What does the name ‘King Arthur’ bring to mind for you?

Chivalric tales of knights of the Round Table and their ladies? Maybe a Romano-British general beating off Saxon invaders from the continent? Or perhaps a ‘Celtic’ resistance leader?

The story of King Arthur has fascinated people for hundreds of years, particularly after medieval versions of the legends were brought together in ‘The Matter of Britain’, an attractive fantasy world for the medieval elite, much later repackaged in numerous books and films.

Was King Arthur a real person?

Before looking at the places associated with the Arthurian legends, you might wonder if there really was a historical Arthur.

There is little conclusive proof in historical sources or archaeology for a ‘King Arthur’. So, what can we say about evidence for the original ‘Arthur’?

Historians think the source of the stories about Arthur lies in the confusing events of the 5th and 6th centuries AD after Roman rule collapsed in Britain.

A case of a ‘missing’ Arthur?

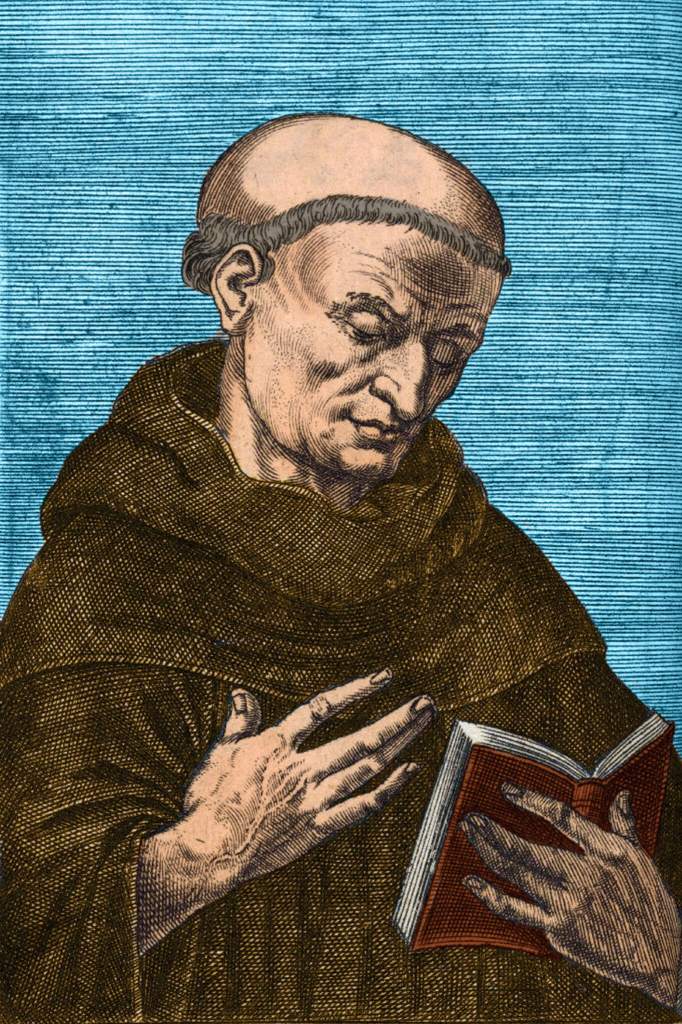

One of the main written sources for the immediate period after 410 AD is ‘The Ruin of and Conquest of Britain’. This is essentially an intense sermon attributed to a British monk, Gildas, directed against the British clergy and rulers of his day.

In it, Gildas paints a picture of the events leading up to his lifetime. He mentions a battle later associated with Arthur and names a number of other rulers, but not Arthur himself.

