Stonehenge has captured people’s imaginations for centuries as one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments. But England has hundreds of other ancient sites, each with its own story.

These monuments, scattered across the landscape from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic periods, offer a glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and cultures of our prehistoric predecessors.

Here, we’ve split them into smaller groups, including:

Stone circles

Stone circles are scattered across England, particularly in the south-west and north-west.

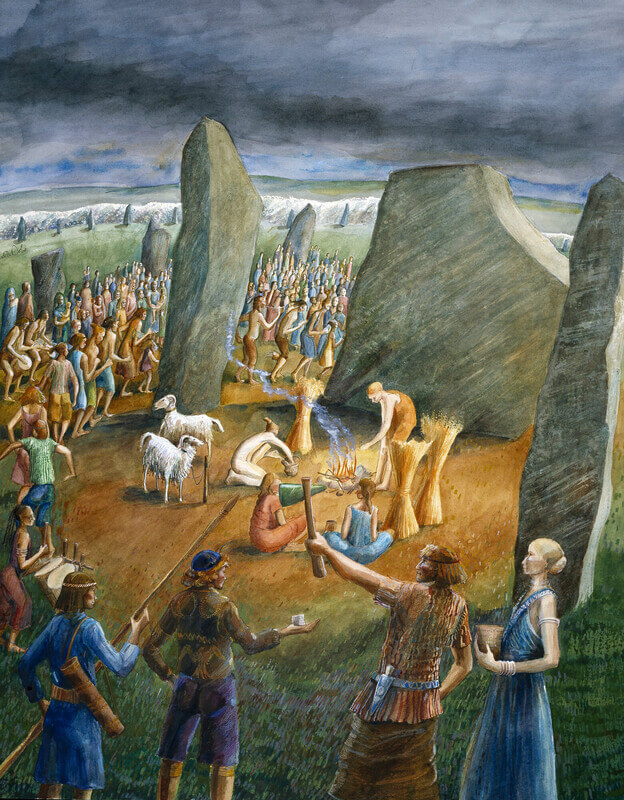

Their exact purpose is unknown, but they likely held ritual significance. Some may be linked to burials, while others may have tracked seasonal changes, marking events such as the midsummer sunrise or midwinter sunset.

Stonehenge and Avebury, Wiltshire

Stonehenge is the world’s most famous prehistoric monument, known for its massive megaliths, intricate design and carefully shaped stones.

But just as remarkable is nearby Avebury, home to the largest prehistoric stone circle in the world, surrounded by a massive bank and ditch.

These sacred sites, along with the numerous other Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments in their surrounding landscape, offer an incredible glimpse into the lives and beliefs of prehistoric people.

Long Meg and Her Daughters stone circle, Cumbria

The Long Meg and Her Daughters stone circle is located above the River Eden in Cumbria, near Penrith. It features 69 stones, with one large stone, Long Meg, standing apart.

Local legend says Long Meg was a witch turned to stone for dancing with her daughters on the moor (and breaking the Sabbath).

Long Meg is adorned with ancient carvings, including cup-and-ring marks, spirals, and other symbols thought to have religious significance.

These carvings, along with findings from other stone circles, suggest that the site was important for rituals and gatherings during the Late Neolithic period, between around 3000 and 2500 BC.

The Rollright Stones, Oxfordshire

The Rollright Stones are a fascinating group of ancient monuments, including a stone circle, a portal dolmen (a type of megalithic tomb), a standing stone, a round cairn, and a ditched round barrow.

Located on the Oxfordshire-Warwickshire border near Little Rollright, these sites were among the first protected by the 1882 Ancient Monuments Protection Act.

The most famous feature is the King’s Men stone circle, one of the best-preserved in Britain. About 70 of its original 100 stones remain standing. Legend says the stones were once a king and his army, turned to stone by a witch’s spell.

Standing stones and monoliths

Standing stones don’t have to be part of stone circles. These ancient monuments from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age are often associated with rituals and ceremonies.

Their exact purpose is unclear, but they may have marked pathways, territories, graves, or gathering places. Many show signs of ritual use and are sometimes associated with deposits, including cremation burials.

These stones are found in various regions, with notable clusters in Cornwall, the North York Moors, Cumbria, Derbyshire, and the Cotswolds.

