King Henry VIII is one of the most infamous monarchs in English history. Historic sites like Hampton Court Palace and Westminster Abbey are often well known backdrops to his 36 year reign.

Being the second oldest son of King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, Henry wasn’t meant to inherit the throne. But when his older brother, Prince Arthur, died at age 15, he became heir to the throne and later King of England in 1509.

Like him or loathe him, his dramatic religious reform shaped Britain as we know it, and his 6 wives – each with their own legacies and stories – still fascinate people today.

Here are some lesser known places across England that help tell the story of Henry VIII’s reign.

1. Eltham Palace, Greenwich

Henry VIII was born at Greenwich Palace on 28 June 1491, but he spent much of his childhood nearby at Eltham Palace. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, it was a significant royal palace favoured by visiting monarchs who enjoyed the extensive hunting grounds. But primarily, it was used as a nursery for Henry VII’s children.

Henry was the last monarch to invest substantially in Eltham when he added new royal lodgings there.

The Great Hall was constructed in the 1470s for Edward IV and still exists today.

After over 300 years as one of England’s most prominent royal households, Eltham fell into decline and was overshadowed by Greenwich Palace and Hampton Court Palace.

2. Whitehall Palace, London

Originally built for archbishops, Whitehall Palace, once known as York Place, became one of Europe’s largest palaces during Henry VIII’s reign.

After Cardinal Wolsey failed to annul his marriage to Katherine of Aragon, Henry seized the palace and renamed it ‘White Hall’ in 1532.

It was here that he married Anne Boleyn in 1533 and Jane Seymour in 1536.

The Tudor Whitehall Palace was destroyed by fire in 1698, but parts were uncovered during the Ministry of Defence’s construction, which was built on the site in the mid-20th century.

Plans to destroy this discovered Tudor wine cellar were halted thanks to Queen Mary, widow of King George V. The cellar is now preserved in the newer building’s basement.

Henry VIII died at Whitehall Palace on 28 January 1547, aged 55.

3. Buckden Towers, Cambridgeshire

Henry sent his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, to Buckden Palace, as it was formerly known, after their marriage was annulled in 1533.

Katherine was popular with the villagers, so Henry sought to move her elsewhere. He sent Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, to move Katherine to a different property away from her supporters, but she resisted.

She eventually moved the following year, but Buckden became a place where Henry’s long-standing first wife remained firm against him and his orders.

Henry also visited here years later with his fifth wife, Catherine Howard, in 1541.

4. Acton Court, Gloucestershire

Acton Court is often known as one of England’s best preserved Tudor manor houses.

Royal Progresses helped the monarchs vacate the city in the summer months and connect with people across their kingdom. Monarchs stayed with their close royal courtiers, and it was common for owners to renovate their houses extensively to ensure they were fit for royalty.

In 1535, the owner of Acton Court, Nicholas Poyntz, built an entirely new East Wing in honour of Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn, during their summer progress around the West Country.

Poyntz went to immense trouble and expense, decorating the state apartments lavishly and fashionably. His effort seemed worth it, as he was supposedly knighted during the couple’s visit.

Much of the 16th-century historic fabric survives, including stone doorways, panelling, fireplaces and even decorative friezes that Henry and Anne would have seen.

5. Rievaulx Abbey, North Yorkshire

The dissolution of the monasteries was one of Henry’s most important political legacies, significantly impacting today’s historic environment.

Hundreds of monasteries, abbeys and other religious houses were dissolved between 1536 and 1541, and Rievaulx Abbey was no exception.

Suppression Acts were passed in 1535 and 1539, resulting in the devastating loss of properties, land and wealth, which were either transferred to the crown or sold off to supporters of the King.

Rievaulx Abbey was founded in the 12th century and was once one of the foremost Cistercian monasteries in England. The abbey was closed in 1538 and sold to the Earl of Rutland.

Around 800 monasteries were dissolved or closed across England. Monastic ruins throughout the country and are a stark reminder of Henry’s role in the Reformation.

6. St James’ Church, Louth, Lincolnshire

Henry’s decision to break from the Catholic Church and become the Supreme Head of the Church of England did not come without opposition. Henry and Thomas Cromwell‘s policies resulted in the largest rebellion in Tudor history.

The Pilgrimage of Grace, as it is more commonly known, was a series of rebellions that took place in the North of England between October 1536 and January 1537.

The Lincolnshire Rising was one of the first, and it all started in St James’ Church in Louth, where protestors first gathered. Rebels seized hold of the church to ensure nothing was stolen or taken by the crown.

Henry responded by sending the Duke of Suffolk with an army of thousands to put down the rising. Most of the protesters dispersed before any violent action took place. However, a number of the ring leaders were arrested and executed.

The Lincolnshire Rising was a brief but direct protest against the dissolution and marked the start of religious unrest, which became a real threat to Henry’s reign.

