In this blog post we’ll explore the hidden histories of listed pubs with a festive theme, selected by Amy and Caroline from Historic England’s Listing Policy Team. Pubs are often part of our festive celebrations, whether that’s a warming mulled wine after a busy day of gift shopping, or a work celebration with Christmas crackers…

Alsatian conscription evaders in Switzerland – Swiss National Museum

On the evening of 12 February 1943, the group congregated in the Alsatian town of Ballersdorf, before setting off on foot into the darkness at around 10 pm. Their aim was to cross the Swiss border – around 15 kilometres to the south as the crow flies – to avoid being forcibly conscripted to fight in…

Sabina Spielrein – a rediscovered voice of psychoanalysis – Swiss National Museum

Landscapes of the Soul. C.G. Jung and the exploration of the human psyche in Switzerland Switzerland has been home to a number of soul searchers over the years, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Friedrich Nietzsche and Carl Gustav Jung. Their work had a major impact on the development of psychiatry and psychoanalysis. To mark the 150th…

The right to privacy, except during wartime – Swiss National Museum

During times of political unrest – especially during the two world wars – state censors monitored private as well as military correspondence. They made no attempt to hide their actions. Nadja Ackermann is a scientific archivist responsible for company archives in the Burgerbibliothek Bern.

The bombing of the Sihl plain – Swiss National Museum

The first attempts involved buried bombs before dropping the high-explosive and finally firebombs. An illustrated report in weekly newspaper Zürcher Illustrierte contained a number of striking photographs demonstrating the effect of a high-explosive bomb, which fell about a metre from the building. The article said: “The detonation could be heard over 10 km away. It…

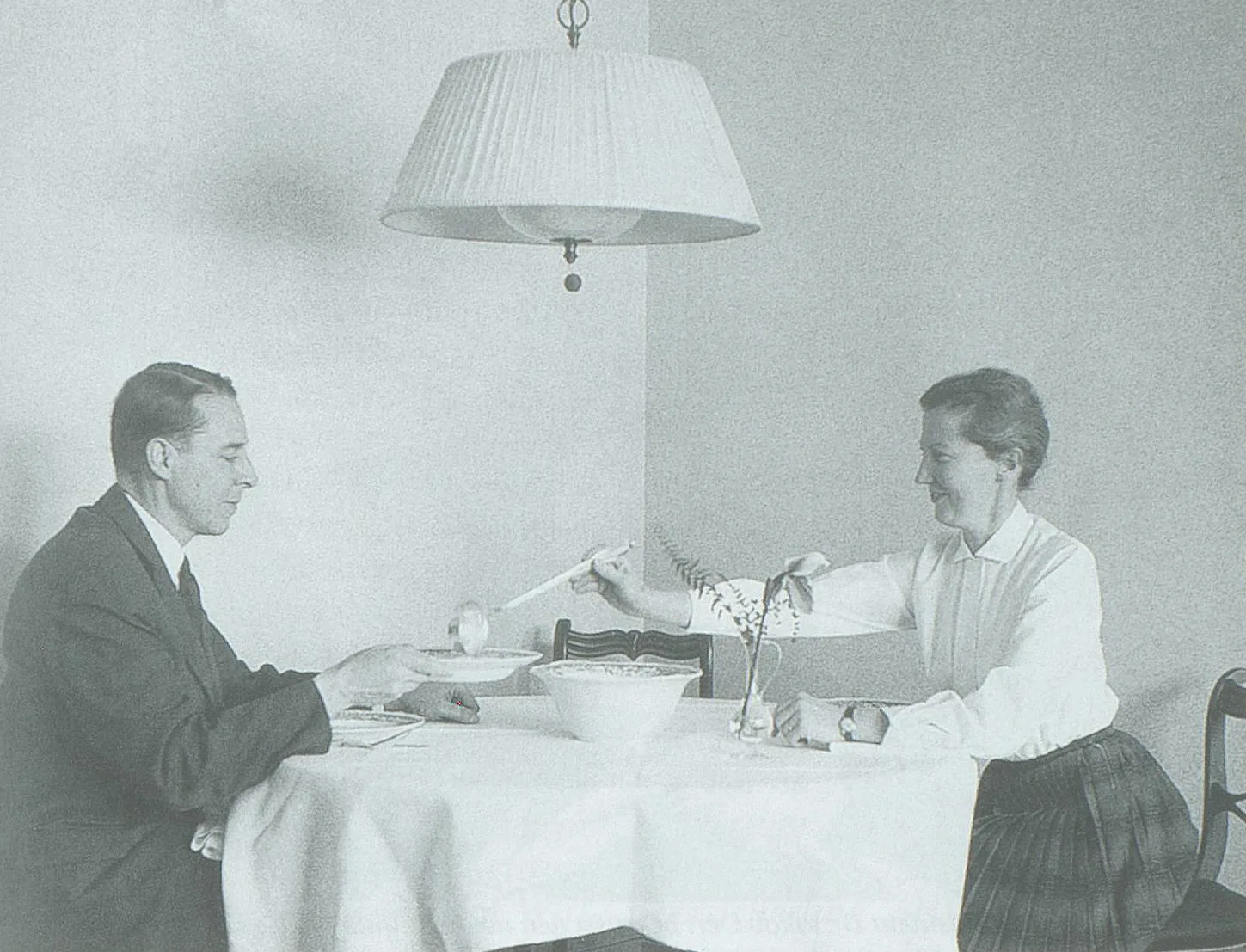

An extraordinarily successful couple – Swiss National Museum

Hans Peter Tschudi was proud of his wife, whom he had married in spring 1952, and of her success as a scientist: “Towards the end of my time at the Trade Inspectorate, I had the good fortune to meet Irma Steiner, Dr. med. et phil. nat., a qualified lecturer and assistant at the pharmaceutical institute…