The Rudston Monolith, East Riding of Yorkshire

The Rudston Monolith is the tallest standing stone in England at nearly 8 metres. Remarkably well-preserved, it still stands in its original location within a churchyard.

Excavations by Sir William Strickland in the 18th century suggested that the Rudston Monolith might be just as deep underground as it is tall above the surface.

The Devil’s Arrows, North Yorkshire

Dating from the Late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age, these 3 stones near Boroughbridge stand roughly in a line. The tallest stone, standing at almost 7 metres, is surpassed only by Rudston among the ‘menhirs’ of the UK.

The name comes from a legend about the Devil throwing stones (or arrows) at the Christian settlement of Aldborough from Howe Hill, but they fell short and landed in a line.

In the 18th century, writer and antiquary William Stukeley noted that an annual fair dedicated to St. Barnabas (but actually celebrating the Summer Solstice) was once held near the stones.

Long barrows and chambered tombs

Long barrows, built during the Early and Middle Neolithic periods (between approximately 3900 and 3000 BC), served as early burial sites for Britain’s first farming communities. These large earth or stone mounds, often with side ditches, are among the oldest landmarks still visible today.

Excavations suggest they were used for communal burials, sometimes with only selected bones inside. Some sites show evidence of earlier rituals, suggesting their long-standing significance to local communities.

Uley Long Barrow, Gloucestershire

Uley Long Barrow, also known as Hetty Pegler’s Tump (after 17th-century landowner Hester Pegler), is a striking Neolithic burial mound, approximately 5,000 years old, that overlooks the Severn Valley.

The passageway leads from the forecourt to a series of internal chambers. Over time, between 15 and 20 skeletons have been found here.

Coldrum Megalithic Tomb, Kent

Coldrum Megalithic Tomb is Kent’s best-preserved megalithic long barrow, named after the now-demolished Coldrum Lodge Farm. The name ‘Coldrum’ may mean ‘a place of enchantment’.

First used probably between 3985 and 3855 BC, the long barrow is around 1,000 years older than Stonehenge. Bones from at least 17 people have been discovered here, with some remains showing evidence for post-mortem dismemberment.

Round barrows

Round barrow cemeteries date back to the Early Bronze Age (between about 2200 and 1500 BC) and consist of groups of up to 30 burial mounds, often surrounded by ring ditches.

The mounds, made of earth or rubble, covered single or multiple burials. Many have been levelled by farming and only the infilled ring ditches survive, visible from the air as cropmarks or soilmarks. These cemeteries evolved over centuries, with some reused for burial in the early medieval period.

They vary in layout and burial practices, often featuring different types of round barrows, reflecting the changing traditions of the communities that used them.

Oakley Down round barrows, Dorset

Oakley Down barrow cemetery, situated on Cranborne Chase, features Bronze Age burial mounds in an area rich in archaeological significance.

Known for its concentration of Neolithic and Early Bronze Age sites, Cranborne Chase is one of England’s most significant prehistoric landscapes. Its preservation is largely due to its status as a Royal Hunting Ground, with strict land-use laws that lasted until 1830.

Excavations of many of the Oakley Down barrows in the early 19th century uncovered inhumation and cremation burials accompanied by fascinating grave goods, including amber, glass, and faience beads, as well as bronze daggers.

The Devil’s Jumps round barrow cemetery, West Sussex

The Devil’s Jumps round barrow cemetery is a site with 7 burial mounds, arranged in a linear formation, including rare bell barrows and more common bowl barrows, over 10,000 of which are recorded across Britain.

Bell barrows, primarily found in Wessex, were often used for burials, containing grave goods like weapons and jewellery. Bowl barrows, with over 10,000 recorded in Britain, were more widely used.

The significance of the different types is unclear, but bell barrows are often large monuments, and the berms would have allowed gatherings inside the ring ditch.

Hillforts

Hillforts are some of England’s most impressive ancient sites, with their towering earthworks and hilltop locations offering a glimpse into life in the Iron Age over 2,000 years ago.

Built between 900 and 100 BC, these defended sites were surrounded by banks and ditches, often on ridges or hilltops. Some, like ‘marsh forts,’ were even built in low-lying areas.

