This special issue on Nordic transimperial careers and experiences investigates Nordic people operating in the world of empires ranging from Southeast Asia to Africa, and from Europe to the Caribbean and North America.[1] It focuses on border-crossing individuals, addressing inter-imperial questions of race, otherness, and the civilizing mission, and tying into existing networks, while seeking…

OLd Hist

Book Spotlight “Nationaliser le panafricanisme. La décolonisation au Sénégal, en Haute-Volta et au Ghana (1945-1962) [Nationalising Pan-Africanism: Decolonisation in Senegal, Upper Volta and Ghana (1945-1962)], Paris 2023”

At the end of the Second World War, a new international order was to be defined, requiring reconfigurations in and around colonial societies. Empires becoming obsolete as a form of power were to be dismantled and colonial societies were longing for a fundamental change. As the socio-political order was being redefined, how was the new…

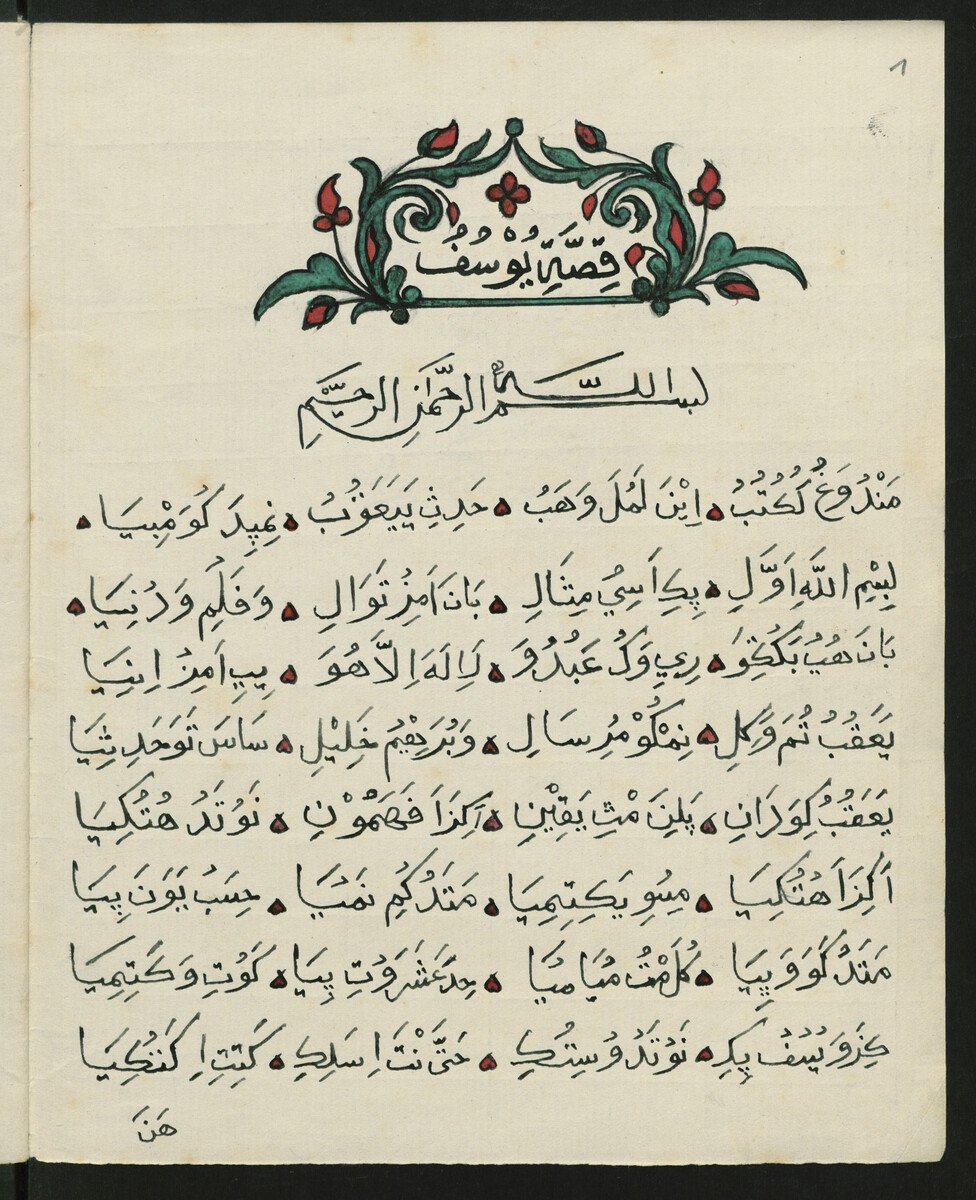

Ein Wettlauf um Swahili-Manuskripte im Kenia der 1930er Jahre: Plädoyer für einen transimperialen Blick auf die Afrikalinguistik

I. Wissenschaftsgeschichte transimperial In den letzten Jahren wurde vermehrt eingefordert, Wissenschaftsgeschichte aus transimperialer Perspektive zu untersuchen. National-imperiale Container müssten aufgebrochen werden, denn sie verdeckten oft mehr Entwicklungen als sie erklärten. Somit reiche die klassische Forderung Ann Laura Stolers und Frederick Coopers, Kolonie und Metropole in einem analytischen Raum zu betrachten,[1] nicht mehr aus. Sie sei…

