Lined with vibrant restaurants and bustling shops, Chinatowns are lively culinary hubs at the heart of England’s cities. A melting pot of diverse Asian cultures and communities, they are often marked by a distinctive Chinese archway, or paifang, which stands as a cultural symbol of Chinese heritage in England. Chinatown, Gerrard Street, London. © Historic…

The Pioneering Stockton and Darlington Railway

When the railway expanded in Britain in the 19th century, it transformed the way people lived, worked and socialised. Heavy goods could be transported faster than before, rural areas now had access to urban centres and new employment opportunities, and travel and leisure activities became more accessible for most people. But how and when did…

What Is the Oldest Pub in London?

There are many claimants for London’s oldest public house, with several names repeatedly cropping up. The earliest pubs were medieval alehouses, taverns, and inns. The term ‘public house’ was in use by the early 17th century and included these early types of buildings. No historic pubs survived the Great Fire of London in 1666, and…

A Brief Introduction to Martello Towers – The Historic England Blog

Martello towers are a series of small coastal artillery forts, built to counter the threat of invasion from France in the Napoleonic era (roughly 1799 to 1815). The name and form of the Martello tower derive from a small defensive tower at Punta Mortella, a point in the bay of San Fiorenzo in Corsica. The…

10 Historic Locations Featured in Classic British Horror Movies – The Historic England Blog

Scares on screen are as old as cinema itself. From the early years of horror film production in England to the present day, ghosts, haunted houses and other creepy subjects found a suitable outlet in the darkened space of the movie theatre. One obvious advantage to English filmmakers is that living in a country steeped in…

A Brief Introduction to Arts and Crafts Architecture – The Historic England Blog

The Arts and Crafts movement emerged in the late 19th century in reaction to the Industrial Revolution. It celebrated craftsmanship, local materials and functional design, positioning itself in contrast to the arrival of mass production and machine-made goods. William Morris and John Ruskin The Arts and Crafts movement was inspired by the ideas of writer…

Hostel, House, and Chambers – The Historic England Blog

In her guidebook from 1900, the journalist Dora Jones declared “The life of a bachelor girl in a big city [is] a wonderful and glorious vision … What a thing it must be…to be like Celia in London, who has a career, in music perhaps, or art or journalism, who lives in chambers like a…

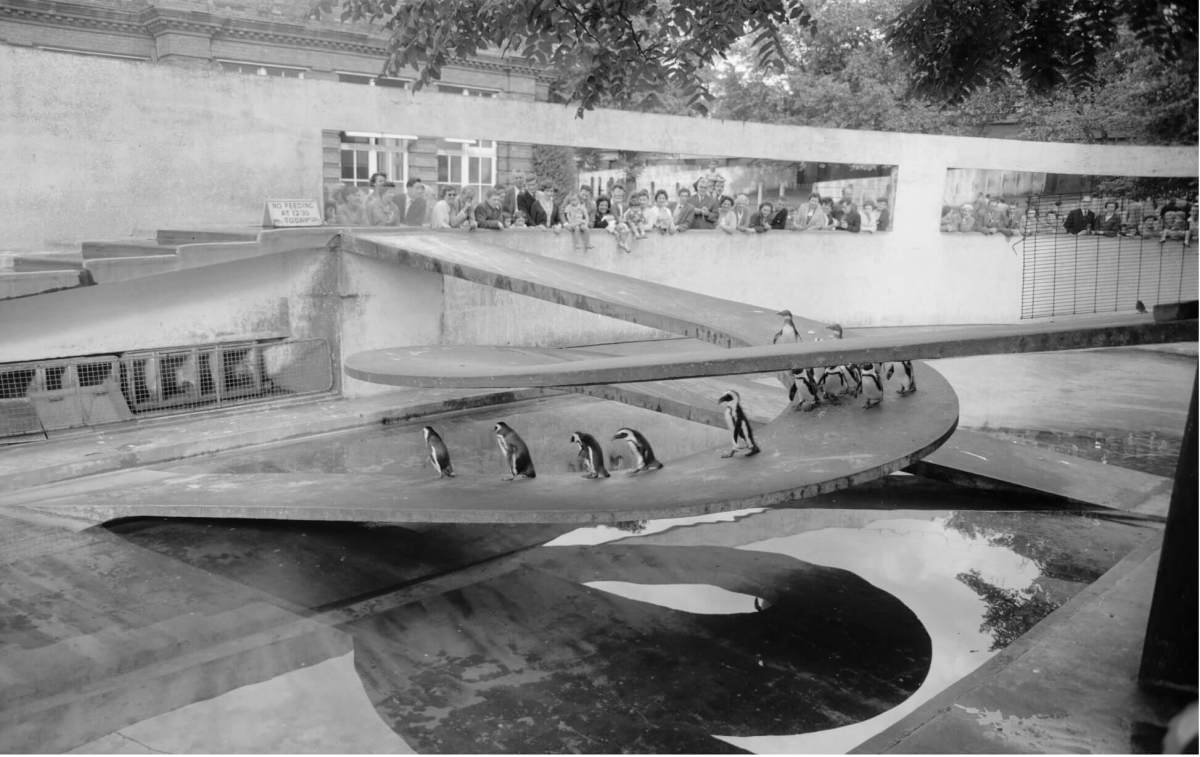

Lubetkin’s Works in England

Written by Nicky Hughes Berthold Lubetkin, who co-founded the radical 1930s architectural practice, Tecton, was a leading figure in the development of Modernist architecture in Britain. His architectural education coincided with the Russian Revolution in 1917 and he became immersed in the Constructivist movement, in which all the arts were brought together in the service…

The Works of Modernist Architect Eric Lyons

Span Developments was formally founded in 1957 by the architect Eric Lyons (1912-1980), the architect-developer Geoffrey Townsend (1911-2002) and the developer Leslie Bilsby. Their combination of expertise and enlightened property speculation was unusual at the time. Both Bilsby and Townsend, with whom Lyons had been an architectural student at the Regent Street Polytechnic, were keen…

Reusing Historic Cinemas as Places of Worship

Written by Dr Kate Jordan, Westminster University. Cinemas were once a familiar feature of every high street. At their peak in 1946, an astonishing 4,709 cinemas were operating in Britain’s towns and cities. These dynamic buildings offered respite from the gloom of depression, wartime and rationing, beckoning audiences not only to watch films but also…