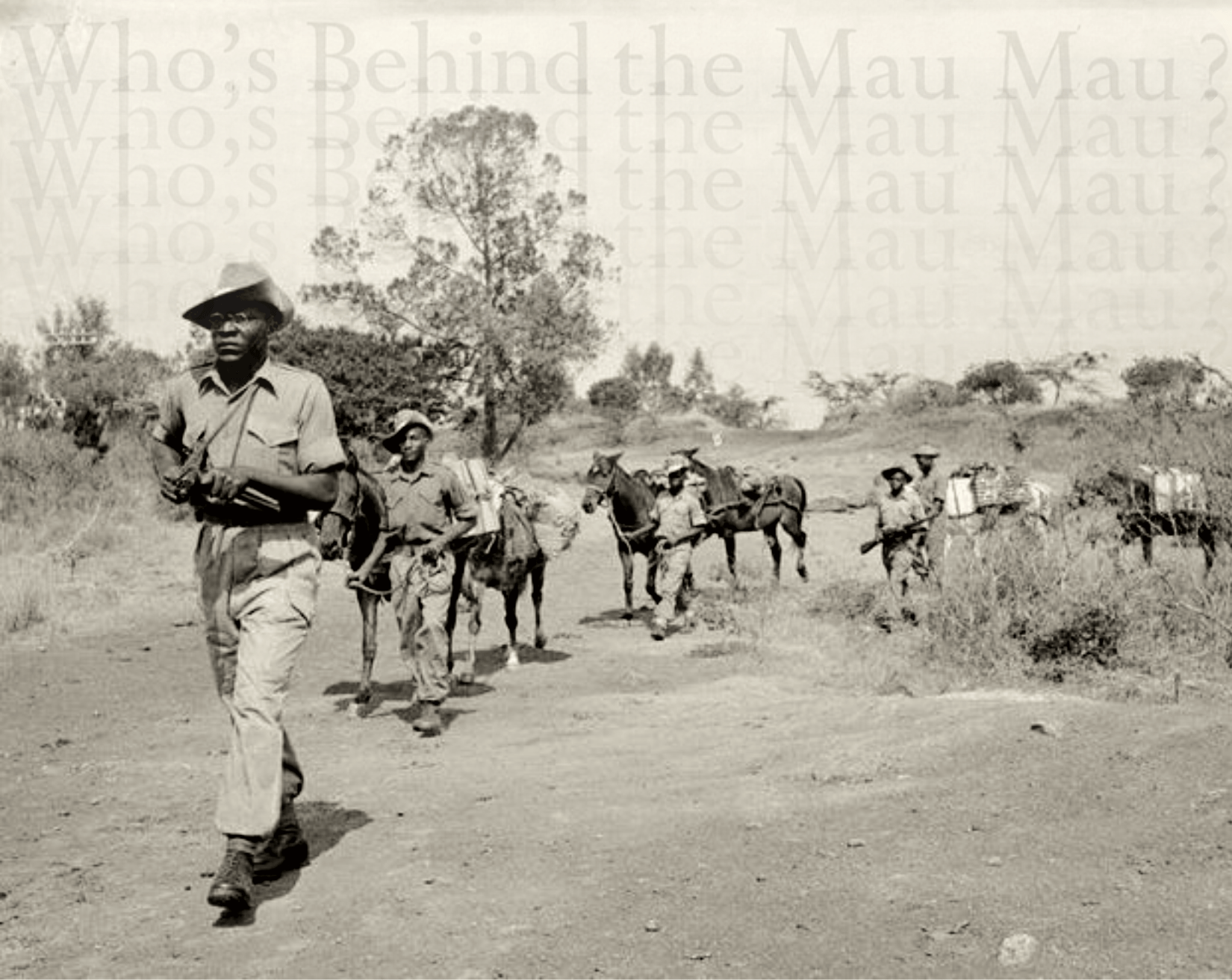

by Christian Alvarado The Mau Mau conspiracy will fail. There is no doubt about that. It started too soon and was on too small a scale. The forces on the side of law and order are being constantly strengthened in numbers and by training. But it is not enough to crush the Mau Mau: How…

OLd Hist

Rediscovering Agricultural Economists for the History of Ideas – JHI Blog

by Federico D’Onofrio In 1920, the agricultural economist and Social-Revolutionary politician, Aleksandr Chayanov published, under the pseudonym Ivan Kremnev, The Journey of My Brother Aleksei into the Land of Peasant Utopia. In this science fiction novella, the protagonist falls asleep in Bolshevik Moscow in 1921, later awakening in the fictionally iconic year of 1984. He…

Latin American Perspectives on Intellectual History and Political Economy – JHI Blog

by David Vertty Though the return of political economy in historical studies is now widely acknowledged, intellectual historians have only begun to assess one of its most promising fields of inquiry: the central role that Latin America has played in building innovative approaches for both of those disciplines. Whether as a point of encounter for…

Mind, Matter, and the Question of Materialist Intellectual History – JHI Blog

by Alec Israeli In the debate between Samuel Moyn and Peter Gordon in Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History on “contextualism” in the history of ideas, there are a few key points of convergence: they each reject notions both of ideas’ absolute transcendence of material conditions and ideas’ absolute debt to material conditions. For both, that…

Featured Excerpt: Family of Spies

It began with a mysterious letter from a screenwriter, asking about a story. Your family. World War II. Nazi spies. It evolved into a thirty-year quest to discover the truth behind a horrendous family secret. Christine Kuehn’s Family of Spies is the never-before-told story of one family’s shocking involvement as Nazi and Japanese spies during WWII…

2025 Holiday Gift Guide

This December, we’re taking a look back at the many fascinating history books that published this year. From axe murderers to the history of rope, from the biography of Mt. Rushmore to a diverse array of WWII stories, the 2025 Holiday Gift Guide has a book recommendation for every history lover. Organized by general topic,…

Featured Excerpt: Progress

by Samuel Miller McDonald In Progress: How One Idea Built Civilization and Now Threatens to Destroy it, author Samuel Miller McDonald offers a bold, provocative, wide-ranging argument about the human idea of progress that offers a new vision of our future. Read on for a featured excerpt in which McDonald deconstructs a letter written by…

Featured Excerpt: Gemini

by Jeffrey Kluger Named by Time Magazine as one of the most anticipated books of fall 2025, Gemini by Jeffrey Kluger reveals the thrilling, untold story of the pioneering Gemini program that was instrumental in getting Americans on the moon. Read on for a featured, introductory excerpt! Like every man who had ever orbited the…

The Curious Case of Nuremberg’s Hangman

by Tim Queeney In his book Rope, author Tim Queeney takes readers on a unique and compelling adventure through the history of rope and its impact on civilization. In the article below, Queeney takes a look at the Nuremberg executions during WWII, which rope played a critical role in as the men were executed by…

Featured Excerpt: The Sea Captain’s Wife

by Tilar J. Mazzeo In The Sea Captain’s Wife, New York Times bestselling author Tilar J. Mazzeo reveals the true story of the first female captain of a merchant ship and her treacherous navigation of Antarctica’s deadly waters. Read on for a featured excerpt! Neptune’s Car Clipper Ship, 19th Century. Courtesy of Wikimedia. Public Domain….