Over the past 2 centuries, England’s towns and cities have experienced unparalleled growth, which has led to the creation of the suburbs on the edge of urban areas where most of us now live.

Due to the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century and the need for more housing for a soaring population, suburban development now constitutes a significant proportion of the historic built environment.

Following recent research by Historic England, a new book, ‘England’s Suburbs 1820-2020,’ featuring over 250 illustrations, aims to explain and celebrate the wealth of our suburban heritage.

It looks at those areas formed by the growth of a town or city that are neither urban nor rural and at ‘outposts’ of suburbia served by mass transport.

One way to understand the suburbs is to examine their creation and planning, their characteristic buildings and landscapes, and how they have adapted and evolved over time.

Let’s explore how suburbia came about in England from the 1820s.

How did the suburbs develop in England?

People have lived and worked on the edges of cities and towns for centuries, but the possibility of retreating to the suburbs for a more private and healthier lifestyle was initially restricted to the wealthy in the 17th and 18th centuries.

By the 1820s, several of England’s cities and towns had experienced enormous growth, particularly around ports, spas, resorts, and manufacturing centres. Consequently, more residential areas needed to be developed on the margins of urban areas to house the growing population.

As more people became eligible to move to the suburbs, different development models, planning approaches, and design trends emerged.

Since its first appearance in the early 19th century, the ‘park’ suburb has proved an enduring type. At first, these schemes often favoured picturesque layouts, private roads, and individual houses or semi-detached pairs in private gardens. But they have subsequently become more diverse.

Bedford Park in west London is a much-praised development that was started in 1875 by a cloth merchant, Jonathan Carr. These semi-detached houses on Woodstock Road were derived from a design by architect Richard Norman Shaw.

Its compact, visually appealing houses and social facilities were aimed at the ‘aesthetic middle-classes’.

Popular conceptions of the ‘suburban’ do not commonly include closely packed terraces of houses, but these ‘non-leafy’ suburbs made up the greater proportion of urban expansion before the First World War.

For the working-classes at this time, there was a key shift away from having multiple families under one roof to living in a single-family terrace house.

The building blocks of suburbia

Building suburbia in England has been the work of many hands. It has involved landowners, developers, financiers, and the building trade acting together, and required the input of architects, surveyors, engineers, estate agents, and planners.

Historically, it was the work of private enterprise, but since the late 19th century, suburban development has also been undertaken by organisations with a philanthropic purpose and by local authorities.

From the mid-19th century, the demand for building land encouraged the formation of specialist providers such as freehold land societies. They purchased land, divided it into building plots and laid out the roads.

One example is the suburb of Freehold in Lancaster, laid out by the town’s second freehold land society in 1852 and built up over several decades.

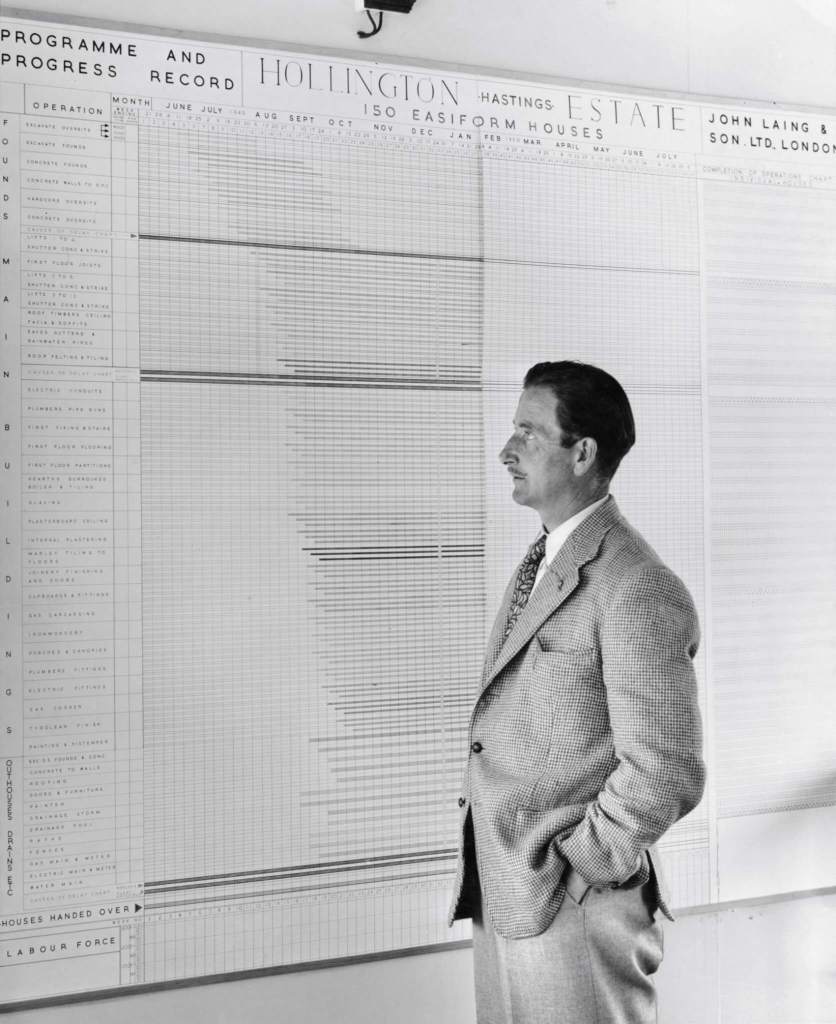

House building in the suburbs was usually undertaken by local firms operating at a modest scale. This began to change in the interwar years (1918 to 1939) with the rise of large-scale businesses such as John Laing.

