Following Emperor Claudius’ conquest, the Roman Empire lasted from AD 43 to AD 410 in Britain. After more than 3 centuries of direct rule, Britain stopped being of the empire, when local rebellions and an emperor with more pressing concerns closer to home made central rule untenable.

We have previously explored the basis for the Arthurian legend, which has its source in the events of the 5th and 6th centuries AD.

Here, we look at what the archaeological evidence can tell us about life at that time after the Romans left England’s shores. This period is like a long journey where the scenery changes dramatically between the starting point and the destination.

In the beginning, we have a Roman province (however troubled) with its towns, villas and defensive structures.

At the end, we have an array of small kingdoms of people identifying with rich cultures, either inspired by Germanic people from the North Sea area or evolving British (or Welsh) identities, all mostly without cities as we would recognise them.

But how did this massive change happen?

When and how did Roman rule end in Britain?

As recorded by the eastern Roman Zosimus, the basic narrative is that direct Roman rule ceased in AD 410. We hear from Zosimus that the emperor of the western half of the empire, Honorius, told Britain’s cities to look after their own defence (he had his hands full with the Goths in Italy).

Also, Britain previously had broken away under rebel emperors at various points, most recently in AD 407 when a Roman soldier from the field army rebelled and set himself up as ‘Emperor’ Constantine III, probably as a result of mutiny over the troops’ pay arrears.

He was killed after campaigning against the official emperor’s forces in Gaul (present-day France). It’s likely that he took some of the field army with him and they didn’t return.

What do the written sources tell us about this time?

Contemporary or near-contemporary written sources for the immediate period after AD 410 are very scant. As noted in our Arthurian legends blog, the key source from the time is the narrative written in Latin by the British monk Gildas.

His story describes the decay of the Roman province, raids by barbarians (Picts, Irish and Saxons), the rise of a “great Tyrant” and the rebellion of Saxon mercenaries, Britons being driven into the west of the island and the squabbling of British petty kings to his day.

He records that there seems to have been a last-ditch appeal by a pro-Roman faction to get aid from Aetius, the warlord-governor of what was left of Roman Gaul in the mid-5th century.

However, some scholars think he may mean the appeal was to Aegidius, a slightly later ruler of a sub-Roman rump state around Soissons. In either case, it appears that the plea was not answered.

Gildas’ narrative reads more like a sermon than a history, and he lambasts his compatriots for their moral failings.

While historians have different theories, we are also not conclusively sure exactly when he wrote his account; it could be anywhere between about AD 450 and AD 550. So, we don’t know exactly how close he is to the first decades of post-Roman life.

There are also some records about the life of a saint-bishop Germanus from Gaul, who we are told visited Britain in AD 429 on a mission to stamp out heresy there. He visited the shrine of St Albans. Allegedly, he also helped to defeat a pagan Saxon band by getting the British to shout “Alleluia” at them. The description gives the impression of troubled but still functioning British communities in the south.

There are chronicles compiled many centuries later by the Welsh and Saxons, but these are very distant from the events and try to ‘retrofit’ competing traditions in their own day. Both tell a story of mutual violence.

What does archaeology tell us about the period after Roman rule?

After the end of the Roman Empire in England, the inhabitants of the former province might have experienced the changing circumstances differently depending on their class or degree of Romanisation.

Urban decay after the Romans

Roman towns had generally been in some difficulty before AD 410, with evidence of a decline in the use of many places and economic troubles. However, some places, such as Cirencester in the west, flourished for much of the 4th century.

After the end of direct Roman rule, urban life fell apart in the space of a couple of generations. With no standing army or groups of officials as customers and no steady flow of central coinage as pay for those groups, urban economies collapsed.

Even in once prosperous Cirencester, the forum (or marketplace) went out of use, and its paving was covered by silt. Some inhabitants relocated to shacks within the town’s amphitheatre, perhaps as a more defensible site.

The need for defence also saw the reoccupation of several ancient hillfort sites, such as Cadbury Castle in Somerset.

