Can you define England without mentioning post boxes or telephone boxes? We are surrounded by historic designs and constructions that were initially invented for everyday purposes, such as to inform us where we were going, communicate with one another, or even drink water. A crinkle crankle wall on Scudamore Place, Ditchingham, Norfolk. © Historic England…

The History of the Railway in England

The world’s first standard gauge, steam-hauled public railway, the Stockton and Darlington, opened on 27 September 1825, connecting places, people, and communities. It went on to transform the world. A railway revolution swept Britain in the 19th century, changing the country forever. A predominantly agricultural society had metamorphosed into an urbanised industrial superpower. ‘The Opening…

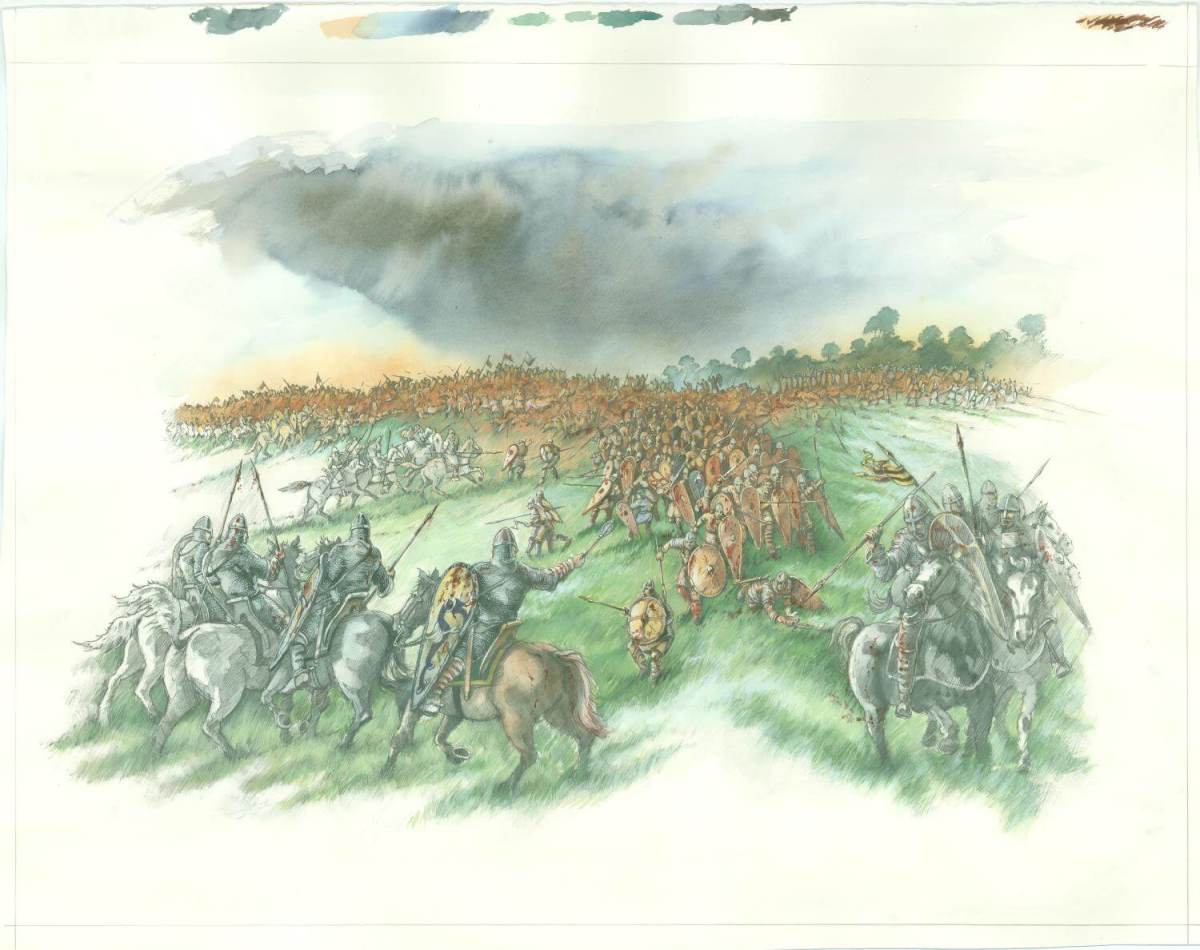

Exploring the Myths of the Wars of the Roses Battlefields

2025 sees the 30th anniversary of the establishment of Historic England’s Register of Historic Battlefields. It lists 47 English battlefields from the Battle of Maldon in AD 991 to the Battle of Sedgemoor in 1685. Eight battlefields from the intermittent period of civil war and rebellion between 1455 and 1487, known as the Wars of…

Discover England’s Hidden Prehistoric Monuments and Sites

Stonehenge has captured people’s imaginations for centuries as one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments. But England has hundreds of other ancient sites, each with its own story. These monuments, scattered across the landscape from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic periods, offer a glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and cultures of our prehistoric predecessors….