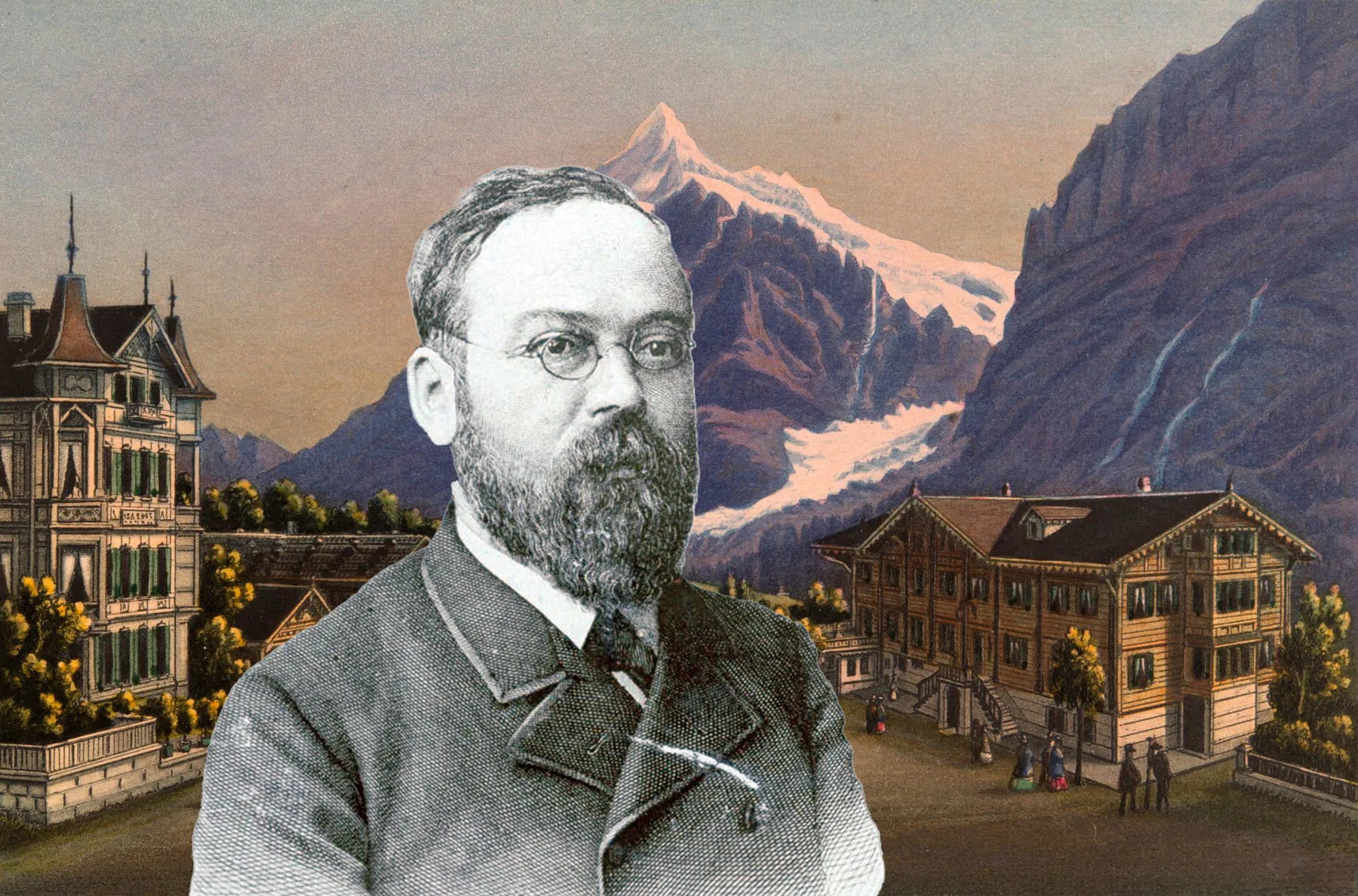

The ‘glacier pastor’ – Swiss National Museum

Gottfried Strasser was born on 12 March 1854 in Lauenen near Gstaad. His father Johannes, a clergyman, was married to Emilie Katharina Ludwig, whose father Emanuel had been a pastor at Bern Minster. The family moved to Langnau in the Emmental region in 1855. Gottfried grew up there, in a lively household of two sisters and…

Defending Switzerland against attacks that never happened – Swiss National Museum

In the early 19th century, Switzerland was traumatised by the French invasion of 1798 and there were fears that France would attack again. In Switzerland’s defence planning, Aarberg was a strategic military location as French armies could potentially cross the River Aare there. An obstacle was therefore needed. Dr. phil., Curator of the Information and…

Where was Jesus born? – Swiss National Museum

The setting in which Jesus actually came into the world remains a mystery – but the way it has been imagined has shaped Christian Christmas culture for centuries. In art and crib building, the nativity scene has been depicted in various locations, including a stable, a cave, a ruin, and a house, in each case…

Hammer and sickle on the Gotthard

Medievalist Marcel Beck kept a diary throughout his military service. It reveals a different, rarely seen side of active service during the Second World War.