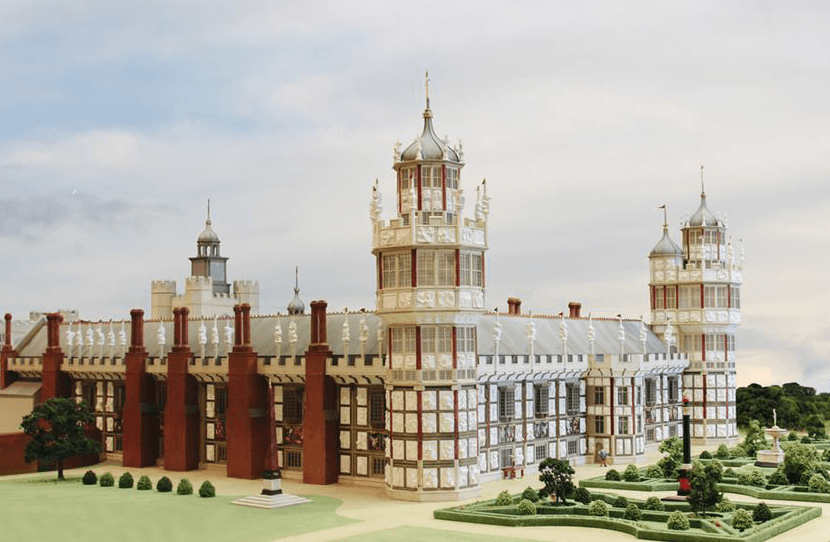

7. Nonsuch Palace, Surrey

Nonsuch Palace was one of the largest of Henry’s building projects during his reign. It was ambitious in style and size and named ‘Nonsuch’ because there would be no such palace like it.

It was commissioned in 1538 to mark the birth of Henry and Jane’s son, the future King Edward VI.

Construction began in 1538, but Henry died before it was completed. It was eventually demolished in 1682 by Charles II’s mistress, Barbara Villiers, to help pay her debts.

8. Calshot Castle, Hampshire

Calshot Castle was part of the extensive network of coastal defences built under Henry’s orders. These artillery castles and forts were built at a time of great political turbulence after England’s break from the Roman Catholic Church.

This artillery fort was completed in 1540 to help defend England against potential attacks from France and the Holy Roman Empire. Calshot guarded the entrance to Southampton Water against the threat of invasion and was part of Henry’s major maritime defence programme.

These forts protected some of the most important stretches of coastline, such as the Downs in Kent, Falmouth Harbour, the Thames Estuary, and the Solent in Southampton.

By the end of the 1540s, Calshot was one of the most heavily armed of the Solent fortresses, with a total of 36 guns.

9. King’s Manor, York, North Yorkshire

When Henry and Catherine Howard visited King’s Manor in 1541, the memory of the Pilgrimage of Grace was still fresh in people’s minds.

Today, the building backs onto the ruins of St Mary’s Abbey, yet another monastery lost under Henry’s orders and where Henry and Catherine stayed during their 12-day trip. It was originally constructed in 1270 as an Abbot’s house.

The heavy resistance and rebellions in the north prompted Henry to revive the Council of the North, an administrative body designed to enforce crown policies in the region.

The surviving Abbot’s house in York was used as the council’s headquarters in 1541.

York was the furthest north Henry had ever travelled.

Extensive building work was undertaken in preparation for Henry and Catherine’s arrival, and it was this visit that gave the building its current name, King’s Manor.

The Council of the North continued here for 100 years until it was disbanded in 1641.

10. Windsor Castle, Berkshire

Henry VIII died at Whitehall in 1547, and his 9-year-old son, Edward VI, subsequently became King of England. Historians are not certain about how Henry died, but his obesity may have contributed to possible organ failure, as well as an ulcerated leg wound from a jousting accident.

While it is often thought that he is buried in Westminster Abbey, Henry VIII is buried in a vault in George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle alongside his third wife, Jane Seymour.

Henry, who took great pride in his public image and how he was viewed, had detailed plans for an elaborate tomb. However, his requests were never followed through, and his body remains in a tomb now marked by a fairly understated marble slab in the altar.

Despite his lifelong hopes of securing a male heir, the succession did not unfold as Henry might have hoped.

His son, Edward, died in 1553, aged 15. His eldest daughter, Mary, then inherited the throne, becoming the first Queen Regnant of England. She reigned for 5 years, dying in 1558, aged 42.

But it was Elizabeth, his daughter by Anne Boleyn, who ultimately reigned supreme. Elizabeth I became the longest-reigning Tudor monarch, ruling for 45 years. Her decision never to marry or have children marked the end of the Tudor dynasty when she died in 1603.

Discover your historic local heritage

Hidden local histories are all around us. Find a place near you on the Local Heritage Hub.

Further reading

Leave a Reply