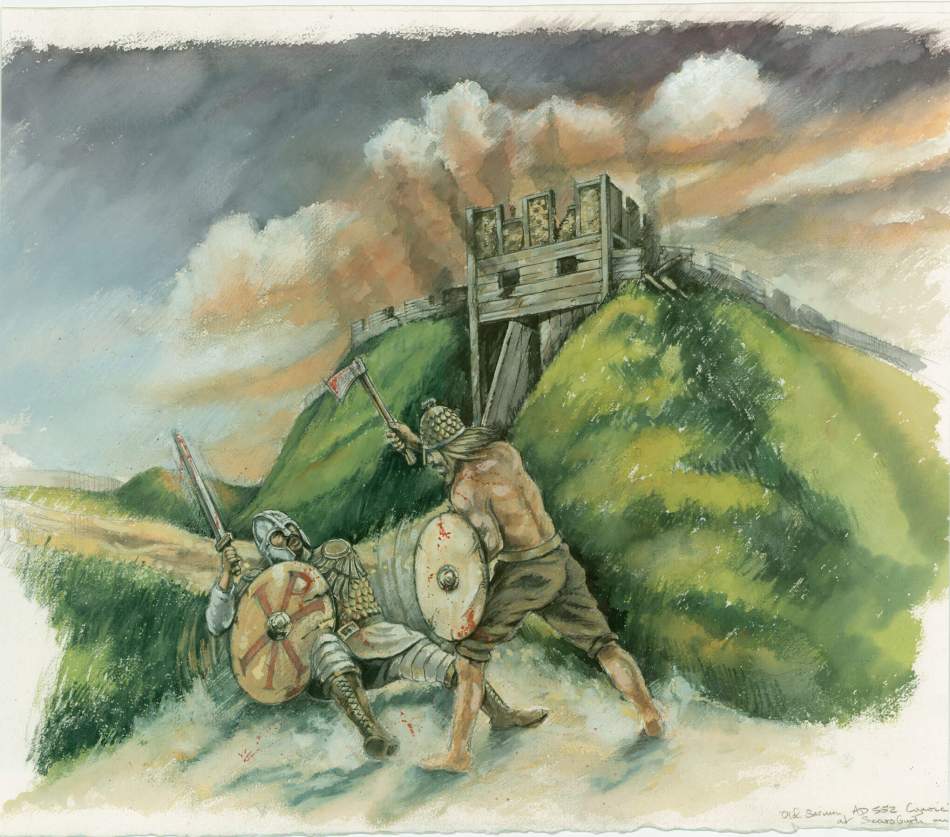

Gildas presents a bleak picture of a hapless tyrant (later associated with the figure of Vortigern) who invited Saxon mercenaries to fight for him against other raiders (the Picts and Scots).

He recounts that the Saxons then rebelled and began to take the land in the east of the country for themselves.

Gildas mentions a fightback led by a Roman-sounding leader, Ambrosius Aurelianus, rather than Arthur, with a battle at Badon Hill.

He seems clear in his mind that this battle really took place because he says it was in the year of his birth. Later medieval writers tried to square this by claiming that Ambrosius was Arthur’s uncle.

