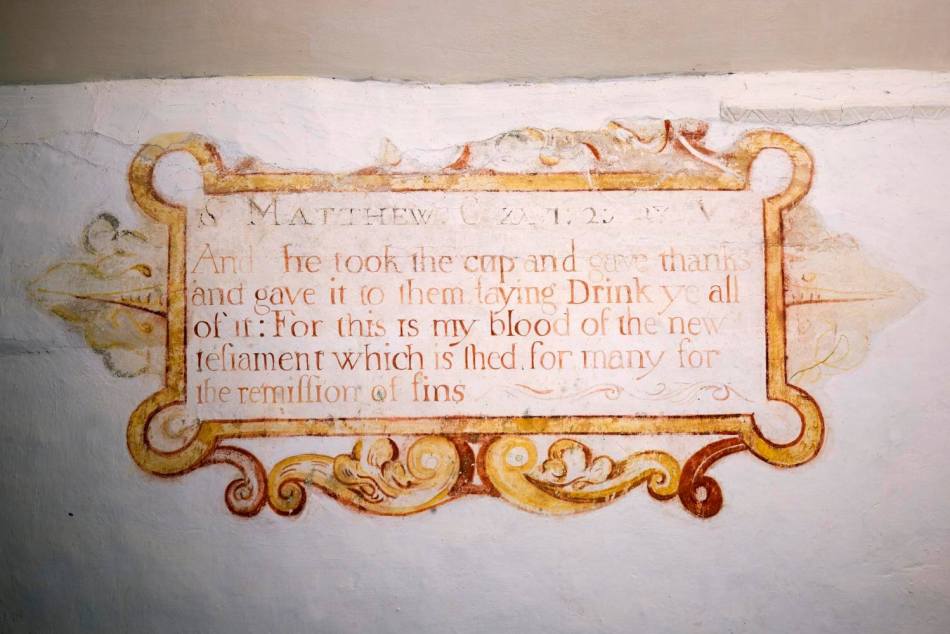

During the English Civil Wars (1642 to 1651), most ecclesiastical murals were viewed as idolatrous and sacrilegious. Such paintings were commonly lime-washed, plastered over or covered up, often replaced by ‘improving’ holy texts and scriptures. This reflected the Protestant belief in the primacy of the word of God over images.

Such texts and scripture extracts continued the tradition of painted wall surfaces in churches, however. Some could be quite decorative, set in painted architectural features, such as examples at All Saints Old Chapel in Leigh, Wiltshire.

Wall paintings rediscovered

It is fortuitous that the methods used to cover murals in the 16th and 17th centuries preserved some original wall paintings, ready for discovery in the centuries that followed.

The wall paintings decorating the stone walls of Eton College’s St Mary’s Chapel were created by at least 4 master painters between 1479 and 1487. The chapel’s north side depicts a sequence of miracles performed by the Virgin following her death. The south side portrays a popular medieval story.

The college barber limewashed all the wall paintings over in 1560 after an edict from the Protestant Church that banned the celebration of miracles. Forgotten for 300 years, they were rediscovered in 1847, but not properly revealed until the removal of the choir stall canopies in 1923, when they were restored.

19th century: destruction and rebirth

The tradition of church wall painting waned over time to the extent that, by the 18th and 19th centuries, ancient wall plaster and its historic medieval decoration were often being stripped off during radical restorations, leaving the plain white walls that are a familiar feature of many parish churches today.

Alongside this, the New Churches Act of 1818 aspired to address the problem of an inadequate number of Anglican churches for growing urban populations, providing £1 million for building new churches.

By the start of Queen Victoria’s reign in 1837, 134 had been constructed. This was accelerated from then on by a religious revival and a growing interest in medieval Gothic architecture and ritual.

Many newly constructed churches, and some existing churches, were painted with elaborate religious iconography, inspired by and continuing the rich heritage of wall painting in England’s medieval period, and later influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement.

In parallel, wall paintings in some medieval parish churches were subject to well-meaning but overzealous Victorian restoration. The 12th-century Copford Church in Essex is one example.

In 1871, painter Daniel Bell was commissioned to repaint the original. He introduced his own additions, including painting a crown on Christ’s head, adding symbols carried by the Apostles, tidying up outlines and altering facial features.

Specialist conservation work was undertaken between 1988 and 1993, with Bell’s over-painting retained as part of the church’s evolving decorative religious history.

At St Andrews Church in Roker, Sunderland, designed by E S Prior and sometimes referred to as the ‘Cathedral of the Arts and Crafts movement’, the chancel has a striking decorative scheme designed by MacDonald Gill, which was added between 1927 and 1929, continuing the tradition of wall paintings well into the 20th century.

The 20th century generally also saw wider recognition of the importance of surviving medieval and later wall paintings, with conservation evolving rapidly to ensure their long-term survival.

Further reading

Leave a Reply