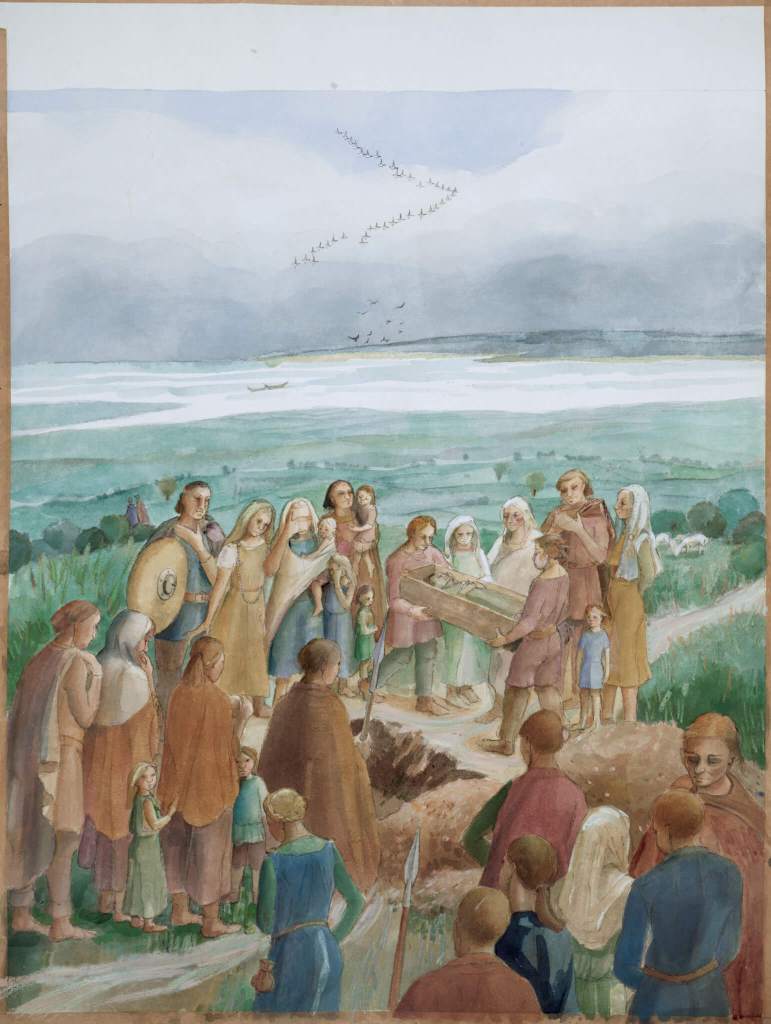

In several towns, there is evidence of un-Roman burial habits, such as inside settlements, including within decaying buildings or ditches.

At Wroxeter, in Shropshire, there is some evidence of a revival of settlement in a part of the town: a complex of new wooden buildings in the area of the old Roman baths basilica. Quite how urban this development was is still being debated. Some historians and archaeologists see this as evidence of the ‘privatisation’ of towns by local strongmen.