Catterick: Arthur’s first mention… if only in passing

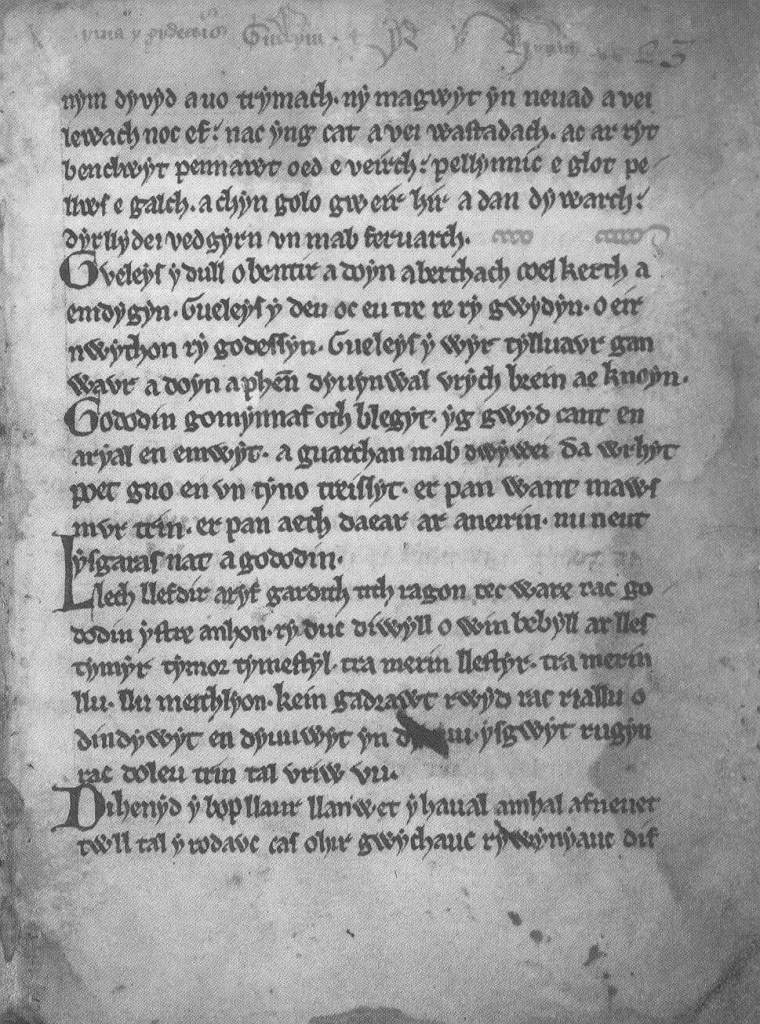

The earliest actual mention of Arthur comes from a Welsh poem, ‘The Gododdin’, about another British fight-back. The Gododdin were the northern British inhabitants of a territory spanning what would later be Northumberland and southern Scotland.

The surviving manuscript is a medieval copy of the poem, but the tale is likely to have been composed from the 6th or 7th century onwards (although some authorities think it is as much as 200 years after that).

He fed black ravens on the rampart of a fortress

Though he was no Arthur

Among the powerful ones in battle

In the front rank, Gwawrddur was a palisade.Extract from Welsh poem ‘The Gododdin’

Curiously, it only mentions Arthur by comparison to one of the heroes attacking the former Roman base at Catterick (Catreath), by then held by the Angles.

So, in song and literature, Arthur was clearly already viewed as someone to aspire to.

Tintagel: the legendary place of Arthur’s conception and birth

By the 12th century, chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that Tintagel in north Cornwall was where Arthur was conceived, and by the 15th century, it was said that he had been born there too.

In the later medieval legend, Uther Pendragon, the High King of Britain, becomes obsessed with Ygraine, the wife of Gorlois, ruler of Cornwall. Merlin, his wizard, disguises Uther to look like Gorlois so he can lie with Ygraine at Tintagel.

The circle of Arthurian legends influenced how the real medieval castle at Tintagel was built as a place of chivalric display.

Tintagel was also an important trading site in post-Roman Britain, which saw the genesis of tales about Arthur.

Where is Camelot supposed to be?

In the later medieval legends, Camelot is the location of Arthur’s court and home of the ’round table’ of knights.

Later medieval writers thought this might be at Caerleon in Wales or Winchester in Hampshire. In Winchester’s Great Hall, you can see a later medieval ’round table’ created as part of that era’s fascination with the Arthurian legends.

Based on a reference by the Tudor writer Leland, others have speculated that it might have been at the hillfort of Cadbury Castle in Somerset.

Excavations at this mainly prehistoric site have revealed that it does have evidence of post-Roman re-occupation.