Cosmopolitan Anticolonialism: The Transimperial Networks of the Hindusthan Association of Central Europe in Weimar Era Berlin

In Weimar era Berlin, Indian students and anticolonialists networked with other exiled communities from subject and colonial nations through the Hindusthan Association of Central Europe (HACE), officially known in German as the Verein der Inder in Zentraleuropa, forging a form of cosmopolitan anticolonialism.[1] Already during the First World War, Germany had attracted anticolonial revolutionaries from…

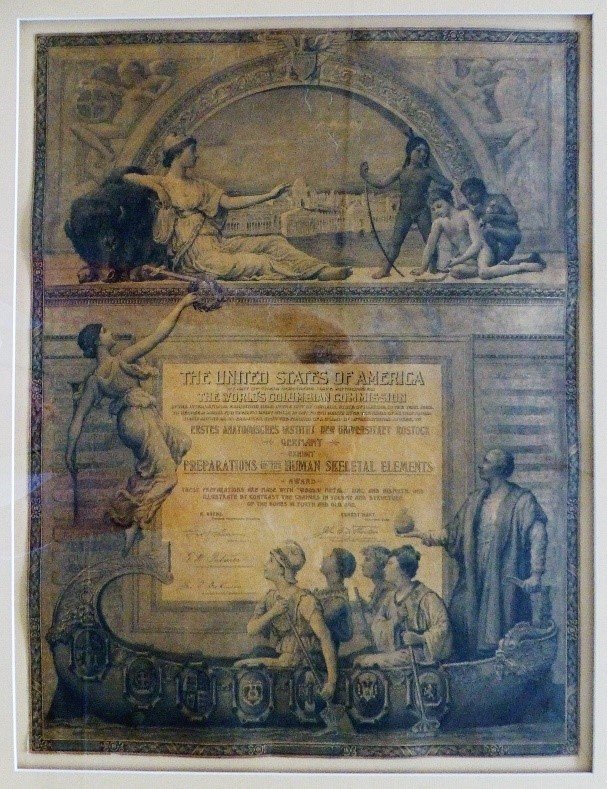

World Expositions as Transimperial Nodal Points and/or Dead Ends: Bogdanov in Paris (1878) and Rostock´s Anatomy in Chicago (1893)

Introduction In 1893, the Anatomical Institute of the University of Rostock, by the German Baltic Sea Coast, participated in the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and was awarded a bronze medal, as well as a certificate for its exhibition of “preparations of the human skeletal elements”.[1] The certificate has recently been rediscovered in the collection…

The Anti-Imperialism of Economic Nationalism: Transimperial Protectionist Networks in Anticolonial Ireland, India, and China

Beginning around 1870, the protectionist US Empire sparked a global economic nationalist movement that spread like wildfire across the imperial world order. Late-nineteenth-century expansionists within the Republican Party got things started in the 1860s when they enshrined what was then known as the “American System” of protectionism – high protective tariffs coupled with subsidies for…

Book Spotlight “Prisms of Work: Labour, Recruitment and Command in German East Africa, Berlin 2024”

Global Labour History My book examines labour regimes in the colony of German East Africa (GEA) before World War I.[1] It uses three case studies: the construction of the Central Railway (1905–1916), the Otto Plantation in Kilossa (1907–1916), and the paleontological Tendaguru Expedition in the colony’s southern Lindi district (1909–1911). Combining global labour history with…

Colonial Visualities and Their Influences Across Empires from the Late 19th to the 21st Century

Intricately linked to postcolonial realities, this essay delves into the visual-cultural connections between the establishment and challenging of white-centric perspectives, with a special focus on resistance to, as well as (re-)appropriations of, visual coloniality by non-white communities.[1] As I show, these (re-)appropriations were partly ambiguous, and cannot be fully explained by exclusively applying Eurocentric theories…

Human Ancestors Created Tools Continuously for 300,000 Years

Goodness gracious, Friends, do I love the science of tree-ring dating! My dissertation research, which I published in 1997 as Time, Trees, and Prehistory, explored the 15-year-long effort, from 1914 to 1929, in which Andrew Ellicott Douglass, an astronomer at the University of Arizona (UA) here in Tucson, along with his rag-tag team of associated…

Trail Memories

Today’s post kicks off our Trails series, a companion to our year-end fundraising campaign. We’ll have weekly essays from now until the New Year. Thanks for your support! Skylar Begay (Diné, Mandan and Hidatsa), Director, Tribal Collaboration in Outreach & Advocacy https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/SkylarBegay_YE2025.mp3 New! Listen to the full blog here. Read by Skylar Begay. (November 20,…

![Book Spotlight “Nationaliser le panafricanisme. La décolonisation au Sénégal, en Haute-Volta et au Ghana (1945-1962) [Nationalising Pan-Africanism: Decolonisation in Senegal, Upper Volta and Ghana (1945-1962)], Paris 2023”](https://oldupexcise.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/1766425080_Book-Spotlight-Nationaliser-le-panafricanisme-La-decolonisation-au-Senegal-en.jpg)