More than 3,000 hill forts exist across Britain. Some were later reused, sometimes as medieval castles, making it harder to see their earlier use.

Maiden Castle, Dorset

Maiden Castle near Dorchester, Dorset, is one of the largest and most complex Iron Age hillforts in Britain, with 3 massive banks and 2 ditches enclosing the hilltop, which was intensively occupied. But it wasn’t the first monument on the hill.

Approximately 5,500 years ago, during the early Neolithic period, people cleared the hilltop and built an oval enclosure with segmented ditches, making it one of Britain’s earliest monuments.

This causewayed enclosure was likely a gathering place for special activities, such as flint axe-making. Later, a huge, long mound known as a bank barrow was constructed across the infilled ditches of the enclosure, stretching nearly 550 metres.

Though barely visible today, it may have honoured ancestors or marked a boundary in the landscape.

Hembury Fort, Devon

Hembury is an Iron Age hillfort situated near Payhembury, Devon, with layers of history dating back nearly 6,000 years.

As at Maiden Castle, Early Neolithic people built a causewayed enclosure here, likely for economic, social, and ceremonial use. The visible earthworks, comprising 3 closely-set ramparts, were added in the Middle Iron Age and built over earlier defences.

Excavations in the 1980s revealed even more of Hembury’s story, including a brief Roman reoccupation around AD 50 during their conquest of the south-west. Research continues to uncover its fascinating and complex past.

Prehistoric caves and rock shelters

Caves are natural underground spaces that humans have used for shelter, burial, storage, and even ritual purposes.

Most caves in England are found in limestone areas, such as the Mendips, the White Peak, and the north Pennines. These caves formed over thousands of years as rainwater slowly dissolved the rock. Some are small, while others are vast networks of tunnels and chambers.

As they open into the unknown, caves have long inspired myths and legends, blending the natural and supernatural.

Thor’s Cave, Staffordshire

Thor’s Cave is a natural cavern in the Peak District, set high in a limestone crag. Its massive arched entrance is easy to spot from the Manifold Way below, but exploring requires caution as the steep paths can be slippery.

Thor’s Cave has a rich history, with evidence of human occupation dating back around 11,000 years. People used it throughout the Stone Age, the Iron Age and even the Roman period.

Archaeologists have uncovered stone tools, pottery, amber beads, bronze items, and the remains of at least 7 individuals from Thor’s Cave and its neighbour, Thor’s Fissure Cavern.

Victoria Cave, North Yorkshire

Victoria Cave is a limestone cave near Settle, tucked into the hillside. It has 3 interconnected chambers and 2 entrances, with a smaller fissure nearby that’s part of the same system.

Excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries uncovered remarkable finds, including flint tools and a rare decorated antler rod from the Late Upper Palaeolithic period. The cave also holds a rich collection of animal remains dating back 100,000 years.

Rock art

In Britain, ‘rock art’ refers to prehistoric carvings spanning at least 10,000 years before the Roman period.

Styles range from life-like Palaeolithic animals at Creswell Crags to Bronze Age axe-head carvings at Stonehenge. However, the term mainly applies to abstract carvings dating from around 3800 BC to 1500 BC, found across northern and Atlantic Europe on natural outcrops, cairns, and standing stones.

With over 5,000 sites in Britain, these motifs likely held sacred meanings rather than having purely aesthetic purposes. As they do not depict recognisable figures or constellations, there are many theories about what they represent.

Roughting Linn, Northumberland

Roughting Linn has northern England’s largest carved rock, featuring around 60 motifs on a prominent outcrop that resembles a cairn.

What makes Roughting Linn special is its variety of patterns. The carvings feature classic cup-and-ring designs, delicate, flower-like shapes, and intricate, interconnected grooves.

Ilkley and Rombalds Moor, West Yorkshire

The moors around Ilkley, Silsden, Keighley, and Menston are rich in history, with ancient burial cairns, enclosures, and stone circles. However, what makes them special are the rock carvings from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age.

Sites like the Badger Stone and Hanging Stones feature mysterious patterns of cups, rings, and grooves carved into the rock. Many are found near ancient burial sites or on high ground with views over the Wharfe Valley.

If you want to discover more about England’s prehistoric sites, check out:

Further reading

Leave a Reply