The countryside after Roman rule

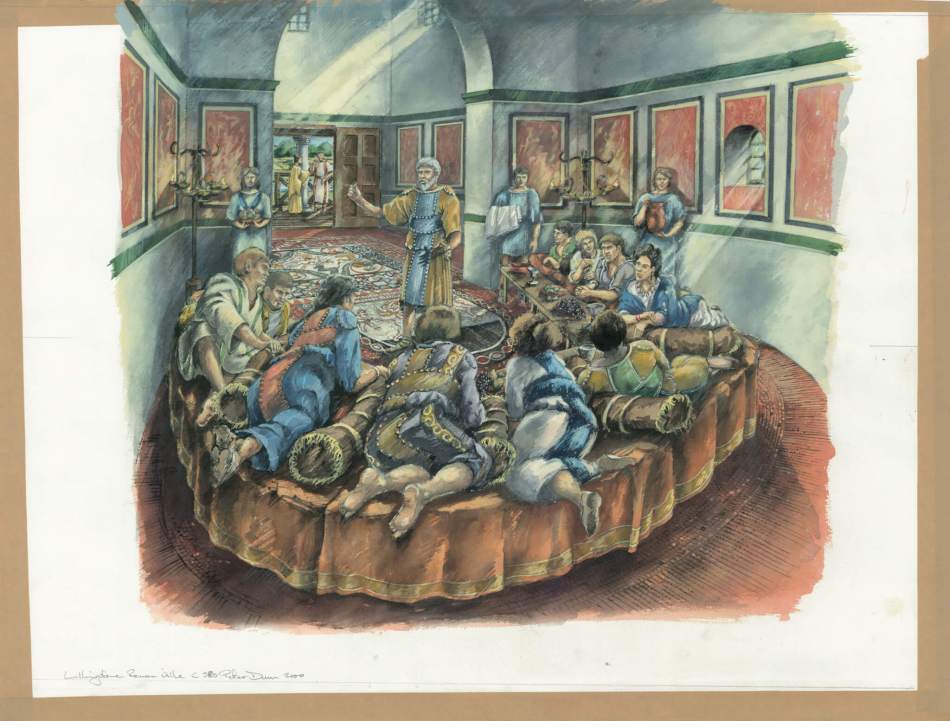

In the countryside, especially in the west of England, the century before the end of Roman rule had continued to be good to wealthy landowners, who built or extended large villas with impressive mosaics.

After direct Roman rule ended, the villas generally seemed to have suffered a decline in their fortunes and were eventually abandoned. There is evidence of a change of function in some previously elaborate rooms, such as occupants keeping livestock in them or digging corn-drying ovens through mosaic floors.

However, at Chedworth Roman Villa in Gloucestershire, there is evidence that bucks this trend. New dating has shown that after AD 424, a new mosaic was laid. It is not as elaborate or technically skilled as some previous ones at the site.

However, it is significant that it happened at all, and that the owner could devote resources to having a new mosaic floor laid and find the craftspeople to carry it out.

The evidence for the ordinary country people in this period is much more fleeting. They may have even welcomed lower taxes and less control by the local landowners and the Roman state, though this has to be balanced against the dangers of the more unstable times.

Gone to pot?

Continuing the crafts theme, as the army, administration and urbanised elite customers faded away, Britain’s Roman wheel-thrown pottery industry quickly ceased making new ceramics.

Existing wheel-thrown pottery was apparently used until it finally broke, to be replaced by hand-thrown coarse pottery (which is hard to date by archaeologists) or perhaps wooden vessels which haven’t survived. As we will see, some high-end customers satisfied their need for display by importing pottery from abroad.

What happened to the army after the end of the Roman empire?

We have already mentioned the army, but what happened to them? Some of the small force of elite mobile field army units may have already left.

However, Hadrian’s Wall was garrisoned in the late Roman period by static border troops known in the Roman records as ‘limitani’, who were there to control northern raiders like the Picts.

Unlike the elite mobile field army, many of these troops, with their local loyalties, didn’t leave after direct Roman rule ended. Indeed, there is evidence that several forts were occupied for centuries after.

The nature of the occupation changed. An example of this is at Birdoswald, where large wooden halls were built. Some archaeologists and historians have suggested that these could be the feasting halls of the descendants of the Roman soldiers and their commanders, who were no longer paid by the Roman administration and had to look after themselves and their families, mutating into small warbands.

They may have had to compete with other neighbouring garrisons turned warbands as well as northern raiders.

Did any areas flourish after the end of Roman rule?

Archaeology shows us that it wasn’t all doom and gloom. In some places, far-flung trading connections continued.

An example is at Tintagel in Cornwall, then part of the kingdom of Dumnonia. The famous medieval castle was built much later, and its construction was influenced by tales linking the place to Arthurian legend.

However, archaeologists have uncovered several 5th to 7th-century post-Roman buildings with stone footings.

They also found large quantities of imported high-status pottery (especially wine jars) from the Mediterranean, specifically North Africa and Asia Minor, along with imported glass vessels.

We can’t be sure what the people of Tintagel were trading in return, but tin is a strong possibility.

Also, in Cornwall, there are a number of incised memorial stones with British or Roman-sounding names or Christian symbols, such as “Cumregnus son of Maucus” commemorated on a stone at St Sampson’s Church in South Hill.

The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in England

In addition to the culture of the Britons, archaeology has revealed a great deal about the new Anglo-Saxon culture spreading from the east coast (see more in ‘Five Sites That Tell the Story of Early Anglo-Saxon England’).

Following the collapse of Roman rule, a mix of people from northern Germany and Denmark travelled to Britain. The resulting culture eventually became dominant in England until the Norman Conquest in 1066.

There has been much debate about the extent of migration from Germany and neighbouring coastlands and whether incomers displaced the local populations. It is fair to say that the picture is certainly more nuanced than the view of ‘ethnic cleansing’ given in Gildas’ sermon.