8 Historic Places Connected to Jane Austen

Jane Austen (1775 to 1817) is one of the most celebrated authors in English literature, renowned for her astute observations of early 19th-century British society, her wit and use of satire, and her strong female protagonists. A watercolour of author Jane Austen by James Andrews. © The History Collection / Alamy Stock Photo Her novels,…

Discover the Sea’s Influence on England’s Coastal Heritage

When you see the ocean, what do you see? The possibility of travel, food, and the endless blue? How do you feel? Calm, nervous, apprehensive? The sea has always played a significant role in the life of the inhabitants of the British Isles. We have traded on it, sailed it, surfed it, learnt from it…

Sophia Duleep Singh: Pioneering Suffragette and Activist

Sophia Duleep Singh (1876 to 1948) was a suffragette and prominent women’s rights campaigner in Great Britain. She was the daughter of Maharajah Duleep Singh, the last Sikh ruler of the Punjab, and the goddaughter of Queen Victoria. Princess Sophia Alexandra Duleep Singh, photographed in 1895. Source: Public domain. When was Sophia Duleep Singh born?…

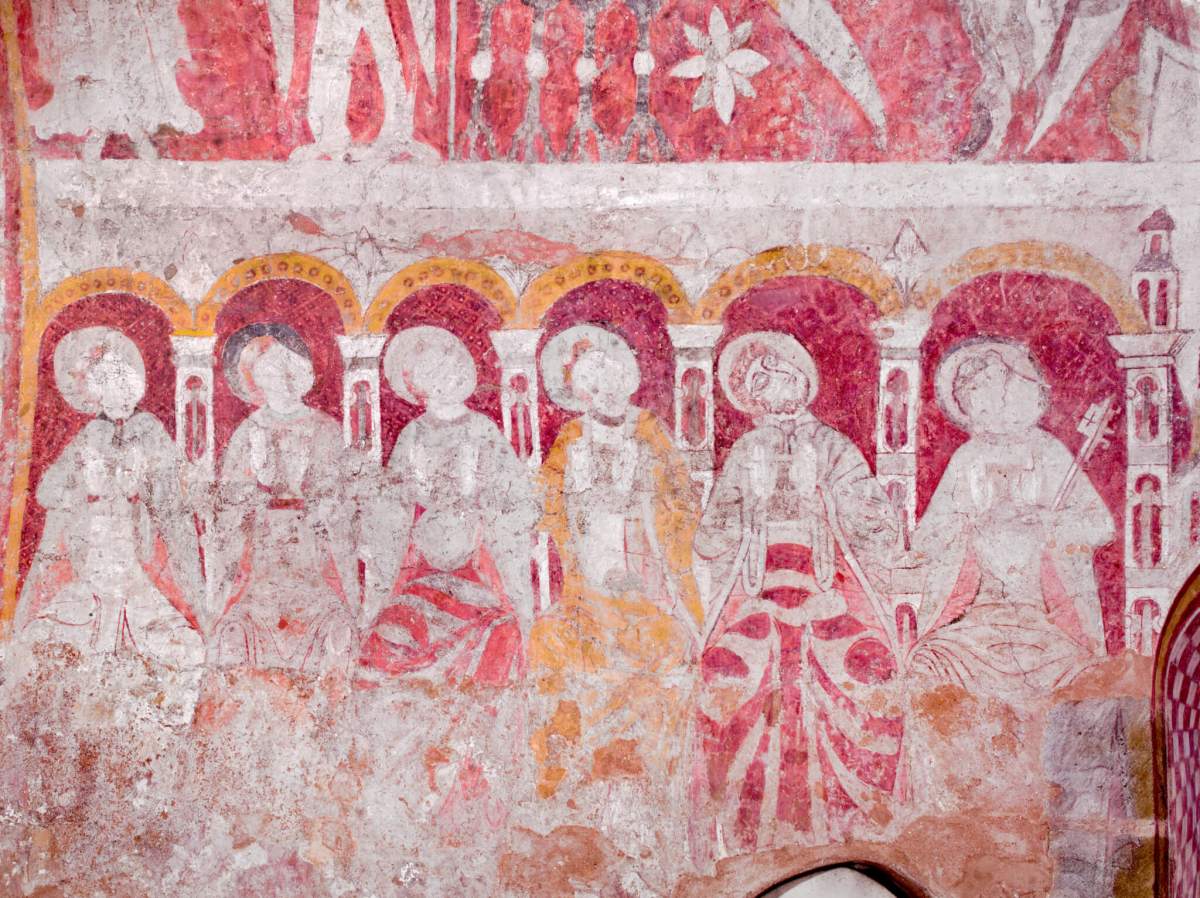

The Middle Ages to the Victorians

For centuries, England has had a rich tradition of decorating interior walls with painted imagery. The paintings could depict tales from the Bible and offer moral warnings to local church congregations, almost all of whom were unable to read or write before education became widely available. Wall paintings first appeared in England during the Roman…

Why he invaded England in 1066

William I, also known as William the Conqueror, was the first Norman king of England, who reigned from 1066 to 1087. Before this, he was the Duke of Normandy from 1035. When the Anglo-Saxon English king, Edward the Confessor, died in 1066, William set his sights on invading England and expanding his power. Invading England…

The History of Carnival in England

From the burning flames of effigies of Guy Fawkes, ignited and ashy annual reminders to keep in line or be immortalised into history as an enemy of Great Britannia, to the burning of sugared plantations in the Caribbean causing panicked uproars in British Parliament, flames and fury transforming itself into jubilant celebration is an evolution…