By the 1930s, Laing had a highly developed management system that could chart all the stages of a project. Their ‘Easiform’ concrete housing system, patented in 1924 and revised in 1943, was used widely in the post-war housing programme, including the Hollington Estate in Hastings, East Sussex.

Controlling suburban development

Before the era of modern planning controls, a particular suburb could be carefully built up and skillfully maintained through estate management. But this was never the case with the majority of suburban growth.

Since the mid-19th century, there has been a gradual rise in state intervention, and measures have been introduced to influence suburban development, from building byelaws to statutory town planning and a national planning system.

One planning approach that emerged during the 19th century was residential zoning. The suburb of Clifftown in Southend on Sea was laid out between 1859 and 1861 for Sir Morton Peto, E.L. Betts and Thomas Brassey, and constructed by the builders, the Lucas Brothers.

5 classes of terrace houses were constructed. The lowest value properties adjoined the railway line, while the most expensive faced onto a seafront garden square.

After a period of post-war experimentation in planning and design, suburban residential schemes began to favour historically styled exteriors with modern interiors and building services.

One influence has been the Essex Design Guide, published in 1973. An early example of its approach was Noak Bridge, Basildon, which began in 1979.

Designing the suburbs

Even a cursory tour of England’s suburbs reveals a rich diversity of approaches and landscapes. These have sometimes drawn on picturesque notions, but formal and rectilinear planning (a grid street plan) has been another influence.

The design of suburbs has often been conceived as a compromise between town and county. Perhaps the most influential interpretation of this idea has been the garden suburb, a variant of Ebenezer Howard’s social and economic vision of the garden city.

As expressed through the planning ideas of Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker, this produced an orthodoxy of housing groups in short terraces or pairs, laid out in cul-de-sacs or around greens and combined with other facilities in a unified landscape.

These planning principles were used for the Well Hall Estate in Greenwich, London. Designed by a team under Frank Baines at the Office of Works for the Ministry of Munitions and built mainly during 1915, the estate, which was a short tram ride away from Woolwich Arsenal, provided houses and flats.

In the post-war period, government advice advocated the planning of new suburban areas as integrated ‘neighbourhood units’.

An early and influential example is Mark Hall North in Harlow, Essex, the first of 4 neighbourhoods to be started in Harlow New Town, designed in 1949 by Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew.

What style of buildings are popular in the suburbs?

Residential buildings dominate the makeup of most suburbs. The detached house, the terrace and the flat have evolved their own suburban versions. However, the semi-detached house and the bungalow perhaps represent the archetypal suburban dwelling types.

The semi-detached house has taken various forms. One design has been to disguise the pair as a single building, allowing for a grander impression. This approach was used by John Claudius Loudon when he designed a ‘double detached villa’ partly for his own occupation at 3 to 5 Porchester Terrace, Bayswater, London, in 1825.

Suburbs also contain a range of other building types serving their local communities. These include shops, workplaces, leisure facilities and places of worship.

In the late 20th century, mosques became common additions to inner suburban locations, serving communities that arrived from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and other Muslim-majority countries.

However, the building type has a longer history in England. The first purpose-built example, the Shah Jahan Mosque, was opened in 1889 in Woking and was designed by William Isaac Chambers.

Suburban landscapes and recreation use

Until the mid-20th century, the edge of a city or town was often a rapidly moving frontier. This meant extending into surrounding areas that had long been shaped by the needs of the urban populations, supplying many of their daily necessities and accommodating a range of functions and activities.

One of the long-established land uses for the urban margins is recreation. These spaces have often proved vulnerable to redevelopment, but the move towards garden suburb layouts allowed sports facilities to be accommodated within the residential blocks.

This was the case at Burnage Garden Village, a development of 136 houses by Manchester Tenants Ltd that began in 1908 and was built by the local co-operative society.

The housing is laid out around a bowling green and tennis courts with a clubhouse-come-village hall.

For many, private outdoor space is at the heart of the suburban dream. The reality can be modest in extent, but in the 19th century, the garden of a high-status suburban villa could be extensive.

According to a sales brochure from 1864, a garden at Keithfield contained a drive, lawns, flower beds, a kitchen garden, cold frames and a greenhouse.

Change in the suburbs

Change happens constantly in the suburbs. Areas can undergo gentrification and revival or experience decline and redevelopment, while modernisation and ‘home improvements’ can subtly transform their character.

When the housebuilders Costain began their ‘garden city’ at Elm Park in Havering, London, in 1933, it was marketed at working-class people who wanted to enjoy a suburban life.

Different classes of houses were provided, with the cheapest being terraces of identical dwellings.

Kimmel Street in Toxteth, Liverpool, is one of the ‘Welsh Streets’, a ladder of terraces built in the 1870s and selected for redevelopment in the 2000s.

Following a campaign by heritage organisations and local community groups and a public enquiry, the houses were refurbished in 2020 after years of dereliction.

Today, most people in England live in outer urban or semi-rural areas, where they have access to shopping and leisure and are commutable places for work in urban centres.

The appeal of a suburban life may have emerged centuries ago, but it continues to endure.

Written by Joanna Smith and Matthew Whitfield

Discover your historic local heritage

Hidden local histories are all around us. Find a place near you on the Local Heritage Hub.

Further reading

Leave a Reply