However, some current interpretations are moving back to the idea of there being considerable real migration.

Investigations of human remains using DNA or isotope analysis on teeth may shed more light on this, but are only just beginning. The Isotope technique shows where a person may have grown up.

Evidence from some Anglo-Saxon cemeteries in eastern England shows a high percentage of people coming from the Saxon homelands. Some investigated in the south-east show DNA linked to western Germany, France and Belgium- possibly Frankish.

In other places, there may have been more of a gradual mingling of populations with the local people throwing in their lot with the successful incomers’ way of life, using their metalwork styles, perhaps taking on their religious beliefs over time.

In some places, there is a continuity in land use patterns, so perhaps in some cases just the landowners changed to begin with. In some areas, Anglo-Saxon settlements are on marginal land that would not have been such a great loss to the locals.

There is no direct archaeological evidence for wholesale massacre, but doubtless, there would have been conflict between different groups.

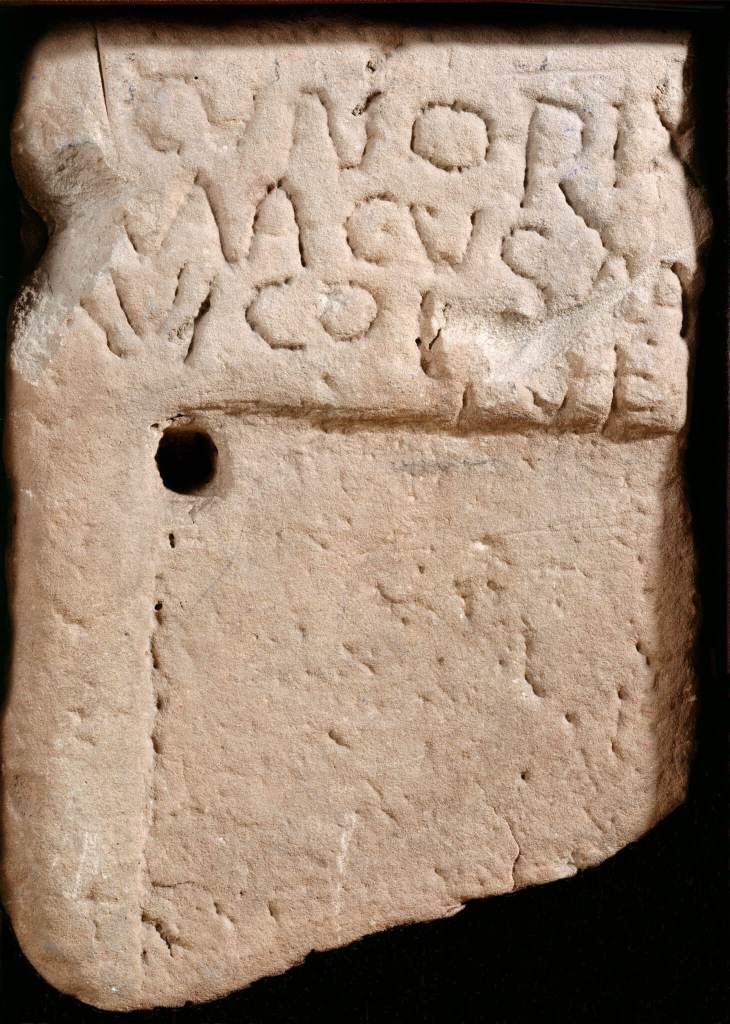

There were also people coming from Ireland during this period. At Wroxeter, there is a tombstone in Latin letters with an inscription recording Irish names: “Cunorix macus Ma-q̣ui Coḷiṇe”, so probably “Cunorix the son of Colini”.

“Cunorix” means ‘Hound-King’. He may have made himself a local ruler or have been a mercenary.

Cultural differences hardened later as the various bigger kingdoms making up ‘England’ and ‘Wales’ began to emerge from the post-Roman period of instability.

We can see this in early law codes of Wessex, where compensation for crimes such as murder (weregeld) depended on whether one was ‘Welsh’ or ‘Saxon.’ Cornwall and Cumbria would long have their own separate identities.

The end of an era and a new beginning

So archaeology gives us a complex, varied and subtle picture of definite change over the 5th and 6th centuries and also opens up vistas of the fascinating new era of Anglo-Saxon England.

Further reading

Leave a Reply