Arthur: war leader

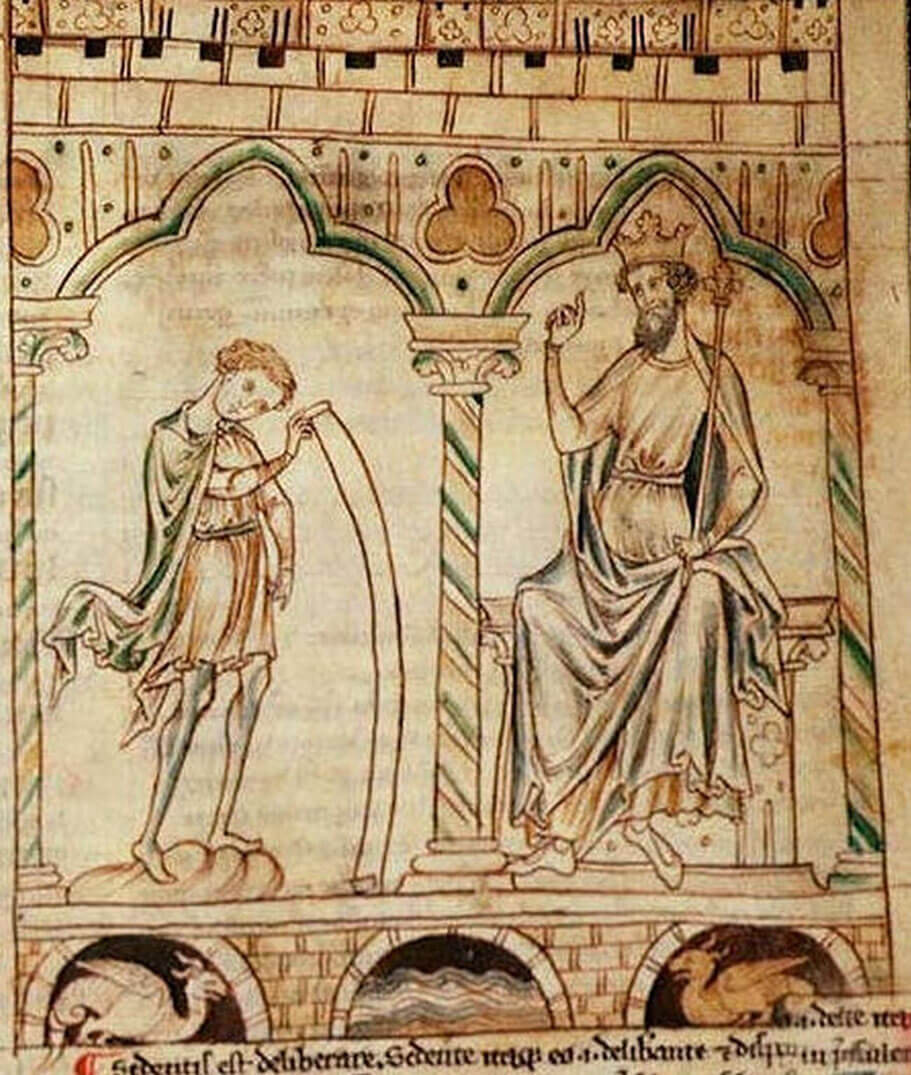

The 9th century British historian Nennius refers to Arthur not as a king but by a pseudo-roman military title of ‘Dux Bellorum’, meaning war leader. Towards the end of the Roman empire in the west, a ‘Dux’ had been a leader of a specific military area.

Nennius lists Arthur’s 12 main alleged battles. Bards, poets, and chroniclers may have retrospectively attributed some of these battles to the hero known as Arthur when they might have had different protagonists. Some may have been selected so they have a poetic rhyme to the names.

The lucky number 12 (the number of Christ’s Apostles) may also be symbolic, with Arthur supposedly perishing in unlucky battle number 13 at Camlann, mentioned in a later source.

The description of Badon Hill is particularly poetic, portraying Arthur as a super-human warrior:

The 12th battle was on Badon Hill and in it 960 fell in one day, from a single charge of Arthur’s, and no one laid them low save he alone.

Later, probably in the mid-10th century, the ‘Annals of Wales’ (or ‘Annales Cambriae’) elaborates on 2 of Arthur’s battles. This ventures to give dates for events: Badon (516 AD), and the additional battle not mentioned by Nennius, Camlann (537 AD), “in which Arthur and Medraut fell.”

Like Gildas’s sermon, the ‘Annals’ and the ‘History of the Britons’ (or ‘Historia Brittonum’) are not necessarily a neutral recording of history. Particularly where Arthur is concerned, they make him a figure of hope and construct a narrative about how the Britons defended themselves.

Where was the Battle of Badon Hill?

The location for Badon has been suggested as being either at Bath; Ringsbury Camp, Braydon, Wiltshire; Badbury Rings, Dorset or Liddington Castle on the hill above Badbury (Old English: Baddan byrig), near Swindon.

