Reading in Berkshire was founded around the 6th century AD by the Saxons, who had travelled up the rivers Thames and Kennett looking for a place to settle after travelling from areas of modern-day Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands. Over time, Reading grew from a small village to a prosperous market town. A view of…

Groundbreaking English Women of Science in History

Scientific discoveries and advancements have always shaped history, but many important contributions are still to be equally recognised. While people often talk about Sir Isaac Newton and Edward Jenner, the amazing work of many women in science over the centuries is less well-known. Here, we shine a light on their stories: women who made giant…

10 Historic Places to Explore in York

Founded by the Romans in AD 71 and later shaped by the Vikings and Normans, York’s cobbled streets, medieval architecture, brilliant museums, and ruined remains offer a unique glimpse into England’s past. A view looking north-east along Stonegate in York, Yorkshire, with York Minster in the background, taken around 1853. Source: Historic England. View image CC61/00025. 1….

The Buildings of Architect Watson Fothergill

During the Victorian era (1837 to 1901), several architects, including Watson Fothergill, made their mark on England’s quickly changing landscape. From 1870 to 1912, Fothergill (1841 to 1928) worked tirelessly on plans for over 100 buildings across Nottinghamshire, bringing his grand designs for houses, warehouses, churches, and beyond to fruition. 1 to 7 Castle Road,…

A History of Bradford in 10 Places

Known for once being the ‘wool capital of the world’, its UNESCO World Heritage Site in Saltaire, and its literary connections to the Brontë sisters, Bradford in West Yorkshire has a fascinating history. The Anglo-Saxons first established it as a small village known as ‘Broad Ford’ on a crossing over the Bradford Beck, a river…

What Was the Capital of England Before London?

London is England’s capital city. As the seat of government, the focus of many cultural institutions, and the centre of national and historic rituals, ‘the Big Smoke’ is a rather important place. But while London has had this role for a long time, it hasn’t always been the capital. Here, we explore the locations that…

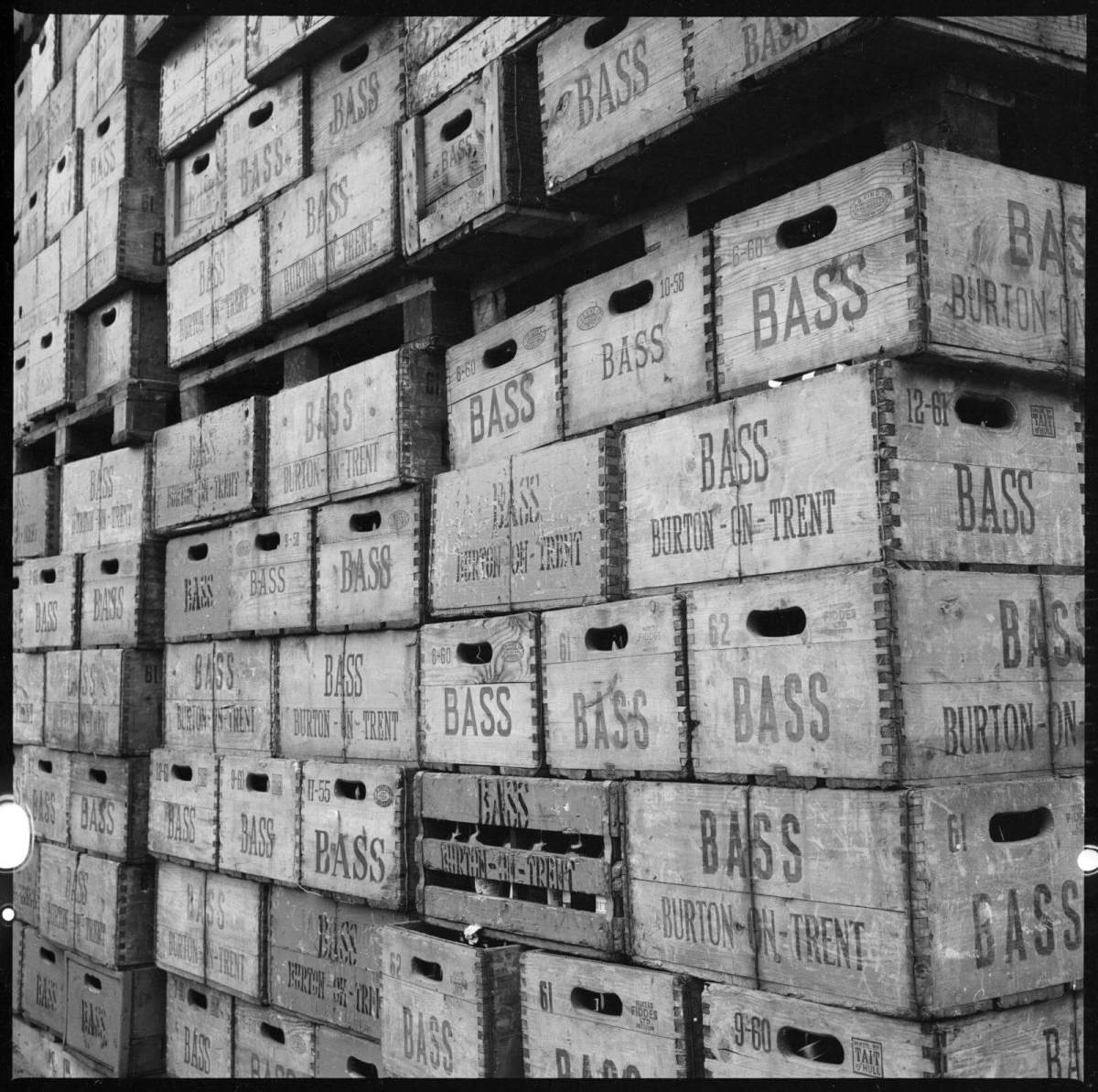

The Beer Capital of England

The brewing of ale and beer has a long history in England, but the town of Burton upon Trent in Staffordshire has a special relationship with the drink. By the end of the 19th century, Burton was home to the most extensive beer breweries in the world, with over half of the town’s working population employed…

The Tough-As-Nails, Openly Gay Ex-Miner

Tucked away on the corner of Vicar Road in Darfield, an ex-mining village in South Yorkshire, there’s an inconspicuous, volunteer-led museum containing a truly surprising history. Maurice Dobson Museum, Vicar Road, Darfield, South Yorkshire. © Historic England Archive. View image DP486503. View List entry 1151167. The Maurice Dobson Museum and Heritage Centre is billed as…

The Development of England’s Suburbs

Over the past 2 centuries, England’s towns and cities have experienced unparalleled growth, which has led to the creation of the suburbs on the edge of urban areas where most of us now live. Due to the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century and the need for more housing for a soaring population, suburban development…

A History of Stoke-on-Trent in 8 Places

In the 18th century, the ceramic industry was essential to industrial Britain’s development. Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire played a key role in the pottery industry for over 300 years, gaining its affectionate nickname ‘The Potteries’. Middleport Pottery, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, photographed in the 1960s. © Historic England Archive. View image DES01/04/0136. View List entry 1297939. The…