How did King Arthur die?

The Battle of Camlann is seen as the final battle King Arthur fought, where he was fatally wounded or died during the conflict.

The search for the location of ‘The Strife of Camlann’ is complex. Some have made an association between Camlann and Camelot.

Perhaps the lead candidate, however, is the Roman fort of Camboglanna or Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall (not Birdoswald as previously thought).

The Isle of Avalon

The area around Glastonbury Tor in Somerset was once marshy, and some have speculated that it became linked to the legendary ‘Avalon’, the island where Arthur is said to have been sent to recover from his wounds in his last battle.

Geoffrey of Monmouth makes the first reference to Arthur’s sword, Excalibur (Caliburn), being forged here.

Glastonbury: the legendary burial place of King Arthur

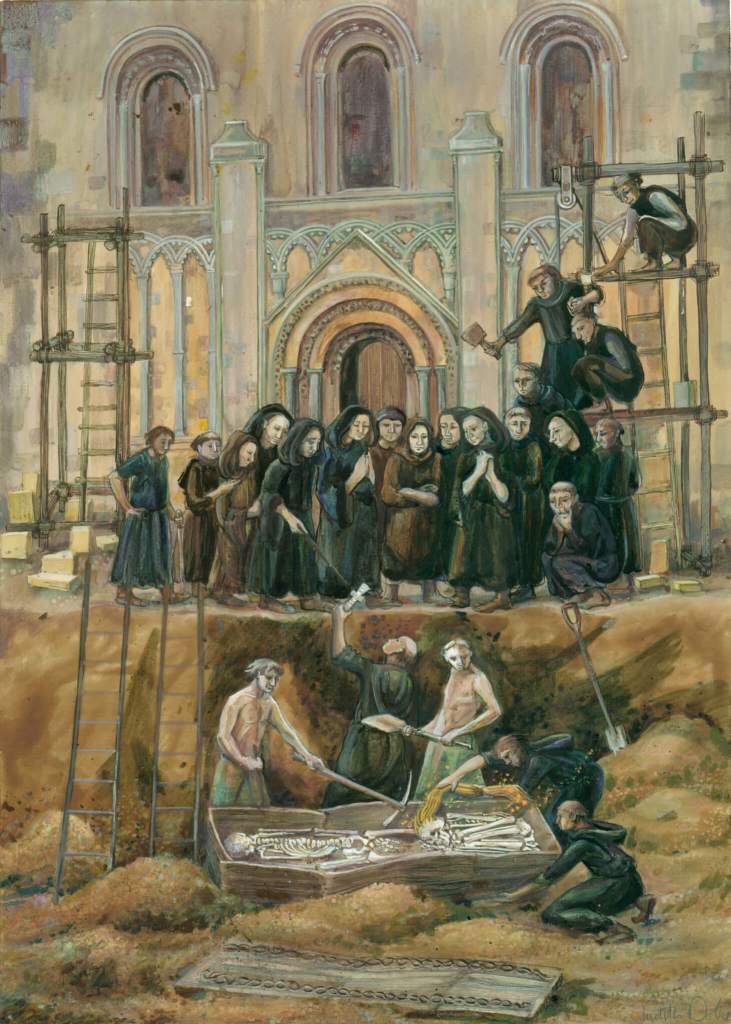

In the late 12th century, the monks of Glastonbury Abbey claimed to have discovered the graves of Arthur and his queen, Guinevere.

However, the timing of this “discovery” is suspect, following as it did after a disastrous fire, which meant the monks needed funds from well-off visitors and pilgrims to rebuild. The wealthy nobles in medieval England loved the Arthurian tales, too.

It seems that both King Henry II and Edward I endorsed the search for Arthur and the discovery, hoping to be associated with the chivalric glamour of the legends.

Beyond the legends: the real ‘Age of Arthur’?

If this article has piqued your interest, look out for a follow-up unpacking what history and archaeology can tell us about what might have really happened after the end of Roman rule in Britain…

Further reading

Leave a Reply